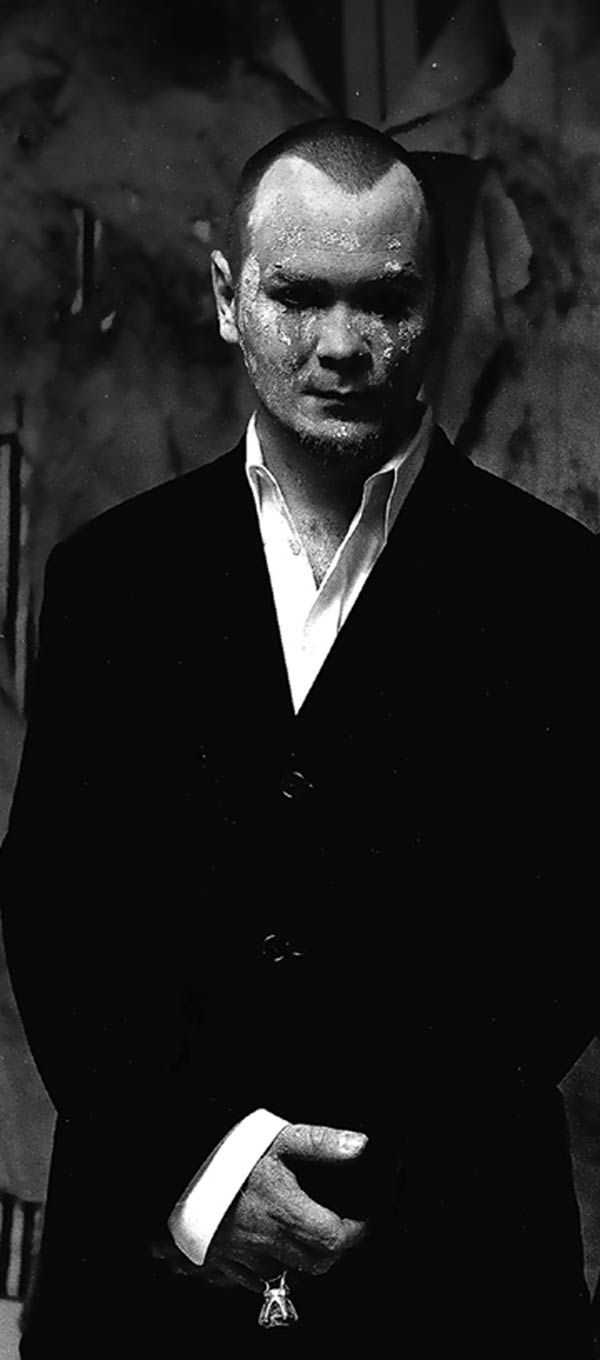

A CONVERSATION WITH LEON JOHNSON

Leon Johnson is the Berwick Research Institute's new Director in Residence (DiR). Having just taken over late in 2008, he will lead the Berwick for the next two years.

The organization has been without a Director since Meg Rotzel's departure in 2006 and their new DiR program is an innovative approach for a small non-profit to bring experienced leadership to their team. On their website, the Berwick says it is bringing "unconventional creative practices into the arena of experimental arts administration."

Johnson will starts his residency with a series of discussions, called Convivial Symposia, that the Berwick will employ as seed material for a new publication.

Big RED Executive Editor Christian Holland spoke to Johnson shortly after the first symposium in late January.

Christian Holland: What do you see the Berwick as now and what will be your approach to the Berwick in the two years of your residency?

Leon Johnson: There were three months of orientation and one of my priorities was making sure - In systems like this which move with very little resources, very inventively, people can get taxed and exhausted, people are multi-tasking, so I wanted a sense of how everybody was doing and what they might need, in terms of the curators at A.I.R., my two colleagues in SPI, Daniel [DeLuca] and [Ryan Sciaino], how we were going to think about a new funding model because the LEF funding cycle concludes this year. So in a way, I came in as the first director in residence, but I came in when the entire Institute was renegotiating individually and collectively about where to go, so it was pretty thrilling. I have an interest in interfacing with these domains, commerce, simply where we can build alliances, between knowledgeable empathetic co-producers. So, for example, we would love commercial interests to co-sponsor a lecture series. I think we should be prepared to understand their motives and their operational priorities, how they are thinking about new paradigms for higher systems, and the Berwick should be very clear in terms of needing to be agile and creative. With any number of collaborating partners, the emphasis, I would hope, is always on making it creatively viable and - to as much as a degree as possible - having some pleasure in devising new ways to partner.

CH: Who are some of your ideal partners?

LJ: Dream partners?

CH: Dream partners, but also the most ideal partners here in Boston.

LJ: People I’m talking to range in (laughs) – my last meeting. (I spoke with Johnson immediately after he had a meeting with Catherine D'Ignazio: kanarinka of Platform 2 and iKatun). People who are enthusiastic, eager to immerse in process of building, so I’m really less interested in someone saying, ‘Yeah, we can sponsor a flyer,” than for someone saying, ‘What does a creative partnership mean?’ or ‘What are models we might look at?’ That kind of stuff I’m hungry for. Those kinds of conversations where we co-author initiatives together and I suspect take ownership in a richer way - - some empathy for the various paths we’re all on - this woman from Tel Aviv, Bracha Ettinger, calls besidedness, to walk in intimacy with someone who has a very different platform or set of priorities and co-author initiatives together while maintaining separate identities - - so I’m eager for the Berwick to rethink what audiences mean.

The symposium series - why its emphasized as a convivial symposia – one of my personal interests in my own work and in my pedagogy, is the power of food in building some of the conversations. There’s a fantastic operation I’ve been keeping an eye on in San Francisco called Open Restaurant. They’re nomadic and they provide groups of people with all the tools necessary to set up kitchens and more traditional sites – backyards, neighborhoods. They’re connected to networks of gleaners and foragers, and they’ve got this beautiful list of people, for example who home-produce - somebody’s got six jars of wild blackberry jam, somebody else is growing a small patch of leaks, somebody else is wild harvesting honey in the Oakland hills - and they network these groups of people into a system called Open Restaurant. Food is important to me. In my teaching I had a group of students open a restaurant for a week – design, produce, build, meet with lawyers – and we served 200 lunches per day and then ran a parallel soup kitchen. I’m very interested in talking to farmers markets and restaurants – places of convivial engagement. From a plate a food you can navigate anywhere into issues of ecology, into commerce, into biology, it’s a great trigger.

CH: You were just in a meeting with Kanarinka of iKatun and you also mentioned earlier the community aspect of your plans for the Berwick. In what ways will community be involved in the Berwick’s programming under your leadership?

LJ: Catherine [D'Ignazio]’s a great example. She graduated from MECA; I taught there. We met at the first Convivial Symposia and within minutes we were talking about Platform 2 and her set of operations my interface where can support each other. They also have a lecture series unfolding in the year and it would be the simplest of systems to join whenever we can in useful where we can have audiences meet each other. We’re very eager to have the people we’re bringing in interface with the academy - with classes and students. This notion to make it as inclusive and porous as possible. I’m hoping that the conversations multiply and cross pollinate into initiatives. I’d love the Berwick to be a comfortable think tank for people to bring developing initiatives that we can offer think tank services and conversations. The primary initiative that pitched the Berwick during the interview process was a convivial symposia series where I bring in eight to 12 guests over the next 18 months. They spend minimum of one day in a think tank – Berwick exclusive. Everybody coming has a sympathetic practice or something we can learn from. Our first guest was J. Morgan Puett and she primarily spoke about a developing 95 acre operation called Mildred’s Lane. In the second day they present to the public in the context of an open kitchen – sometimes it’s going to be buffet sometimes it’s going to be a restaurant setting, sometimes a lounge. We’re going to be responding to wherever we’re going. It’s a nomadic series.

CH: What kind of programming are you going to bring to the community that the Berwick is situated in?

LJ: It’s going to be at least three pronged. SPI is developing initiatives for new programming – incubation of new works – AIR, in addition to hosting artists to support research will hold public events. My hope is that across the programming platform we keep agile and responsive. I think the Berwick has a history. I think the Berwick has enormous work to do paired with enormous potential in its home site – I don’t think it’s done nearly enough there. When we first started talking about the outcome of the convivial symposia, one of the outcomes was a book – a psycho-geographical field guide to culture-making in the 21st century. When I originally pitched it, my interest was a deep analysis and study of Roxbury. What awaits us there in terms of the archive of how it’s being used and inhabited; what is its current demographic, what does it offer in terms of potential, where can we partner. It seems to me a geography on the cusp of 25 potential outcomes. It’s tender, it strikes me, in terms of where its poised. I think it would be a remarkable accomplishment for the Berwick to land and migrate into the community into the community. I don’t think it’s really done that.

One of the ways that I think about new audiences, for example: the other night at our [first]convivial symposia, a good portion of the audience was students. They arrive at an event expecting the academic tradition: you sit you take notes. The idea that much of what we’re going to be talking about suggest that you move from an audience member towards becoming an author of content and of initiatives – almost every guest I’m bringing in will come at the idea of producing, promoting, disseminating new work around the idea of designers as authors – the hope being that something J. Morgan Puett spoke about at the first symposia: inventing systems - being rigorous in the cultivation of sustaining conversations – can actually, fuel initiatives into production and application. One of the ideas is that I would want students to come to engagements less exclusively at receivers and more as ignition systems in training.

CH: You talked about the LEF’s funding cycle coming to a close, but the economy is also in recession. Do you see that as a barrier?

LJ: I’m going to sound like a wanker now and say I actually see it as an opportunity. I really do. (laughs) I made a joke at the [first convivial symposia]. The DJ I hired was my 12-year-old son and he was DJing from his little Korg DS gameboy. It was just incredible. At the end of the event I said, ‘One of the toughest, most draining parts of the DiR position at the Berwick is to agonize about all the money they throw at me so I’d like to introduce this legendary east coast DJ. We flew him in…’ It was a sort-of joke, but it also articulated an initiative. I’m doing this project not in Portland. It’s a political burlesque dinner theatre. I got a “Good Idea” grant for $1,500 and 20 people are participating and making this happen. Everything from architects to chefs and farmers – everybody with an average of about a $125 budget and everybody fully engaged. It turns into a remarkable chorus of initiative and enthusiasms and you sustain one another. I think if it’s passionately and truthfully articulated around opportunities for collective authorship for the birthing of new initiatives people will come – creative strong people and we will be able to building these new paradigms.

My preference is that everyone who participates is to some degree rewarded – ideally, paid – for services and skills. That’s my priority. We need, however, to stay active, we need to feel we’re operating with a minimum amount of compromise, and still feel some sort of opportunistic creative fervor. God knows the narratives we may deliver, the spectacles we might author, all the stories we might tell: they’re critical. The time needs it; people need it. We need to defer as little as we possibly can in the absence of support. We have to be active. That I suspect is going to be part of what I leave in the 24 months in terms of my narrative. What have I learned? Where was compromise unavoidable? In what instances did incredibly generous and empathetic participation, in fact, author remarkable content that we can stand behind with some conviction and pride. I want a good chunk of the narrative reflect how we face these kinds of difficulties.

CH: From what you’ve seen so far what do you like about the Berwick and about the community that’s now your sandbox?

LJ: Throughout the interview process and throughout the three months of orientation, I’ve not heard ‘No.’ After 12 years in the academy, man, that’s pretty sexy.

The Berwick Research Institute

Images courtesy of Leon Johnson.