By James Nadeau

I had the opportunity to sit down with Nicole Cherubini and Taylor Davis as they installed their show Davis/Cherubini, In Contentionat the List Visual Arts Center at MIT. The work is truly a collaboration between the two, which makes the title of the show somewhat unsuitable. I didn’t get the sense that there was any disharmony between the two artists, and was amazed at the ease with which they worked together. The freedom and security that their working partnership gave them was really great to see at play - JN.

*

James Nadeau: One of the first things I wanted to talk to you both about is exploring the notion of collaboration. Because I think that, coming from an art school background where one is taught to work by oneself, makes the very concept unusual. I am curious about the process. Was it an organic process where you both liked each other’s work? Did it stem from a conversation? I am curious about the origins of the relationship.

Taylor Davis: Do you mind if we sit? If I am standing I won’t be able to resist the urge to move things around.

Nicole Cherubini: Well, do you know the story of how it happened? I knew Taylor’s work as we both showed at Samson Projects. And I had known her work but I had never met her and vice versa. And so we were out to dinner one night and we just sort of realized that we were in very similar places but with very different outcomes. And so it just kind of came up that we should try collaborating. As an artist I’ve had this conversation with multiple people, it just sort of came up, but it’s the only one that has come to fruition. I think that’s, I don’t know, I think that’s just because it is coming from this place of honest want. Kind of this like, you know you brought up earlier, the idea of ego. I think that is one thing that has been pretty amazing in our collaborating. We haven’t really, like we never try to cross each other out. Which I think is what happens a lot of times with collaborations.

TD: It was interesting when we first started making things. I remember somebody in New York was saying to you, you were in your studio, and said, “Why don’t you just crush that thing you know. Crush that part that you have. And then you can basically turn it from its object-ness into a material and then incorporate that into your form.” And we felt really early on that, well, that would be so easy. You know, build a little Robert Morris box around it. You know, a sign of it’s own crushing.

NC: Then it would like a freshman Foundation project! (Laughs)

TD: And then think “yeah! That’s easy!” (Laughs) But, what’s interesting is we knew that that would be easy. But there was also this sense of wanting to do the harder thing, which would be to really understand, in a different way, than the person who made it originally understood it and then separated from it for a good reason. You would say, “Well, what is this?” So the collaboration in a lot of ways is just this question that we both continue to ask when we are working on these things. How can I make this something? How can I take Nicole’s work and make it just my own?

NC: And also I think that asking that question, I mean, we are a different collaborative in that we work separately. But by asking that question it’s never…the objects are never treated like found objects. Which I think would be the downfall of it. It would be…

JN: So it’s more about process? It is a step towards something else?

NC: Yeah, it’s like, you know we’re looking around and realizing how we’ve just made some really weird sculptures. We can’t…(laughs)

TD: Are you calling it sculpture?

NC: (laughs) and both of us, with the way we work, we also can’t just take the objects and make something interesting. That is also treating it like a found object. You know? Or how do you make this sculpture? That’s not the question? It is how do you deal with this object? What can you learn from it?

TD: That was a thing that we learned early on too. I remember when I was trying to make Downstairs before it was Downstairs and moving this piece that Nicole had given me around and setting it up on a plane of birch ply setting it this way and thinking “That looks good. That looks good and so what?” It had nothing to do with the thing itself. I mean in order to make my own sculpture. It is like really trying to get my mind around um…how to recognize it, how to recognize the part. And the thing that is interesting about our working together is that it’s not like I’m trying to recognize it by reading Nicole’s mind. It’s that I’m trying to recognize something about it that Nicole might not have. And the thing about it for me was, when we were first starting to work together, I wanted her to understand something about my work that I didn’t understand. Like, I don’t get it. I want some relief from this. How do you see this? How do you see this form? So that is really key. It is this sense of this sort of pass off.

JN: Well it is this combination that is putting together entirely new forms that are so grounded and so based in art historical moments, like the amphora and Donald Judd. It is these things that are such a part of art historical training but through this combination you are resisting it or moving beyond it in a way that I find really fascinating.

TD: Well, we both try to move beyond that in our own work, me, with the amphora and Nicole with Judd. You know, pre-Donald Judd there were a lot of boxes. There were a lot, a lot of boxes. So we already have this sort of practice of not accepting an object’s immediate associative source as the important starting point. We bring that with us and then we have these things that are actually made by the other person. So we know their source but then there are all these other sources that are there in the making. A lot of what has been happening is the combination of how fun it is and how hard it can be.

NC: There are times when it is absolutely invigorating. You’re like, “wow the world is open, I can do anything. This can be anything. I have no rules!” Then the next day you come back to it and are like “this sucks! Why am I doing this?” (laughs)

TD: I know! “I’m yoked to this thing” (laughs)

NC: One of the first pieces, the taller piece, and I kinda figured it out in some way and then I got this other piece and oh my god. I was in this bastardly mood for like two weeks. And finally my husband came over and he’s like “just knock one of the things off.” So I started knocking off the rails and in that moment I was like “whew!” And then I put it back together and it was joy and happiness (laughs). So it’s a very up and down process.

JN: It is interesting that the methodology you have created for yourselves are so inherent in other art. If you look at filmmaking there is no one person involved. It is really about feeding off of other people to guide you or to see your blind spots. So it is this really interesting movement that is not how you are trained to do things. That’s not how you make work. You are supposed to come to it with a sense of self. This is my object and there you go. There is no letting go.

TD: The one thing that is funny about that is we haven’t seen these things together ever, all of these things. And one thing that I am sort of feeling in the room is you know, I’m just seeing things that I brought Nicole, and Nicole brought, that we can’t get rid of. And it doesn’t have to do with material but with sensibility. Which is really funny. The reason why I am bringing that up is, this idea of having to hold on to the ego and insisting that you make something that looks like yours, and is myself. If fact I can’t get rid of it even if I want to. No matter how different these things are than what we normally do there is a tone in here that is not unfamiliar in a way. I don’t know. It’s weird. It is this funny kind of…I’m just recognizing how much you can’t get rid of yourself. So, the idea of trying to, you know, you hold on to the ego and say this must be my work. Its just like even if I don’t want this to be my own work I am in it.

JN: There is almost no self-reflexivity because you can pass it along. You say, “Take this, now it is your turn to take it and do something else with it.” Until you have it here in the space you don’t know. So you can have this moment of “huh.”

TD: Yeah, exactly. Huh, look what we did.

NC: I don’t know about you but I process that some of the beginning pieces…well, I think the work has really changed over time. I think some of the beginning pieces, I feel that they are much more “this is how I would solve a piece and this is how Taylor would solve the piece.” But I think some of the newer ones are definitely moving towards a different space.

TD: And I did do that and you did solve that. And I think that for me in the beginning it was trying to see…and actually thinking how much of myself can I let go here. Not thinking consciously but thinking how much can I let go and still understand this. So maybe that’s why we are more present in how we would solve things because we were actually not able to let go of enough at that point.

JN: Have you seen a progression in your own work that is outside this relationship? You can’t help but be fed by your experience.

TD: I totally do. I have a totally different…

NC: Oh yeah.

TD: I don’t know if someone who’s seen stuff in my last show would have thought that but I felt really differently about it. I feel like my new work doesn’t look anything like Nicole’s. It doesn’t have to. The point is there is a certain, there are these moments where I say “I’m gonna do that.” I can just see her in her studio…

NC: There is a freedom.

TD: Yes, yes. Sort of like “arrrrrgg!” (laughs)

NC: Whereas I cannot, which drives me crazy! I don’t know if one’s good or one’s bad but (laughs)

TD: Different possibilities for completion. It’s like the door is wide open.

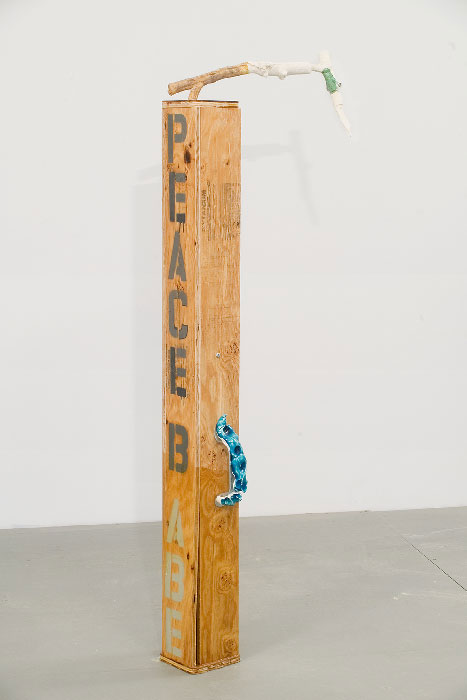

- Davis, Cherubini, Piece #1, plywood, galvanized steel, pencil, marble, ceramic, enamel, spray paint, graphite, polyurethane & MDF, 2007

- Davis, Cherubini, Roma, earthenware, glaze, luster, crystal blue ice, mirror, cardboard, watercolor-pencil, 2007

- Davis, Cherubini, Grey #2, pine, sycamore earthenware, glaze, epoxy, enamel, Medium-density fibreboard (MDF), marble, 2008

The List Visual Arts Center at MIT

"Davis, Cherubini, in Contention" is on view February 6 - April 5, 2009 at The List Visual Arts Center.

All images are courtesy of the artists and The List Visual Arts Center.