The artistic kinship between Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) and Arthur Dove (1880-1946) is the subject of a luminous exhibition,Dove/O’Keeffe: Circles of Influence, recently on view at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown as well as a superb catalog that reproduces the works on view. Both were developed by independent curator Debra Bricker Balken, who in 1997 organized a Dove retrospective shown at the Addison Gallery of American Art and the Phillips Collection.

While rarely in each other’s company, Dove and O’Keeffe shared a mentor—Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), photographer and evangelist of American Modernism—and a profound aesthetic connection.

Inspired by Dove’s pioneering abstractions early in her career, O’Keeffe began creating images that, like his, merge Modernist impulses of abstraction and distillation with sensuous immediacy. While gaining far more renown than Dove during her long life producing iconic, semi-abstract paintings of flowers and southwestern landscapes, O’Keeffe always regarded him as pivotal to her career. The radiant works selected by Balken show how the two friends evolved as artists in disparate ways but with a shared aesthetic instinct.

Dove’s works showed the young O’Keeffe, fresh from the Midwest, a way out of her stifling academic training that had more appeal than what she regarded as the overly cerebral trends prevailing among European modernists.

By 1912, Dove had already presented his first solo show, at Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 in Manhattan. Although regarded as the first works of abstract art by an American, Dove’s early explorations of form and color retain the presence of nature. In fact, the inner radiance of nature is his true subject. Even at their most abstract, Dove’s images possess a tactile sense of earth, sky or sea.

Decades later, O’Keeffe told an interviewer, “I think it was Arthur Dove who affected my start, who helped me to find something of my own.” In 1916, she began showing her first abstract watercolors at Gallery 291 and joined the circle of artists nurtured byStieglitz, whom she married in 1924.

Presenting works from all stages of their careers, Balken organized both the exhibition and catalog to suggest the two artists’ correspondences and mutual influences. Like the exhibition, Belkin’s catalog essay begins by putting them in the context of early Modernism in New York. Among the archival materials on view in the exhibition was the seminal tract by abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art. O’Keeffe owned a copy of the book, which advocated art as “an expression of a slowly formed inner feeling” rather than the observed world and theorized on the interrelatedness of painting and music. Also on view was the book by Chicago art collector Arthur Jerome Eddy, open to the image that introduced O’Keeffe to Dove—his pastel,Based on Leaf Forms a swirling Cubist composition.

Dove spent his life creating a new visual language with the power to express his profound connection with nature and his charged, exuberant world. Not content to paint what the eye alone could see, Dove pioneered his own kind of sensuous abstraction to render the moment-to-moment mutations of light, weather, and even sound. Distinctly American in their Emersonian reach for transcendence through mystical experiences of nature, Dove’s images reflect his childhood in upstate New York and years of farming and sailing along Long Island Sound.

Still, Dove was no recluse. He was alert to the trends of his day, a time when Sigmund Freud, Henri Bergson, and Albert Einstein were opening new vistas into the physical and psychic worlds. “The reality of the sensation alone remains,” Dove said. “It is that in its essence which I wish to set down...but simplified in most cases to color and force lines and substances.”

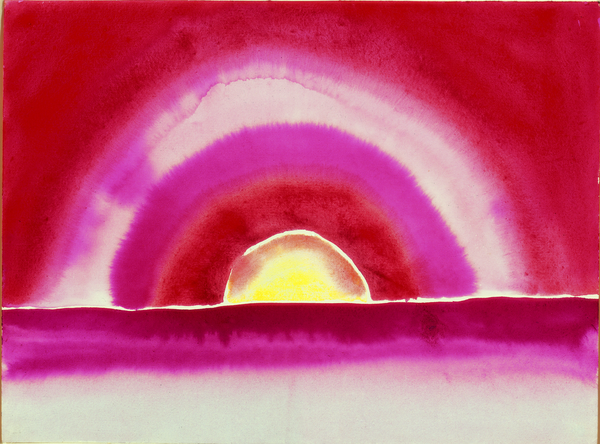

The works on view show his resplendent success—and the expressive powers O’Keeffe unleashed in herself by exploring her own vein of earth-rooted abstraction. Paired in the exhibition as well as in the catalog are O’Keeffe’s Sunrise (1916), among the works Dove described as her “burning watercolors;” and Sunrise I (1936), a tempera by Dove that glows with ecstatic bands of color. Among the oil paintings paired in both the book and gallery to thrilling effect are Dove’s Fog Horns (1929) an oil pulsing with sound waves of paint; and Dark Abstraction (1924) by O’Keeffe, an oil that evokes the organic motion of lava on rock; and Dove’s rapturous Sunrise (1924), which appears alongside O’Keeffe’s elegant, Art Deco image, Red & Orange Streak (1919).

Some of Balken’s juxtapositions suggest divergences between the two artists as well as their convergences. By the ‘30s, O’Keeffe was moving into more representational painting and Dove was making increasingly abstract images. A revelatory pairing of two large oils places O’Keeffe’s voluptuous Dark Iris No.2 (1927) next to Dove’s powerful Sea Gull Motive (Sea Thunder or The Wave) (1928). O’Keeffe’s semi-abstract image plumbs the core of a flower, using smooth brushstrokes to create bands of color that seem lit from within. Dove’s oil goes further. He contrasts smoldering silver light with thick black clouds, crossing his long, swooping curves of paint with short, feathered brush strokes that add tension, evoking the reverberation of sound. Dove’s painting is a synthesis of light, movement and sound.

- Georgia O’Keeffe, Sunrise, 1916. Watercolor on paper, 8 7/8 x 11 7/8 in. (22.5 x 30.2 cm). Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth © 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

- Arthur Dove, Sunrise I, 1936. Tempera on canvas, 25 x 35 in. (63.5 x 88.9 cm). Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein Courtesy of and copyright The Estate of Arthur Dove / Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

- Arthur Dove, Fog Horns, 1929. Oil on canvas, 18 x 26 in. (45.7 x 66 cm). Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Anonymous Gift, FA 1954.1 Courtesy of and copyright The Estate of Arthur Dove / Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

"Dove/O'Keeffe: Circles of Influence" was on view until September 7th at the Clark Art Institute, located at 225 South Street, in Williamstown, MA.

All images are courtesy of the Clark Art Institute and loaning institutions.