Taiwan is a small democratic island nation just off the coast of China. Considered a rogue province by China, Taiwan's recent history has included 40 years of martial law under Chang Kai Shek's Nationalist regime, but also rapid industrialization and a booming economy in the last three decades. Despite this increasing economic prominence, due to ongoing hostilities with China, Taiwan is only formally recognized by a handful of countries in the world.

Last year, while on a Fulbright Scholar Fellowship, I interviewed a number of prominent Taiwanese photographers for an Aperture Magazine article (to be published in the November 2010 issue). Included here are a variety of important interview excerpts that were not included in the final edit.

Chen Chieh-Jen is a prominent Taiwanese photographer and video artist. Shows of his include those at the Tate Liverpool, Venice Biennial, Shanghai Biennial, and the Asia Society in New York. His current show, Empire's Border's II is on view at REDCAT in Los Angeles until September 5th.

BRS: An aspect of Lingchi that struck me is how, from a Western point of view, the subject seems to be a Christ-like figure, this young man with a weary saintly look, receiving torture as a punishment for the greater society.

CC-J: It is difficult for westerners not to associate the image of the lingchi victim with images of the suffering Christ. This is especially so because the victim had been anesthetized with opium, causing him to look up at the sky with a smiling expression. In his book, The Tears of Eros, George Bataille notes the victim's expression of ecstasy, and then deepens the connection between this image and Christ imagery. I don't necessarily disagree with Bataille's philosophical and aesthetic interpretations, as I said before, I think his explanation actually broke free of biased western-centered perspectives. My concern isn't how Bataille has interpreted this image, but rather that most westerners see this photograph from only his viewpoint, and this has restricted the explanatory space for this image.

BRS: But if there is such a misrepresentation of Asians by westerners, wouldn't this happen with almost any artwork created by Asians? Do you feel your work is bounded by cultural misrepresentation by westerners?

CC-J: Everyone views other cultures through their own cultural bias, not only westerners. The problem is that dominant cultures always mistakenly believe they have the ability to interpret others, and always situate other cultures within their own cultural context in order to understand them. This is the part that interests me as an artist living in a non-western place. I am not worried about being misunderstood, since to a certain degree misreadings between cultures have always and will always exist. In addition to maintaining dialog between cultures, we must also point out prejudice and do all we can to eliminate it.

From another point of view, misreading can also be a starting point for pro-active dialog. Just like this discussion about the lingchi photograph, which has made it possible for us to move beyond the single interpretation of Christ imagery toward multiple discourses.

BRS: What then do you think are important facets for an American audience to know about the Taiwanese context in terms of relating to your work? How do you deal with the lack of context by those viewers?

CC-J: I don't think there has ever been any simple way to create perfect understanding between different cultures, rather it is a long process. Artists outside of mainstream western cultures shouldn't have to pander to stereotypical cultural impressions or fall into the trap of Orientalism in order to be easily understood by those dominant cultures. Instead they should continue to present their own viewpoints without fear of being misunderstood. Again using my film Lingchi as an example, besides Christ imagery, I think this work is also discussed from the perspective of exploiting spectacle and exoticism, or for aestheticizing violence, but these issues still open up more space for discussion.

In some ways, communication with the audience doesn't come from ease of understanding, but instead from the confusion produced by something difficult to understand. Sometimes confusion is the beginning of deeper communication.

BRS: Here's an interesting situation of a Chinese subject being photographed by a Frenchman, made into a video by a Taiwanese, then presented in Italy at the Venice Bienniale or to Americans in an American exhibition.

CC-J: I am interested in creating conditions where people will become interested in the subject matter and really pursue what is behind the image. When people feel interested in this issue, then they will start having questions. Like Europeans will recognize: “Oh, that is a George Bataille photograph!” and relate immediately to the George Bataille point of view on the subject. So I reimagine it as a video, then the viewer will become to ask why? Then they may discover that the original George Bataille perspective was a result of a misrepresentation, and they will begin to develop a new point of view on the subject.

There is the example of Matthew Barney, who can explain what his work means to us, an Asian audience? We can't understand! But the Western viewers who have the ability to understand English, who have the rights to speech, it's easier for them to interpret or write about his work. For us, in the marginal area, who has the right to interpret his work?

BRS: But Matthew Barney's most recent video (Drawing Restraint 9) takes place in Japan. What's interesting is that he's trying to immerse himself into another culture, but there's a lot of his own misunderstanding projected onto that culture.

CC-J: He's got a real interest in the culture, but the culture balance is not equal there, so maybe in this situation if Matthew Barney misunderstands an aspect of Japanese culture, it's not a big concern for him.

BRS: I'm interested in your work in terms of power. It seems that the subjects in your video are under a certain authority over the individual that is manifested physically. How do you use video to confront this expression of physical power?

CC-J: Use of power in the contemporary world is often difficult to see. I am interested in how to make these invisible things seen, and this implies that I have to think politically about raising issues. Regarding my video art, it isn't just about how to present the internal workings of an image, but also how the issues are played out in the entire filming process, and therefore, I also think of each film shoot as an action. For example, for my videos Factory and Bade I used spaces that had been closed down by the courts, and therefore had to sneak in illegally in order to shoot these films. To some extent, occupying the site and shooting the films transformed an originally legal and capitalist space into a critical field. Furthermore, by letting workers, who had lost their jobs due to an iniquitous factory closing, to return to their former site of employment, I allowed the brutal reality of globalization to be seen.

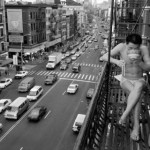

Chien-Chi Chang is a Magnum Photographer who has published a number of books, including China Town, I do I do I do, and The Chain. His most recent work follows North Korean defectors fleeing into China, then into Laos and Thailand, on their quest to be reunited with relatives in South Korea.

BRS: Could you describe what your process is – how you conceive of a project, then take the necessary steps to see it through over a number of years.

C-CC: (With the example of ) China Town, I can stay on this project for so long part of it is coming from my own experience. I'm partially an immigrant, I'm just going back and forth (between countries). We all do research, to read as much as I could, but also to be mindful to not let what I've read dictate or influence what I see. To go there with an open eye. I suppose. But it has been true over and over that to find the right people to take me in is the most important, being a stranger in a closed community. Even to this day, after all these years, I'm friendly with a look of the Fukienese who don't have legal status, they still do not want to be photographed.

BRS: People think of a photograph as being such a direct representation, but there seems to be a superstructure around it, behind it, that we don't see. How important is that context for people to engage your work with?

C-CC: I don't think its direct, when I was working at the Seattle Times and Baltimore Sun, I was trained that the photograph should have this impact , or else the reader will just go to the next page. For magazine or personal projects, that's not the case. I would try to photograph in such a way that there are means, or visual ways to enter to view the photograph. Yet it could be open for interpretation, it doesn't have to have this same direct impact.

BRS: I've always wondered about how news photographs have such a short lifecycle: they may be on the front page one day, but by the next day there's a new photograph and the previous day's one is forgotten. With personally driven projects like yours, it's about a much greater situation, not a specific story, there's a very different context.

C-CC: News photographs tend to have a very short lifespan, unless it's a major historical event. Back then, in my newspaper days, I was already doing the personal projects. It was one of the reasons why I left the newspaper. You do two or three quick assignments in one day, you drop off the photos, they publish it, and the next day you go out. It was clear when I was doing my first newspaper job that I that I wanted to spend more time on a project, to go a little bit deeper, and that takes time.

BRS: Do you find a different response to your work whether you have an American audience or a Taiwanese audience?

C-CC: Yes, definitely. With the work that needs more cultural understanding. The Chain was shown in 2001 in Venice, I still remember two questions. 1) Are these people actors? OK, I can understand that question in a Biennale situation. 2) Were these photos taken 50 years ago? People in Taiwan, would not ask that. Well, maybe the younger generation would. The people over 30, over 35, they know. They're aware of the situation.

BRS: Do you find that a Western audience may expect to see certain aspects represented of Asian culture?

C-CC: I can't really think about what the viewer's mind perceives or how they read the images. Hopefully the photos are can communicate with the viewer, the readers, I think there can be danger if there's only one way of interpretation. “this is the only way of looking at this picture”. To me, the visual communication, there's always an ambiguity in there, to put it in words, I know it's there, and people with different cultural backgrounds will read it different. There are certain things that I'll avoid, like writing or words. For people who can't read that, it completely becomes just a graphic thing. For the most part we all communicate on a similar emotional level.

BRS: is there is shift in how you work, especially given the vast volumes of images available in this internet age?

C-CC: There's a democratization of the photographic image, but in terms making good photographs, that hasn't changed. There's millions of photographs being uploaded, but don't get me wrong, there are some good photographs there.

I'm more interested in projects, and not just one project, but a link between the projects. Ten, twenty years from now I want to see a bigger picture there, among the work that represents me. I do see with my later work: The Chain, Double Happiness, with the new work I'm doing on North Korean defectors...

BRS: Could you talk a little bit about that project?

C-CC: I travel with them from the North Korean border to China or Russia, all the way to the south, cross a mountain into Laos, then cross the Mekong to Bangkok where they surrender themselves. After two months in a detention center, they're sent to South Korea.

This is Asia's so called Underground Railroad.

Yao Jui-Chung focuses on a photographic practice, but also extends into the realm of video and sculptural installation. His series of work includes, Roaming Around the Ruins, which documents the industrial vestiges of Taiwan's rapid modernization.

BRS: How does your work confront the issues of Taiwan's political past or engage with the identity of being Taiwanese?

YJ-C: My photography works are, like Don Quijote de la Mancha facing the windmill, attempting to grasp the enigma from the tangled history. If Taiwan is to face or establish its entity, it has to first recognize the enormous influences by the feudal consciousness from the Chinese culture and the imperialism from the West. A lot of my works in the past 15 years are dealing with the preceding problem; they illustrate the entity and consciousness of Taiwan through the strokes of irony.

Accordingly, I will start to deal with the following issues. Although a lot of people consider my photography works to be politically influenced, I personally do not have a bias in favor of any political party, and I am never involved with any political activity. I just feel like to participate in this abiding historical moment and rewrite it somehow with my particular ways of rendering through actions of laughing and abusing. In the end, I could, therefore, ponder on this everlasting question of who I am, where I come from, and where I should go.

BRS: Do you see a barrier for a foreign audience who cannot directly relate to the cultural associations present in your work?

YJ-C: This is indeed a problem, but I do not desire to follow internationalized approaches in order to be better acknowledged. Because I know as soon as I begin to do it this way, I would be contaminated by the ideas, and violate the original intention that puts me engaged in photography. I believe through photographing, the truth could be seen through and realized instead of cloaking in disguise.

This, somehow, reveals a more critical issue. People of the developed and so called superior countries often conceive cultures from the rest of the world with their wishful ideas, and result in misunderstandings and wrong impressions time after time.

BRS: Do you see other unique challenges being a Taiwanese artist in a global setting?

YJ-C: During the cold war era, Taiwan contributes evidently to the world; under the inevitable globalization trend nowadays, it still manages to make significant contribution. Somehow, the relentless political stalemate between China and Taiwan stands in the way. The world blindly gives much of its attentions to the Chinese artists, only to overlooks the importance of the Taiwanese artists.

Consequently, the greatest challenge to the Taiwanese artists is not the ability to create a striking piece of work but to make the world conceive and understand their works for lack of decent means. Unavoidably, the artistic society becomes interfered by having political perceptions, and unable to come around.

- Chien-Chi Chang, from China Town series

- Chen Chieh-Jen, still from video Lingchi

- Yao Jui-Chung, Presidential Palace

All images are courtesy of the artist.