This is not a new discussion. However, because it usually takes place within the familiar boundaries of museums, galleries, and art academia, it rarely transcends its origin of specialized influence to elicit genuine participation from other disciplines of inquiry. When presented within art institutions to art audiences, activist art speaks quietly. Typically, gallery- and museum-goers are attuned to art history and criticism, and think about the relevance or success of an artwork’s message based on elements such as the artist’s point of view, attention to craft, process of fabrication, and the use of information signifiers that point to an idea, attitude or emotion. Viewed through such lenses, the direct, immediate cause for activism is often diffused.

What struck me about the article was that Temporary Services seemed genuinely committed to questioning the ways in which socially activist ideas are seen, heard, and experienced within artistic practice. Since I was in Chicago for the summer, I decided to contact Temporary Services and see if we could meet.

Over dinner at the Chicago Diner, Marc Fischer and Salem Collo-Julin, members of the group, introduced me to their most recent project: a book called “Prisoners Inventions” featuring the writings and drawings of Angelo. The book is partly a result of an on-going correspondence between Temporary Services and Angelo, first sparked by Angelo’s interest in one of Marc Fischer’s self-published zines over ten years ago. A prisoner in California, Angelo writes of his life in prison by describing his impressions, daily activities, and the physical cell that he lives in. His drawings illustrate inventions or problem solving solutions to living under constant supervision on a daily basis. In book form, the reader is able to internalize Angelo’s experience and identify with him as a fellow human being with practical needs, a desire to express himself through writing and art, as well as to personalize and organize his living space. Angelo’s drawings illustrate inventions in situations where resources are limited and time is immeasurable. The reader can reflect on the system of incarceration and what that necessitates, while recognizing the inherent relevance of the object as it pertains to an actual person’s experience. Serving as a starting point for investigation and inquiry into the penal system, “Prisoners’ Inventions” also addresses issues concerning the role of expression and freedom of speech.

Later that week, Marc and I found ourselves in a conversation about Prisoners’ Inventions with Aron Fischer (no relation to Marc), who was working as a public defender. As an advocate for defendants in the criminal justice system, Aron was interested in the way the project depicted the full humanity of prisoners, as opposed to the narrower legal or political claims he was used to making on their behalf. Marc, in turn, welcomed the chance to discuss the political implications of the work with someone in that world. For my part, I saw this as an opportunity to engage the idea of “Prisoners’ Inventions” in a manner that looks beyond the project’s identity as an art object, showcased within an art venue. At the end of the evening, we all felt there was more to say and decided to continue the conversation in written form.

The following is a dialogue between Jennifer Schmidt, Aron Fischer, and Temporary Services. It addresses the legal implications associated with “Prisoners’ Inventions” and Angelo, as well as the display of Prisoners’ Inventions as part of the Fantastic exhibition at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams, MA.

TS: One thing that came up as we were preparing for the exhibition of Prisoners’ Inventions at MASS MoCA, was a debate about the issue of morality when working with incarcerated persons. We do not know what Angelo was convicted of. He has requested that we, and the people we work with, respect his privacy by not pursuing the matter. Nonetheless, people commonly ask us why Angelo is incarcerated and how we could work with someone without having that knowledge. Thus far, Angelo has not asked us to participate in his legal situation. We work with Angelo because we value his art and ideas. He does not use his art to glorify or advance criminality in any way that could harm others and he has been terrifically generous with us.

Originally we planned to put Angelo’s full name on the project but the museum feared that they might be scandalized if someone researched Angelo’s conviction and made it public. They loved the project but were concerned about the risks. To eliminate that concern, Angelo suggested that we either make him anonymous or use his ‘artist name’ (Angelo) rather than his full name. So, in order to protect his privacy, we no longer use Angelo’s full name and we never mention what prison he is in. He clearly likes that his creative work is finding an audience, but as long as he is incarcerated, he just wants to “stay sane” while serving his time. He’s not interested in becoming a celebrity prisoner. Perhaps his work on this project will be personally helpful to him later in life if he gets paroled, but for now, the public dispersal of his work seems to be reward enough. He really enjoys seeing his drawings and writings exhibited and published.

Where we’re heading with this is the question of: how can prisoners usefully participate in the world in spite of their convictions and the moral judgments that many might make against them? We don’t think prisoners should have to wait until they get out to be productive. We know that prisoners already participate in our culture in various ways: they do work for industries that use prison labor: they make our street signs and license plates, they package Starbucks coffee and they do telemarketing. And then of course, prisoners also participate in our culture through all of the prison slang, fashions, and customs that we see on TV and in movies. Many people in the world of Hip Hop know about prison firsthand; James Brown learned to sing in prison.

One thing we are trying to work with in Prisoners’ Inventions is: how can prisoners’ channel their experiences of incarceration into constructive cultural work? How can prisoners make positive thoughtful contributions to culture in spite of their crimes? What kind of barriers do we have to contend with in order to get their work out into the world? So Aron, what can you add here? What are your thoughts on this from the legal work that you are doing?

AF: What interests me about “Prisoners’ Inventions” is that it’s by and about a prisoner, it’s about prison, but it doesn’t take any of the conventional positions on crime and punishment. In my world, whenever people talk about crime and punishment, it’s usually from one of a few well-staked-out points of view. One view is that crime is the result of racism, inequality, poverty, and so forth, not immorality. It follows from this that punishment shouldn’t be about revenge, it should be about rehabilitation, and maybe public safety. Another view is that crime is immoral, so criminals deserve to suffer; punishment should be about retribution. Then there are people who think punishment should be about deterring people from committing further crimes. Of course, elements of these viewpoints can be mixed and matched.

All of these positions share two things in common. First, they are very general—they are rarely based on careful attention to actual experiences of actual people. And second, they all assume that crime and punishment are inextricably linked; what you think about crime determines what you think about punishment, and vice-versa.

“Prisoners’ Inventions” is different. It is, as you say, a serious research project by a person with a lot of experience with what it’s like to be a prisoner. And Angelo says a lot about punishment—about prison—but refuses to talk about his crime. The effect of bucking convention in these ways is to suggest a much more humanistic way of thinking about prison than you see elsewhere. The viewer is not allowed to think about punishment in the abstract, apart from how it actually feels. The viewer is not allowed to let their ideas about crime color their ideas about how punishment feels.

Still, it’s inevitable that questions are going to arise about the politics of the thing. And it makes sense that those questions are directed at you guys rather than Angelo. Angelo can legitimately say that he’s just writing and drawing about his life, about what he knows. You say, you work with Angelo because you value his art and ideas, but, unlike Angelo, you chose to work with these ideas over many other ones. Why? Obviously, your work deals with the place of prison and prisoners in our culture. What are you saying about it?

I’m not saying you have to answer all those questions. But if you do—and it sounds to me like you’re trying to answer those questions when you talk about the contributions other prisoners can make to society—then I think it will be hard to avoid the questions of crime. When it’s just Angelo, it’s his decision not to talk about his crime, and he’s not trying to glorify or advance crime, and you respect that, and the viewer respects that. But if it’s not just Angelo, and if you’re also talking about other prisoners—about how maybe there are too many of them, or maybe more can be done to coordinate their participation in our culture—then why? Why do we want prisoners to participate? Why do they deserve it?

I guess you could just say, there are so many people incarcerated in the United States, many of them have something valuable to say, and, as long as what they have to say doesn’t glorify crime, everyone benefits from their saying it. And that works for people like Angelo, who can do their work sitting on their bunks with ballpoint pens. Legally, prisoners have a constitutional right to freedom of speech as long as the guards don’t have a good reason to take it away from them. But what about those who can’t make a contribution with nothing more than a ballpoint pen? Should conditions be changed to allow them to? Will that cost money? Will it make it easier for them to escape? Will it make prison too pleasant?

TS: We chose to work on this project – to ask Angelo about this material and to produce a book and exhibition – because of how compelling the material is. It really has a broad appeal and its importance was clear to us immediately. We seek out intense creativity wherever it resides. The art world is a place where you would expect to find a lot of creativity, but is probably the one field where it exists the least. For example, the biotech industry has harbored a frightening amount of creativity and experimentation – more than the art world has ever seen. The inventiveness and resourcefulness in the prisoners’ inventions offers several profound lessons to those of us not in prison.

Anyone can immediately see what an impoverished environment prisoners live in when they are presented with this material. In addition, the way that this project has been handled short-circuits the desire that a lot of people have for an “emotional target” – someplace to level blame and to justify or dismiss the horrendous circumstances under which we warehouse prisoners. The conditions most prisoners live with are appalling if not clearly human rights violations. We know that things don’t have to be this way. Prisons can be built in a way that minimizes exploitation, physical violence, sexual assault and related deadly diseases, recidivism and other problems that contemporary prison design compounds. Our culture is a selfish one and won’t spend the money or devote the resources necessary to seriously reduce crime and to rehabilitate those that can be. The biggest evidence of this is the privatization of prisons and that people will seek to increase profits from others’ misery and mistakes.

People are not their crimes. They are not committing the crime that got them in jail, over and over again each day that they are in prison. However, our penal system treats them this way and refuses to deal with them as persons. It was important to us to take this out of the equation when people encounter Prisoners’ Inventions. They are not able to dismiss the work or to fall back on only focusing on the crime that Angelo, or the other inmates whose inventions are presented, committed. We were accused of everything from being hypocrites, about the ethical standards we demand in our practice and that of others, to being immoral for not knowing about Angelo’s crime.

There is a flipside to this that has also affected our collaboration with Angelo. It is that for seemingly every positive application that an accepted object or privilege will have for one inmate, another prisoner will immediately find a harmful, violent, or destructive use of that same object or privilege. The drug and weapons trade is a good example of this. Where Angelo is incarcerated, books must be sent by an outside publisher or large well-known distributor because there have been too many problems with individuals hiding drugs in books and attempting to smuggle them in through the mail. Even bubble mailers can’t be used to send things for this same reason. Hardbound books are completely banned – in all likelihood because the spines make good hiding places for contraband. Restrictions like these prevent us from casually passing along a lot of books that a person like Angelo might really benefit from. There are a lot of restrictions that cut both ways like this.

One inmate (not Angelo), who for over two decades had been trying to better himself during a very long sentence, once made the comparison that ‘Being in prison is like being the only sober person on a road filled with drunk drivers. You waste so much energy just trying to avoid getting hit by the other drivers that it becomes extremely difficult to get where you are trying to go.’ Prisoners who are trying to do something constructive or self-advancing are in a really tough situation because many of the other inmates practice behavior (and inventiveness) that causes some of these restrictions to be put into place. For the prisoner that is trying to do something positive, the difficulties come from all angles.

Nonetheless, this project gives clear evidence that prisoners can make huge contributions. Not everyone is going to make these amazing inventions nor should we expect them to; that would be like expecting every panhandler to be a virtuoso musician because you’ve seen that a couple can carry a tune. But it does give us a lot of hope. Certainly some people, as you suggest, will always feel that doing anything with prisoners at all – that giving them any kind of voice - is giving them something they don’t deserve. One answer to that challenge perhaps lies in the absurdly high recidivism rate in this country. Based on the number of people that return to prison after they get paroled (often for crimes worse than the ones they committed the first time), it seems that we can afford to be a little more experimental in what some prisoners are able to do during their sentences. We can afford to rethink what they might contribute to society while they are still in prison. We can afford to keep thinking about how prisoners might be able to re-integrate into society upon release.

Not every person in prison is going to be worth the effort that we have made to collaborate with Angelo. But of course, this would be true if you made generalizations about collaborating with any random person in any random situation. People in prison are certainly no more likely to produce interesting art, writing, or ideas than any other random person. We certainly think that Angelo is a really exceptional artist – in many ways not even demonstrated in the Prisoners’ Inventions project. One of the nice things about Prisoners’ Inventions is that Angelo has highlighted the interesting achievements of others who, in some cases, might be far less enjoyable to work with than he has been.

AF: Angelo certainly is exceptional, and the material is certainly compelling. It is a hazard of my profession to lose sight of the particular person in the pursuit of “justice,” which is supposed to be blind and impersonal. This very hazard is what made Prisoners’ Inventions attractive to me in the first place. And this same hazard, this same perception that it is necessary to dehumanize in order to do justice, also seems to underlie the undeniable cruelty our society tolerates in prisons. Nevertheless, we seem to fall prey to the same tendency to depersonalize every time we talk about the structural injustices of the criminal justice system. The best thing may be simply to refuse to engage in generalized (and therefore impersonal) debates about justice and insist methodically, rigorously, on the humanity of each individual prisoner.

Assuming we want to talk about the broader issue of prisons, we quickly run into a difficult fact, which the prisoner you quote alludes to: nobody knows how run a good prison. When I say a “good” prison, I mean one that does both of the things you talked about—has conditions that are not appalling, and reduces recidivism. In the 1960s and 1970s, the dominant view was that prisons were for rehabilitating prisoners, and there were a lot more programs than there are now. But it turned out that for the most part these programs had very little effect on recidivism. The “failure” of these programs—along with a rise in crime and the broader rightward shift in politics—led to a backlash that resulted in the much more punitive system that we have now. Of course, making life worse for prisoners hasn’t reduced recidivism either, so I agree with you that we can afford to experiment. But it is so much harder to make improvements than it is to perceive the need for them.

JS: I’d like to talk more about how “Prisoners’ Inventions” functions when displayed as art within a museum or gallery. Rarely is there immediate cause for activism after pausing to read the wall label and to observe the object presented.

I agree that Angelo’s writings and drawings are compelling. But for me, what stands out is not so much Angelo’s technical ability to draw, but his ability to render and describe from a personal perspective what it is like to be a prisoner within a regulated system. I saw your recreations and the fabricated cell as part of the Fantastic exhibition at MASS MoCA. I wonder if visitors will be able to transcend the role of the art object and the neutral space of the gallery to think about and respond to the legal and political aspects of “Prisoners’ Inventions”. The exhibition title Fantastic implies the sensational or surreal, or as described in the exhibition literature:

In the fantastic, things could go either way. Poised between the possible and impossible, the fantastic is a destabilizing pause in the plausible, a moment for our utopian dreams and dystopian fears to acquire form. …This imagery, populated by alien lights, levitating hippies, and utopian schemes, teeter in the fantastic moment, beguiling us to linger there with them on the precipitous cusp of possibility. Philosopher Walter Benjamin believed that meaningful social transformation required these disorienting moments just beyond the real: In his view, the fantastic is a powerful tool for preconceiving – and reordering – our world.

Temporary Services, how did you approach showing “Prisoners’ Inventions” at MASS MoCA and what kinds of decisions or considerations did you have to make regarding its method and context of display?

I feel if “Prisoners’ Inventions” is meant to be a means of education and insight into the penal system or issues surrounding freedom of expression, additional sources of information and outlets for response could be provided in conjunction with the show. Some suggestions would be to provide a study room where information could be easily accessed through pamphlets and books, provide Internet access to web addresses, and/or to give related organization contact information.

But perhaps this point is confusing because the book “Prisoners’ Inventions” does not pretend to have a particular agenda. It is the writings and drawings of Angelo. How important is it for there to be a means of response from the viewer?

TS: We don’t worry about if the inventions Angelo describes, or our recreations of these inventions, are art objects. They are objects of enormous creativity and imagination – for us that is enough. We often say that the distinction between art and other areas of human creativity is meaningless to us and this is one of those situations. One of the great pleasures of working with Nato Thompson (curator of Fantastic) is that he did not feel the need to justify the inventions as art by calling them “readymades” or trying to place them in some kind of art historical trajectory. Certainly, the inventions were not thought of as art by the inmates that made them to cook or light cigarettes.

As you note, the degree to which Angelo describes the prison experience in this work is really important. It is telling, and exciting, that instead of people getting hung up on asking “How is this art?”, most people move right into the content of the project and ask us for more explanation about why things are restricted, or they try to get a greater sense of other prison issues and what Angelo’s situation is like. In this way, viewers seem to move beyond the museum context quite easily.

For MASS MoCA we decided to keep things focused entirely on the drawings, writings, inventions facsimiles and the recreated cell. There are so many things that can be discussed in Prisoners’ Inventions and it is through dialogues like this that we have been able to illuminate other concerns in the project that are less easily discussed in an exhibition format. We can discuss prison and legal issues in this dialogue because it is an opportune moment; this is Aron’s field.

We had space limitations at MASS MoCA and could not show anything more than what was included. We had to omit some of the inventions that we recreated. We had great budget constraints so our entire budget was used to get us there and to build the cell. We had to keep in mind that this project was also part of a larger show and it would be unrealistic to add too many additional elements to what was already a complicated presentation. The presentation already requires a great deal of reading. It would probably take at least 30-45 minutes to read all of Angelo’s inventions writings that are included in the vitrines. It has been a great complement that we saw many visitors putting in the time to do this.

But, to respond to your suggestions - we have generated a lot of supplemental research while working on this project – information about inmate inventions that we found in other sources – and something like a study room could be a logical part of a future presentation. We have been tossing around some ideas about how the project could be expanded in different exhibitions. We know Angelo has made some more inventions drawings that we haven’t seen yet. We don’t see the show at MASS MoCA as definitive and unchangeable.

The process of proposing, debating, and ultimately realizing Prisoners’ Inventions at MASS MoCA was incredibly intensive and much too long to fully describe here. Students from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago that helped us with the project conducted an exhaustive interview with Nato Thompson that you can read here. He does a terrific job of describing a lot of the difficulties we ran into (including problems with an original proposal we submitted before Prisoners’ Inventions).

We don’t view this project as a direct call to action in terms of prison reform – it doesn’t prescribe a particular type of response in order to effect change. That wasn’t our reason for doing this work. There is an activist component in making sure that voices like Angelo’s get heard. He, in turn articulates the ideas (inventions) of a lot of past cellmates and so there is a chain of information that he has worked with us to get circulated. There has been a huge amount of mainstream U.S. and international press on this project, which has spread information about the creativity and imagination of people in prison far and wide. We have been spending a lot of time following up on press inquiries. It is important not for our own promotion but to promote these ideas about prisoners’ responses to their repressive conditions. Angelo’s drawing of a motorized tattoo gun was featured in the “Ideas” section of the Boston Globe. His writings have been read on National Public Radio’s "This American Life"and they have been reprinted in Harpers. Shows at MASS MoCA stay up for a year and reach a lot of people, but the press has brought aspects of this work to millions of additional people.

We have been participating in dialogues like this in order to shed light on the kind of work that it is possible to do with people that are incarcerated. We can talk about the problems we ran into and how we resolved them. We have been working to make people aware that prisoners are a population that can still participate in the world. The press has probably helped us to share that information more strongly than the exhibition at MASS MoCA, however the exhibition component provides people with a more tactile experience. The book that White Walls published is more intimate so that is another kind of experience. There are multiple levels. All are important to us.

----

Prisoner's Interventions by Angelo & Temporary Services is on display in Building [4] at MASS MoCA through the Spring.

All images are courtesy of Temporary Services and MASS MoCA.

Jennifer Schmidt lives and works in Boston, MA. She received her Master of Fine Arts degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1999 and Bachelor of Arts degrees in Studio Art and Art History from the University of Delaware in 1997. Recent exhibitions include: “OCD” at Mills Gallery / Boston Center for the Arts, “Repeat” at Transport Gallery in Los Angeles, “Suddenly” at the Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts in Wilmington, “Ocularis” at Video Screening in Brooklyn, “Experimental Sound, Video and Film Programmation” at Institute Jean Vigo in Perpignan France, “Mybrary” at BUILD in San Francisco, “Repo(session)s” at Gallery 312 in Chicago, “Sensitized Shopping” at Silicon Gallery in Brooklyn, “FGA, The Stray Show” at Thomas Blackman Associates in Chicago, “LINGO” at ONI Gallery in Boston, “What I Did This Summer” at Allston Skirt Gallery in Boston, “Living, Room” at ARC Gallery in Chicago, “Consumer Product Installation” at ARTSCAPE in Baltimore and “Inherently Pink” at SPACES in Cleveland. Recent publications include: Collezioni:Edge Magazine, and Eleven Bulls. Her work has recently been reviewed in NY Arts Magazine, New Art Examiner, Art New England, the Boston Phoenix, and Philadelphia Arts Matter. Jennifer currently teaches within the Print and Paper Area at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Chess Set, 2003 by Angelo & Temporary Services @ Mass MoCA.

- Muff Bag (Homemade Sex Doll), 2003 by Angelo & Temporary Services @ Mass MoCA.

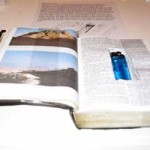

- Sanctuary (lighter hidden in bible), 2003 by Angelo & Temporary Services @ Mass MoCA.

Temporary Services

MASS MoCA

Jennifer Schmidt