By JON PETRO

When is making art - painting in this case - a valid function of expression that acts as anti-art or anti-painting? This question, aside from being an entry-level reflection of 20th century French existentialism, also pertains to Don Hartmann’s current exhibition, "Heads & Tales," at MPG Contemporary.

An answer can be formulated from several different points of view; I’ll answer it pragmatically. Anti-painting will always exist as long as there is painting to rebel against. In fact, you can view anti-painting, in contemporary terms, as a style. There is a proud tradition of rebellion in painters throughout the history of painting: the French Impressionists rebelled against the Académie des Beaux-Arts; the American Abstract Expressionist had had enough of American social realism; the list grows with each passing generation.

Most recently you can find this succession of dissent in England with the art movement called "Stuckism," which is a group of British artists, founded by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson, rebelling against the Young British Artists. Stuckists prefer fugitive art over the commercialized and Saatchi-Gallery-type conceptual art, so it’s a noble idea that Hartmann is rebelling. In casual conversations with Hartmann over the course of a few years he has repeatedly stated that he is not a painter, but a sculptor. So why is Don Hartmann making paintings?

Don Hartmann’s history with the MPG Contemporary began with a “NEW ART” competition for emerging artists in 2005, resulting in the solo exhibition, "Paintings of Personality & Estrangement," later the same year. This is Hartmann’s second two-person show at the MPG. I am a fan of Hartmann’s earlier paintings from before his three years of tutelage under MPG proprietor Michael Price.

We’ve all heard those stories about signing a representation contract with a gallery and then everything changes, or maybe it’s just the simple fact that when I first became aware of Hartmann’s painting, he had just given up sculpture and had no experience with the medium of paint. In fact, painting only becomes difficult - or a challenge - to an artist when he or she actually figures out how a great painting is made. From that point on it’s not about being an outsider, conceptual, or even post-modern artist. It’s about being a painter.

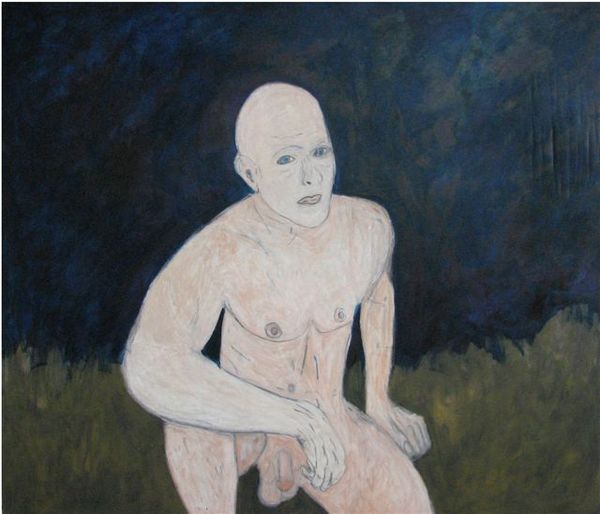

Style is regularly referred to in terms of how paint is applied to a canvas, or in this case, Hartmann’s wood panels. The initial quality in his painting is an angst-ridden, youthful sense of draftsmanship similar to what you’d find in a young high-school boy’s notebook. Hartmann’s paintings speak more to a quality of black magic-marker outlines, rather than to the richness of oil paint or in any tradition of rendering three-dimensional spaces.

It’s hard not to compare the composition of “Burnt Toast” (oil and acrylic on panel, 48" x 48", 2007) to any Impressionist painters’ technique of closely cropping a painting’s subject. Hartmann places a female figure just right of center, her face and eyes occupy the top right third of the picture plane with her eyes leering out to her left, far beyond the viewer. Her club-like right hand extends out, holding something that may be an oven mitt, while the edge of the painting crops the mitt’s edge. The figure is dressed in a see-through teddy that reveals her two black-outlined red nipples. I suggest Hartmann added this detail to imply some form of sexual tension, but it comes off as cheeky. The painting’s real tension comes from the figure touching every edge of the picture plane. This simple compositional device is what is truly interesting in this painting. It leaves the viewer no other choice but to have to deal with the painting’s image, however garish it may be. As for his use of color: Well, flat color never hurt anyone, but it’s not Hartmann’s strongest suit. You start to see a very plastic sense of color, but his palette is constantly muted or muddy, which, in my opinion, is holding the work back from greater appeal.

The least austere interpretation is that Hartmann is playing the quasi-outsider card, which is fine but only can be taken so far. Art history has shown us that outsider art stays outsider art. The stylistic narrowness of outsider art hasn’t stopped the commercial fine art world from taking the term and turning it into a cottage industry for everything imaginable - which is twisted enough to earn my suspicion. I would never refer to outsider art as a mainstream art movement or a genuine art phenomenon; however, there is an annual Outsider Art Fair in New York. So just how outside is that?

Personally, I’m weary of artistic labels, oftentimes finding myself at odds with an art world that is infatuated with the idea of style. Shouldn’t the viewing public be demanding substance over style? The one thing I will say about "Heads & Tales" is that it’s not the product of someone who is unaware. This leads me to consider that Hartmann, after three years and as many commercial exhibitions, is no outsider.

- Don Hartmann, Local Mower, Oil and Acrylic on Panel, 2007.

- Don Hartmann, New Budds, Oil and Acrylic on Panel, 2007.

- Don Hartmann, Burnt Toast, Oil and Acrylic on Panel, 2007.

"Heads & Tales" is on view insert date at MPG Contemporary.

All images are courtesy of the artist and MPG Contemporary.