TRENDS IN PRE-FAB METAPHORS

While in the earlier 20th century Brancusi exploited innate, archetypal forms that one could call the ultimate pre-fab (the egg, the sphere), and Minimalism's arrival in the 1960's carried pieces like Tony Smith's Die into the cannon of art history (I still remember the day I found out that there were more than one Die and that in fact it made absolutely no difference how many there were, because they were not sacred objects in their own right but rather represented an amazing freedom from the heavy weight of the essential object), a group of contemporary artists are setting a pace for reassessing the useful in modernist design, undergoing a similar essentializing phenomenon with one caveat: in terms of portraiture or the portrayal of a figure, the individual is sacrificed for the group, in fact, transformed into a member of a group.

Taking the perspective that art is a by-product of life, a kind of result that is produced as an actualization of a way of being, Greg Mamczak's work shows us how this preoccupation manifests itself in art as an attempt to tighten representation and to hone metaphor through the most economical means possible – the pre-fab. The work of Mamczak shares a curious tendency with other artists who point to a larger trend of economization, reduction, repetition, and pre-fabrication in structure, method, and articulation. Dimensionality, the objects in his paintings are flat, like a ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock print or the Art Nouveau posters which were inspired by them, existing somewhere between a graphic rendering and an icon.

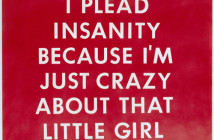

Emotionally, Mamczak's paintings are brooding, ominous, esoteric, expansive. Using a silhouetted style, his approach formally reduces the subjects of the paintings so their iconography works more as signage rather than artifice, and ties them to a current cross-disciplinary preoccupation. Working with a basic arsenal of visual tools, Mamczak's paintings employ dramatic economy of form. They are assemblages, blank slates with interchangeable parts that are easily manipulated, arranged and re-arranged, their subjects paired down to an ultimate utility. What becomes evident is that economy is a method for how he works – his means of arriving at the quickest and most efficient way to illustrate an idea.

Can a pattern or pre-fabricated form be artistically informed by the end user? To flip this method a bit differently, we can consider the actual shape – the anonymous cut out on its own terms rather than as a repeated element. Artists have taken this economic form of depicting an individual as an icon or punch out shape – finding that not only is it a more efficient means of expressing a story, but that there is not a definite need to express the identity of the subject; that the forms are are again representational and can "stand in" for any member of a kind of group. Figures are interchangeable, representational objects, identity is moot.

To parallel, another artist employing biography to this form is Do-Ho Suh. Korean by origin, many of his images, as Mamczack follows up with, deal with a redundant repetitive figure that forms together into a critical mass, actualizing a metaphor. In Doormat: Welcome (Amber), thousands of amber colored polyurethane one and a quarter tall rubber figures, essentially human, compose a large scale welcome mat, working to challenge our notion of scale and our ideas about support. Instead of folding into the typical group vs. individual theme however, Suh points to the realization that anonymity does not truly exist. Making the deliberate point to call attention to these are individuals over a wash of anonymous figures - he is still using a six-figure method to express entire populations in his pieces.

The larger metaphor of prefabrication, is economizing for a large number of users. What does this modernist dream of utopian manufacture mean today? What is that legacy as an emotion, as a global consciousness? Positing a dilemma between pithy, acute identity and representative anonymity/obscurity, artists from roughly the past ten years have been building a way of seeing that recognizes a mass over an essential distinct being. These artists are able to reduce figures to placeholders that make quantifying, rather than qualifying judgments, and question what political, emotional, or social commentary is made by the use of representational repetitive figures. Considering what it means to move between a collective and a specific viewpoint, the identity of a member of a group can appear unimportant as long as the group has an overall brand, bringing up the bigger question: is being part of a whole is more existentially significant than being just one?

This visual/methodological based relationship imparts an alternative way of operating; he is not hand-crafting immaculate subjects; rather, it is reproducing, cloning, multiplying a dominant form because of its successful characteristics - this is genetics, this is finding best practice.

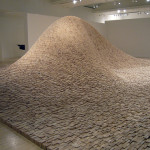

Maya Lin, most renowned for her commission for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, is also responsible for installations that reference landscape made entirely out of an essential, repeated volume. One piece, entitled 2x4 Landscape that was installed at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, Washington in 2006, is indeed made expressly from two-by-four wooden blocks. It is a gently curving, yet hugely impressive landscape (stretching 2400 square feet and reaching approximately 10 feet tall at its height) with sensitively curved troughs and peaks, appearing almost pixilated like a digital scale model manifesting the data from the geological measurement of a hillside. In fact, she completes the actual installation from an intricately detailed model. What strikes a chord with this work is that the entire piece is composed of interchangeable shapes that can be formed into a geometrically dynamic landscape.

Here lie notions of social responsibility and sustainability, in the same vein of efficient energy, localvoreism, fuel economy, emphasis on carbon footprints and organics. This recent ethos, which has boomed its way into the status quo, from grocery stores in the suburbs of Northern New Jersey to West African slum villages, has become a commercially accepted norm. What is relevant is the relationship artists have cultivated between this economy of form and its association with manufactured culture and and pre-fab logic? Mirroring contemporaneous design sources like Dwell and IKEA, and the recent move toward pre-fabrication in green and energy efficient housing. The interchangeable qualities presents subjects as pieces of a whole that are efficiently combined. In method, repeating shape is a kind of exercise of discipline; a process oriented procedure that is more about arriving at an aesthetic.

- Greg Mamczak, Untitled, (Factory), 2009

- Doh Ho Suh, Doormat: Welcome (Amber), 2004

- Maya Lin, 2 X 4 Landscape, 2006

All images are courtesy of the artists and Google Image Search.