By JOHN RUGGIERI

In the museum retrospective of Rudolf Stingel, the quiet drama in his work is heightened by scale and context.

The art world has been wrestling with the idea that “Painting is dead” for quite some time. Some artists have succeeded by redefining painting as a radically sculptural medium. In Stingel’s smartly installed twenty-year survey, we are given a bounty of painting and some non-painted products of what we are told are Stingel’s wrestling with just a teensy little topic – “painting’s validity” – by richly injecting his self, footsteps, studio space, and photorealistic image into the work through divergent styles.

“For Stingel,” according to Gary Carrion-Murayari, assistant curator at the Whitney, “operating at the border of where painting dissolves into sculpture, architecture, and the everyday is the best way to continually renew his practice and assert the vitality of painting as a critical medium.”

Stingel is all too aware of the historical power and powerlessness of painting as a medium and knows that his juggling of multiple mediums and visual tricks keeps the act of painting alive for him and for those open to eclecticism. He mixes monochromatic spectacle, the union of art and design, and the quieter craft of oil painting, both challenging the traditionalists hell-bent on representation as the ultimate art form and the more painting-jaded among us.

One solution for Stingel to making painting relevant is to create indoor public art out of it. He is widely known for his Plan B, a sweetly anarchic project that installed wall-to-wall pink and blue carpet in Grand Central Terminal’s Vanderbilt Hall for a month. In another more “public” way, he has published the steps involved in making his silvery blue, red, gold paintings in his Instructions – through the more private mode of limited edition.

The first exhibition hall, lit by a great chandelier in the cavernous space, is a big, silver, and shiny room paneled in a high-end, reflective foil wallpaper. The tall walls have been marked up from floor to ceiling by a multitude of viewers, who have been invited to carve, doodle, and message their “democratic and viral” way into Stingel’s exhibition while installed previously in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA) and currently at the Whitney.

His silver room installation is the end result after responding to how visitors would carve into the metallic surface of his paintings in past exhibitions. While I might be more inclined to call the authorities, Stingel used this prod to develop his silver room for all those with a tendency toward self-expression when inside exhibition halls.

I flew through it on my way to the meat of more finished, artist-made works – what Carrion-Murayari would call the work of “one privileged individual” – trying to persuade myself that his good intentions make for an important bridge between the art world and an expressive audience, a real-life MySpace. I am still persuading myself of this.

His idea of spectacle is less colorful than in previous colored-carpeting installations but still effective at the Whitney in the silver room, the mirrored floor, and the cheeky daring of exhibiting his “Oops there it is” low-pile rug from his studio and walked-in Styrofoam. One gallery was hung with dark baroque-patterned paintings reflected in the floor installed with a mirrored surface – dizzying, voyeuristic, glamorous, and slightly fun. I had a vertigo-like experience, similar to the visual cacophony, and eventual headache, of staring at the Op Art of a Bridget Riley painting, a Liz Deschenes Registration photograph, or the Flash design of Dimitry Chamy.

A series of thick Styrofoam wall works crushed in a random path pattern by the artist’s bootprints, pre-soaked in acid or lacquer thinner, surprisingly drew me into it due to its snow-like form and placement on the wall. These pieces had shades of the earlier conceptualist Joseph Beuys’s near-death experience when his combat bomber plane crashed in the snowy Crimean Front in 1944 and was warmed back to life by natives with felt and fat, later his own innovative art materials.

It’s simply not easy to be innovative with materials in “painting,” for lack of a better word here, and my first reaction was to write the use of Styrofoam off as a shock-art technique. So much has been done already. Stingel’s self is not only present here in the crushed panels, but in all of this work he is conscious of being self-conscious about art history and he exploits that and turns it into intelligence.

He is neither a dilettante trying out different materials for effect or a shock artist. Stingel’s “style” is to be inclusive, in a decisive manner, and he bridges design and home décor with conceptual art with a celebratory flourish, and maybe a smirk, not so much a tongue in cheek.

One huge wall covered by a beige, neatly paint-smeared carpeting harvested from the floor of Stingel’s studio did not engage me. With this taupe wall installation, he appears to be following the well-received earlier exhibitions of vibrantly colored carpeting, which were sometimes interactive and much more of a spectacle. The concept of bringing the familiar, mundane world into the gallery needs to be heightened here. This work doesn’t ring as visually and conceptually interesting as the Styrofoam pieces and fell flat on the wall as mere ironic gesture.

The inclusion by the artist and curators of a cast radiator sculpture too obviously reminiscent of a Jessica Whiteread object was puzzling. I am sure Stingel knows of her work and may have been simply using, even borrowing, a similar technique. Its interior-ness may “go” with the wall of studio carpeting, but it seemed to be something added for effect, too intent on being another part of the exhibition “décor.” His trampled Styrofoam isn’t art or risk-taking for its own sake, but thoughtful and deliberate jabs at conventional ideas of craftsmanship, artistic technique, and authorship.

There is something potentially anarchic in the visually manic art of the 60’s here, but I find power in work of a hushed tone, especially as a card-carrying product of our more conservative, freedom-loving yet franchised culture.

For those who might flinch and guffaw at ol’ Modern Art in Stingel’s Styrofoam, his retrospective also includes finely crafted self-portraits, works he intends not necessarily to please the audience but perhaps to jiggle our conventional notion that an artist must have a consistent style.

Critic Jerry Salz has written that Stingel’s representational “painting is implicitly critical of other contemporary Photorealist painters; essentially it says, ‘Look how easy this kind of painting is.’ ” Stingel thumbs his brush at those traditionalists who are blinded to the notion of eclectic art practice and perhaps even the craftsmanship of abstraction.

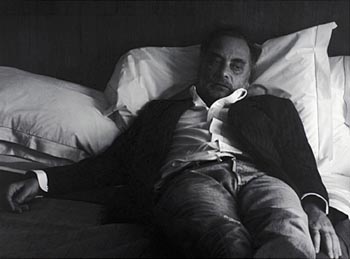

I ended my Stingel tour in a room of a suite of a few mammoth, photorealistic paintings of the artist himself – taken from images created with a photographer – installed in a room with equally large, blackish, decoratively patterned paintings. To enlarge his own image to upwards of 132 by 180 inches in the male odalisque Untitled (After Sam), previously exhibited in the 2006 Whitney Biennial, could be easily seen as a narcissistic will to power. I had guesstimated the size of these paintings as up to fifty feet to others before looking it up. The enlargement of this intimate, though depressed image of Stingel and its rich mass of darkness made the paintings seem much larger than their actual dimensions.

These are giant, intensely dark self-portraits, with somber Stingel in a posh pinstripe suit jacket sprawled on a bed fitted with what must be high-thread count bedding, almost literally gazing at his navel. But like so many of the best portraits of artists, Stingel’s self-images – Untitled (After Sam) is literally a layout – are direct and indulgent without the vanity that an accomplished man of fifty may usually wish to project. He is well-dressed but unsmiling, posed but perhaps more honest than the user-friendly images of other creative elders, such as Ralph Lauren, who must guard their warm, friendly brand as part of the fashion game.

The Whitney’s press release states that the canvases mysteriously “show a dark, melancholic side of the state of mind of the Western artist,” and perhaps it is the artist’s European roots that allow him to reveal a more sober image. Stingel’s self-portraits apparently picture a man on the precipitous edges of mid-life in a momentary creative downer, even a tad vulnerable, but the forlorn prince of participatory art is too savvy to appear tortured.

The self-portraits’ delicately webbed daubs of black and grey tones have a Germanic detachment and stylization, as executed by the artist and his assistants. These are indeed wealthy paintings, rich with mood and the same kind of painterly goodness found in Chuck Close’s portraits, especially close up. Stingel’s indulgence becomes our indulgence, allowing us an immense space at the Whitney to shrug, slump, and feel our own existential darkness, perhaps the blacks and grays hidden when we looking at our shiny reflections and not our murky insides.

- Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (After Sam), oil on canvas, 2005-2006

- Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, Styrofoam, 2000.

- Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, foil covered foam, 2001-2002, Photo by Sheldon C. Collins.

"Rudolf Stingel" is on view until October 14th at the Whitney Museum of American Art, located at 945 Madison Ave., New York.

All images are courtesy of the artist, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Paula Cooper Gallery.