By STEPHEN V. KOBASA

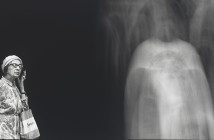

A festering of unnatural light around the corner from the exhibition entrance, the fluorescent wall is not glorious, but painful. There is no slant to the truth being told here; no "explanation kind," as Emily Dickinson would have had it.

The other end of the metal-panelled cube is interrupted by a cut out of a portal with a thin line of red incandescence just inside. Unknowingly disobedient, entering, I slammed my knee against a bench hidden in the dark. The video was just coming to an end and the illuminated sign had been meant to warn me.

We are always being warned by Alfredo Jaar.

Biography as sculpture, the story is told here of Kevin Carter, photographer and suicide. At the center of the matter is a single image taken by him in the Sudan during the famine year of 1993. The paradox in writing the review is how much of the secret to keep about what that photograph depicts. To know what is coming - or not to know - give a difference to the waiting in the dark.

I knew, and waited for the picture to be shown, registering my memory of it against the darkness and the projected texts which describe it before it appears - and then vanishes in a slow moment.

Carter waited to click the shutter on this image. He hoped to see the wings of death's angel come to make the picture perfect. But he took what he could get.

And as we watch what he saw, there is a machine hum that underscores the silence in the room rather than breaking it.

We have all looked at horrors like the one we are faced with here, usually while at the breakfast table, but always in comfort. As the exhibit recounts the story of a group of South African photographers with whom Carter began his work, it is established that:

"They witnessed too many murders.

They survived too many murders."

So have we all. But our survival comes at a price.

We come away blinded, literally, realizing that the bright outer wall of the installation is the flash of the camera in freeze frame. And we are too late.

It is difficult to look at anything else in the exhibition, even Jaar's reproductions of seventeen covers from Newsweek magazine of the period from the beginning of the Rwandan genocide in April of 1994 to the first appearance of that story on a cover in August of that year. In between, the periodical pictured other more suitable deaths - Kurt Cobain , Richard Nixon, Jacqueline Kennedy, O. J. Simpson's wife. The irony of our indifference is rendered as a cliché which will inevitably be repeated.

The film Muxima - Jaar's travelogue of absences - with its amputee statues from a Colonial past , and six figures staring out to sea as if in vigil over memories of the Middle Passage - the vibrant music of the soundtrack can do nothing to erase all that we do not hear inside the bright box with that one photograph.

Whose silence is at issue here? And which? The silence then? Or the silence now?

In Carter's photograph, there is a child - a daughter - whose fate we will never know. And there is the photograph of that child now among the images held in trust for Carter's daughter, who survives him. Just one image among the millions licensed by Corbis and offered for sale. Jaar tells us that the horrors of our time will be fully recorded. He tells us that they will become commodities. He does not tell us that they will ever end.

- Installation shots from from Alfredo Jaar’s , The Sound of Silence, 2006

Center for the Arts, Wesleyan University

Alfred Jarr

"Alfredo Jaar" is on view September 14th - December 2nd at the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery, on the campus of Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Wesleyan University.