By MATTHEW NASH

I've been down this road before. It begins with the uncomfortable feeling of leaving culture you understand, glancing nervously at the rear-view mirror as it fades further and further behind you. Eventually, when the city and the suburbs fall away, there is nothing but the vast rural openness that comprises much of this country. It washes over you in great torrents: a tide of sweeping vistas and dying fields, of rusted tractors and crumbling silos, of hope and despair, and the only thing that one can count on in rural America: time.

In her brief artist statement for "Black Tide", Candice Ivy tries to sum up this feeling and what it does to a person. "Southern history is like a black tide, thick as mud, washing over its inhabitants," she writes. "The residue remains present in the land as well as in the psychology of every individual."

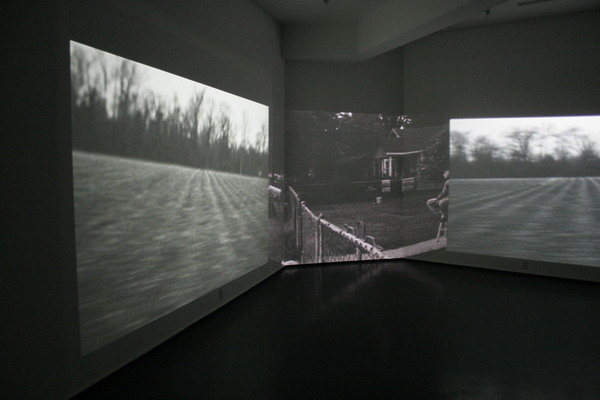

"Black Tide" is a 3-channel video installation prefaced by two drawings in charcoal of kudzu, the ubiquitous southern vine. These images offer a sense of what the videos provide: a density and a strangling pervasiveness. Without the context of the video, these images strongly reference Sheila Gallagher's smoke drawings from the ICA's Foster Prize exhibition. However, much of that similarity falls away upon viewing the videos, and Ivy's marks take on a darker and more ominous feeling.

Laconia's main room is oddly shaped, a truncated triangle similar to a baseball field. Ivy has used the space to her advantage here, putting the viewer in the middle of a trip away from the comfortable and deep inside her Southern world. On the left and right, flanking her main imagery, are shots from a moving vehicle of a furrowed field, forever rolling by. At times a train appears. Both of these clips loop, and neither stops moving, creating a strong feeling of motion, of descending into a world that is both rural and, given the darkly overcast and grainy nature of the film, forbidding.

The centerpiece of this triptych is a looped clip of several young men, perhaps in their twenties and probably younger, relaxing in a yard. The viewer is separated from these men by a chain-link fence, and through this barrier it is obvious that they live in poverty. The handful of visual clues offered by Ivy tell a lot about these subjects: their bare chests and cans of beer; the folding lawn chairs and patchy, untended lawn. Here, the element of time, created and enhanced by the constant motion of the framing videos, is reversed and made tangible. These young men are waiting for something, or nothing, or anything. Time is present, passing, and yet they stay still – even in the presence of so much motion and distance.

Only one of the subjects of Ivy's film addresses the camera, and it is a Pit Bull. This dog, often considered a beast of the lower classes, climbs up the fence between the viewer and the men, barking and pawing at the chain-link as it tries to get closer to the camera. The bark is not something we hear, as the sound in the room is reduced to a low undulating noise, like a passing train that has slowed down to a near-stop. Yet the dog continues to move toward the camera, its mouth open, the expression welcoming or dangerous, we cannot tell. None of the men move to restrain the dog, to save the camera, to do anything at all. Time passes only for this Pit Bull and no one else. The film flickers, and the loop begins again.

Candice Ivy has created a powerful and insightful installation in "Black Tide". It is dense and engaging, addressing both rural culture generally and her own native South Carolina with the kind of harsh glare that only someone who truly loves their home can cast.

- Candice Ivy, Black Tide, video installation (detail), 2007.

- Candice Ivy, Black Tide, video installation (detail), 2007.

- Candice Ivy, Black Tide, charcoal on vellum (installation view), 2007.

"Candice Ivy: Black Tide" is on view October 5 - November 23, 2007 at Laconia Gallery.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Laconia Gallery.