MARKETWATCH

As exciting as this is, imagine how exciting the collapse is going to be!

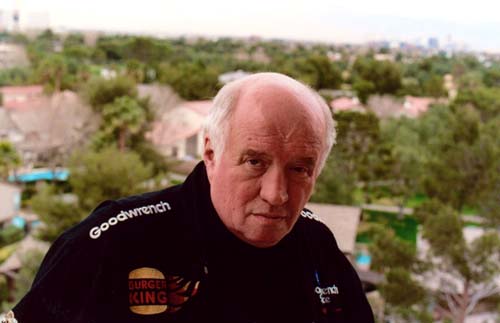

The above quote turned out to be a bit of a prelude. Speaking at the Frieze art fair well before the economic meltdown in 2008, Dave Hickey appeared almost anxious for the inevitable art bubble collapse. I re-listened to his lecture recently because I recalled Mr. Hickey mention how “honesty” and “values” might return to the art world. And how this might be a trend? Really? Indeed, Hickey speaks quite convincingly on what values he thinks might be resurfacing.

The crux of Hickey’s outlook rests on the desire for dealers to return to what he calls primary practice. Which is to say, they do something radical and only show art they like. In the old days of art commerce (which is to say pre 1970), artists would work in the studio, bring their art to a gallery and the dealer would in turn sell it. Critics and art historians would subsequently write about what they were willing to stake their reputations on, just as dealers were pledging their credibility on the art they were selling. Respectable people with different investments in the market, not to mention different opinions about the work, could still create a concensus about the art circulating in any particular region. Museums then acted as representatives of their communities by exhibiting the work these diverse people stood behind. This means whatever the museum exhibits would represent the values of the community and thus epitomize its values, no matter how unattractive that may be.

The deviation from this loose format makes it more difficult to see the art a particular community believes in, or at least has participated with. In Portland, OR, the Jubitz Center for Modern & Contemporary Art is the primary attraction for visitors to the Portland Art Musuem wanting to see Modern works. The exhibitions, however, are rarely from or about Portland. In general, the art has never been exhibited in the region, but has recently been bought and on loan from the Eli Broad trust. While I have no problem with Rachel Whiteread, Kehinde Wiley, Damien Hirst, or Jonathan Lasker, I simply don’t believe their work reflects the values of the city. In short, when a visitor comes to the Portland Art Musuem expecting to see our most distinguished artists, they will have trouble finding them. Instead, they will be greeted with the same work they just saw in NYC or LA. (To be fair, PAM also has the Apex Series, which is dedicated to Northwest art. However, it is not nearly as prominent, nor as publicsized).

Private enchantment to public support means museums listen to the people in their community. They pay attention to the opinions of critics, bloggers, art historians, collectors and people whose job it is to discern value. Each of these people represent a separate price point for a work of art. However, real value is only accumulated when each party acts upon their unique interests, and their interests alone. Dealers represent artists they like, critics honestly critique works on display without conflict of interest, and most importantly, artists make the work they want to make, unhindered by who is paying for it. Simply stated, when these independent contractors, all of whom carry distinct agendas and opinions, agree on something, it accumulates real value in the art.

This, of course, runs contrary to the speculative market we have seen in the last several decades. A speculative market that most dealers have tried to accommodate by having a bit of everything. The rosters of most major galleries convey politically correct diversity, yet paradoxically, lack distinction, if only because so many of the other galleries parody the same predicament. One installation artist, one bad boy painter, one Middle Eastern video artist, one conceptual box maker, One German photographer, etc. As Mr. Hickey states, “You’ve got to show one of each.” Perhaps part of this dilemma originates with galleries trying to reflect the diversity of a community, a job better left to museums; or worse, are simply trying to cater to the largest number of collectors they can.

As the economy begins to show signs of life, Jerry Saltz continues to spew about the rebirth of art, New York auction houses stop guaranteed pay outs, collectors begin to feel buyers remorse, Chelsea galleries close while others expand and paychecks to struggling artists begin to feel even further away, perhaps now, we can look at what we actually like, and stand behind it.

- Dave Hickey, photo Libby Lumpkin, found with google image search.