By MONICA MCFAWN

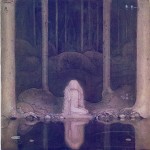

When I was a child, I remember being read "In the Troll Wood," a strangely compelling picture book. Its characters were trolls, fairies and princesses--not exactly the most original subjects for a children’s book, yet there was something so bewitching about the book’s images that even as an adult I can still picture my favorites: a dark mountainous troll with a glowing fairy in his hand, a princess captured and ogled by trolls who looked upon her with a befuddled fascination that was neither threatening nor completely benign.

Too often, things we love in childhood look silly or diminished when we see them in adulthood, so I was pleased to discover that the images had lost none of their power when I recently revisited the book. The illustrations were done by John Bauer, a Swedish illustrator from the early 20th century. Many of the images stand up as fine art--compositionally adroit, the imposing sense of scale and use of dark is reminiscent of Goya. And like Goya's work, they contain a great deal of ambiguity and menace. The trolls, princesses and fairies seem both empathetic and sinister, and the heaviness of the landscape renders them equally oppressed. They do not look meant for children.

Bauer's work, coupled with the ever-present debate about what's fit for children's consumption, got me thinking about the place of good art in children's lives. When people talk about children's media, there is an inevitable tension between the desire to preserve children's innocence and the need to expose them to the reality they must eventually face. The New York Times recently blogged about how old episodes of Sesame Street now come packed with a warning: the show’s openness about inner city poverty and depression might be "unfit for today's toddlers." Children need to be protected, but determining what they need to be protected from is endless fodder for moral debates. Is it sexuality? Homosexuality? Violence? Depression? Bauer’s renderings of trolls and fairies, however, seem adult not because of any morally questionable content, but because of how aesthetically sophisticated they are.

But my great interest in them as a child is at least anecdotal evidence that perhaps they were suitable for children. There is real reason why good art would resonate with children, and perhaps correspondingly there has been increased respect for the work of children’s book illustrators. The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts is devoted solely to art for children, and theR. Michelson Gallery in neighboring Northampton has an ongoing exhibition on children’s book illustrators like Maurice Sendak and Dr. Seuss. But whether or not children’s book illustrations should be considered fine art is secondary to what good art--whether it appears as illustration or in its traditional fine art formats--might uniquely provide children.

Good art, in its embrace of ambiguity, prepares children for the uncertainty and paradoxes inherent in real life. The mingling of sublimity with the quotidian, the absence of moral poles (Bauer's characters, for instance, seem both good and bad at once), and the general room for interpretation all offer children a primer for the indeterminacy of real life. This reality is arguably more "real" than simply showing children images of the adult world. Sexuality, depression, poverty and other "adult" subjects are difficult not just because of the problems they directly create, but because of the uncertainty and ambivalence that surrounds them. Great art, while it may or may not depict these subjects, at least provides training for the confrontation of the ambiguity each subject produces.

Art also uniquely nurtures children's independence. In general, children live in a binary and guided world. They are either catered to or they are shut out. Television cartoons and toys are specifically calibrated to entice them, and adults hunker down and talk to them in a tone both adoring and condescending. Adult media, on the other hand, seems foreign and forbidden - as excluding as their parents' closed bedroom door or whispered arguments. But unlike most of their world, art neither panders to them nor excludes them. Art does not tell them they can't enter and does not show them how they can. The sovereignty of art encourages the sovereignty of children by inviting them to find their own way in.

Great art solves the problem of impropriety because it both provides a primer for the real world while preserving children's innocence. Yet at the same time, art does not jeopardize that innocence. Art is one of the few things in life that doesn’t reward a jaded, "adult" worldview. You can’t "play the system" when confronting art because you can’t know it well enough. So much of its power and beauty is wrapped up with the unknown. If knowledge creates a loss of innocence, then great art, in its mystery, preserves it.

- John Bauer, Princess Tuvstarr, 1913

- Anderson Cooper (right), from Sesame Street, courtesy of CNN.

All images found online.