The scratch and sniff walls are gone, along with the trippy hallway, though the Star Wars helmets and 2001: A Space Odyssey set reproduction still occupy the entrance to Part II of theList Visual Art Center’s Sensorium: Embodied Experience, Technology, and Contemporary Art show despite the helmets’ electronics not always functioning correctly [1].

With the second half of the sensorially founded show, most of the works still rely largely on visual elements, which that in some ways belies the show’s intents. However, Part II incorporates the additional sense of taste into the spectrum of Sensorium with architect François Roche’s Mi(pi) Bar (2007), while sensing, as a cognitional act in general, is considered in Christian Jankowski’s Let's Get Physical/Digital (1997).

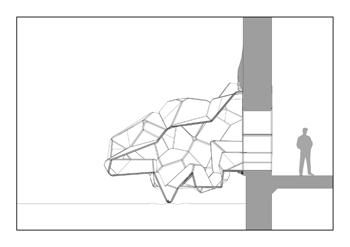

François Roche’s architectural firm, R&Sie (n), designed the Mi(pi) Bar as vestibule that they wished to resemble a “physical secretion” from I.M. Pei’s Wiesner Building where the List resides. The architectural “secretion” is aesthetically related to the Wiesner building in an analogous way to humans and their own liquid excrement: The vestibule lacks any symmetry (the Wiesner is a large cube, for the most part), but is completely white and appears geometric, giving it a structural congruence to the Wiesner. Its position and shape make it appear to be crystalline waste growing from the side of the building. Inside the vestibule, the analogy carries through with an apparatus for making tea from urine. We are supposed to think it’s gross, or have a “phobic response,” to the idea of drinking our own pee, however, the piece is seeking to subvert common beliefs about urine as a waste product from the body and promote ideals of sustainability. The piece itself which resides in the gallery space, is comprised mostly of text that politely patronizes the reader in a way similar to that of a high-school science teacher on the misunderstandings about urine and renal physiology.

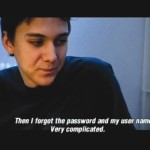

Christian Jankowski’s Let's Get Physical/Digital is a social experiment on internet based “chat.” In 1997, when his and his girlfriend’s lives necessitated that they reside in different countries, they used chat rooms to stay in touch. Jankowski saved their dialogues and then recruited actors, by way of meeting them in chat rooms, to act out the dialogues which he videotaped. The information—Jankowski and his girlfriend’s dialogue—passes through several mediums (chat room, script, spoken language, video, and finally—translation in the form of subtitles) before the viewer experiences it, creating a final piece that is both funny and touching at times. The dialogue, because it originally relied on typed words alone, has a certain desperation and deliberateness as Jankowski and his girlfriend needed to maximize the meaning every clunky packet of bits sent between them.

According the show’s literature, "less than five percent of the sensorial information" human's use to communicate is actually transmitted in chat room conversations. These "'low bandwidth encounters,'" as cultural theorists like to refer to them, have given birth to new forms of web communication, which increase the efficiency of cyber interaction, in the form of 'emoticons' and 'pictocons.' These attempts to increase the "bandwidth" of sensorial information (think Me and You and Everyone We Know) are at the same time decreasing the ability of people to provide their own effective prose.

This desegregation of verbal and visual language touches upon the show’s main point of how technology is changing the way humans experience the post-modern world. An impetus for the show was MIT professor Caroline A. Jones’s Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg's Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses (University of Chicago Press 2006). According to Jones, among others, Greenberg’s theories were a response to the paradigm which he inhabited. His theories weren’t rigorously founded upon the work of other theorists (e.g. Kant), and were more or less "developed in relation to the rationalized procedures that gained wide currency in the United States at midcentury, in fields ranging from the sense-data protocols theorized by scientific philosophy to the development of cultural forms, such as hi-fi, that targeted specific senses, one by one." [2]

In my opinion, the majority of art is visual because of evolutionary reasons. Even despite any "bureaucratization," vision is our most dominant sense: if we were bats or rabbits, it would be more auditory, if we were bloodhounds or moles, it would be more olfactory. How ever relevant Jones's theories are or whether they can be proven, they do serve as a launch pad for the exploration of how our consciousness is changing with the advent of new ways to see and communicate with the world. As mediums were indeed segmented per sense in modern art, the curators of Sensorium took a close look at works which “transposed” media or senses, or had synaesthetic properties such as Natascha Sadr Haghighian’s placing of a speaker into the eyepiece of a microscope in Singing Microscope, or Sissel Tolaas "painting" with body odor in Sensorium, Part I.

It is the institutionalization and taxonomy of knowledge and the hierarchies that they bring about that interests Haghighian, even to the extent of creating a new platform for the exchange of biographical information (e.g. CV's and biographies) for the web, bioswop.net. After reading MIT Professor of History and Philosophy of Science Evelyn Fox-Keller's work, most notably The Biological Gaze, which looks specifically at the Microscope, Haghighian made Singing Microscope. Though the piece may be an important and nuanced study of the ways gender influences scientific discovery, it's not an easy fit in Sensorium. Unfortunately, there is little the viewer can glean from a microscope with a speaker for an eyepiece in terms of its sensorial transposition, and the audio emitting from said speaker is so nearly unintelligible as to not provide the "information" required to understand the piece. To make matters worse for Haghighian, the wall text, "The standard practice of eye to eyepiece will instantiate the frustration of "seeing nothing" as viewers swap ear for eye and hearing for vision, and discover a soundtrack in place of visual information." makes her piece seem like a one-liner and seems to be struggling to bring her piece the same significance and profundity as the other works in the show.

The Albanian artist Anri Sala's NaturalMystic (Tomahawk #2) (2002) works well to heighten the auditory qualities of the work; the fact that it is video becomes an afterthought. The silent room; simple, subject-center cinematography; and high-fidelity head-phones allow the viewer to easily imagine the war experience of the musician on screen who imitates the sounds of a tomahawk missile flying above then hitting its target off in the distance. The musician’s voice reminded me of an elderly relative telling a war story when I was a child: the instance of a person mimicking the sound of a bomb became just as horrifying as the real thing may have been to them during the actual war. In this case, the musician in the video, who may very well have experienced the sounds of bombing during one of the many recent Balkan conflicts, becomes that story teller. However, the piece takes itself so seriously it’s a bit campy. Would it hurt to allow the subject a little more subjectivity? Tell us a little more about this guy so the piece doesn’t risk coming off as pretentious pseudo-documentary.

In Now I See (2004), a nine minute 35mm film, the profound understanding the artist sought to bring about never succeeds beyond the initial concept and gets lost in an execution which lacks certain coherence. In what is essentially a music video not dissimilar from Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit," the Icelandic band, Trabant, perform in a dark rock&roll concert venue replete with strobe lighting. Part way through the performance, the camera begins to follow around balloon dog that which seems to levitate in the middle of the stage. Through some filmic trickery, time and space collapse (as they usually do in film and video) and the balloon dog seems to float into empty space then back into the concert. Similar to R&Sie (n)'s Mi(pi) Bar, Now I See is a science experiment, though formally much less. In the context of a show seeking to highlight artworks' transpositive properties of different mediums, the balloon dog is simply moving through the air via the sound waves from the rock band’s speakers. And like Mi(pi) Bar, it is likenable to a high school science teacher’s way of invading his brain dead students’ psyches. The piece compensates with the loudness and size of the space which it was given as the experience is enveloping and cinematic. But this only makes the concept in terms of Sensorium easy to miss.

If given a wider context than art, would the show be more interesting? It is a fascinating show with a lot of thoughtful work, but the impetus for the show, Caroline A. Jones’s Eyesight Alone and that technology is changing sensorial experience, could have driven the show further, giving it a wider context. It may only be in the space of a gallery where such cultural explorations may first make their mark, but art is the not only cultural phenomenon grappling with this issue. To be fair, the show encompassed a wide array of mediums, however, what I remember is the audio-visual experience, and the funny smelling walls.

- R&Sie (n), MI(pi) bar, 2007. Courtesy the agency.

- Christian Jankowski, Let’s Get Physical/Digital, Video, 1997. Courtesy the artist and Maccorone Inc, New York.

- Anri Sala, Naturalmystic (Tomahawk #2), Video, 2002. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Zürich London; Johnen Schöttle, Berlin, Cologne, Munich; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.

----

[1] - If you’re going to be in Paris anytime soon, the Gallerie Maisonneuve will be showing the work, and the helmets should be in full effect.

[2] - From the University of Chicago Press website for Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg's Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses by Caroline A. Jones.

"Sensorium: Embodied Experience, Technology, and Contemporary Art, Part II" is on view until April 8, 2007 at MIT's List Visual Art Center.