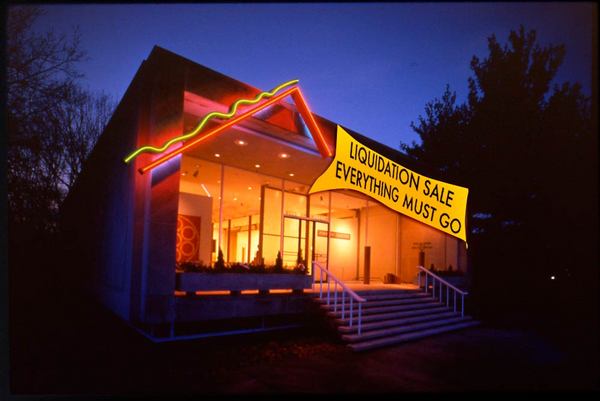

BACKLASH TO BRANDEIS CLOSING THE ROSE

On Monday, January 26th, The Boston Globe's Geoff Edgers broke the story that Brandeis University was planning to close down the Rose Art Museum and sell off the entire collection of 6000 works, including pieces by Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and Nam June Paik. The collection’s reported value is about $350 million. The move was a response to the growing financial crisis that is impacting Brandeis (and many other institutions) and was seen by critics as an ill-considered means to a short-term end that would ultimately undermine Brandeis in numerous ways. Adding insult to injury, it became clear that the university had not met with Rose leadership prior to the decision, and that no outreach had been made to the donors who had supported the Rose.

In the week since Edger's piece, there has been a flurry of activity. A petition, sponsored by "Concerned Alumni of Brandeis University" circulated. Students and Rose staff staged a sit-in protest on Thursday the 29th, and the Brandeis Faculty Senate has taken up the issue. The university was "condemn[ed]" by the Association of American Museums, and a group of donors and supporters of the Rose moved to block the sale of the works. Edgers and Greg Cook have both been tracking the daily changes in the situation, and we'll defer to them for specifics of the past week.

The long-term effects of this announcement are devastating, and will have long-term implications no matter how this turns out. Rose director Michael Rush has already said as much, both in his speech during the sit-in protest and in an email to supporters. Here, Rush points out the fundamental problem now faced by the Rose: even if the museum remains open, it will be crippled and unable to function for the foreseeable future.

In his email to supporters, Rush writes:

My deepest feelings go out to my glorious staff who cannot bear the thought of working toward dispensing this collection and who, like so many others, are now faced with unemployment, and to the Arts faculty (history and studio) whose credibility is now tainted and darkened in their professional world. What students who really care about art will want to come here? Would you? What new potential faculty member of merit would want to work here? There is no way to say the university is still devoted to the arts. It isn't.

That Brandeis has handled this poorly is not in question. How they will recover from this blow to their public image is hard to imagine, since (as Rush points out) they have now created the perception that donating to Brandeis is a risky venture. If the university is willing to sell off a major collection of artwork to meet a budget gap, who in their right mind would want to donate artwork to them? Or, for that matter, why would anyone donate to the library if their study collection could be liquidated? Why would someone fund the building of a new theatre that might be demolished or sold to raise cash?

One can only hope that other institutions around the country that have been considering similar moves are watching this unfold and reconsidering their plans. Brandeis took an all-or-nothing approach that has angered a large number of people whose support they need and cannot afford to alienate. Their method was even clumsier, making the decision without even discussing the plan with the museum director or its staff.

In preparing for this article, Micah Malone pointed out that "[...] 'this economy' seems to give people reason to do what they have wanted before, but didn't have the public leverage. in 'this economy' leverage/sympathy is at an all time high for assholes to get away with unpopular shit." There is a lot of truth in that statement, and as this economic crisis drags on, more and more institutions will be looking to save money and bridge budget gaps. Some will choose to make drastic and long-term changes, such as Brandeis has with the Rose. The volume of the response, though, has clearly indicated that these types of changes cannot be made without public scrutiny, even with the current economy as justification.

In a form letter sent to all e-mailers with complaints about the situation, Brandeis President Jehuda Reinharz responded with some “clarifying” points, mainly that the Universities Board of Trustees is closing the Rose with great regret. Curiously, an awareness of the “legal requirements that must be met in order to sell artwork” and “the current state of the art market”, are stated to give the appearance of not only legal standards they plan to follow, but a certain market savvyness. In other words, rest assured art world of Boston, Brandeis knows how to make these sales count. How they count and for how much will be something to watch in the coming months.

What lingers in this entire outcry is the difference between legality and ethics. By the American Association of Museums standards, it is clear Brandeis is behaving unethically. Reprehensible by most standards, even insulting when they claim they are “not lessening [their]commitment to the creative and visual arts” However, some larger questions loom. If what Michael Rush states is true: That art cannot be treated as a liquid asset; then who exactly enforces this ideal? Thus far, it seems Brandeis might be able to do just that. The coming weeks and months will reveal if Brandeis’ actions are like a “junky who sells blood or organs to get their fix” or just unpopular, unethical, but legal maneuvering. The fate of the art object in University collections hang in the balance.