By DAVID O. AVRUCH

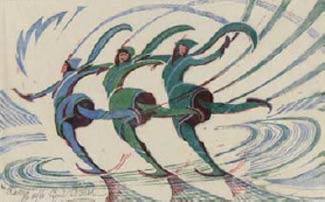

The 100-plus lithographs, drypoints, mezzotints, woodcuts and linocuts that comprise Rhythms of Modern Life: British Prints 1914-1939, at the MFA until June 1, are labors of love. For example, producing a linocut with four colors meant hand-carving four linoleum blocks, flawlessly alike except where the colors weren't supposed to overlap, with positive and negative spaces - since it was a print - rendered inversely. Any imprecision meant an offset lineup, like the newsprint bleed of Sunday comics. In most of the works, this intense exactitude belies their subject matter: Speed! Dynamism! Mechanization! Or in other words, modernity!

The influence of Italian Futurism is evident in almost every piece in the show. Launched by poet/haranguer Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909, Futurism, an extension of Modernism and adaptation of Cubism, initially sought to liberate young Italian painters from the shackles of their artistic past so that they too could be Modern. "And what is there to see in an old picture," Martinetti declaimed in the movement's first of many manifestos, "except the laborious contortions of an artist throwing himself against the barriers that thwart his desire to express his dream completely?" He goes on, "We affirm that the world's magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car ... is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace." Fair enough; however, the movement's other underpinnings, including misogyny, aggression and a glorification of war - "the world's only hygiene" - led to Futurism's concomitant identification with Fascism. Some historians even credit Futurism's bellicose jingoism with swaying Italian sentiment in favor of involvement with World War I. (The manifesto is incredible in its vainglory; read it here)

But anyway, back to Speed! Motion! Machines! Before long, the British, who were longing for a Modern art to call their own, jumped on the Futurist bandwagon, which is where Rhythms of Modern Life picks up. This expansive show examines the prints of London's Grosvenor School of Modern Art, focusing on Claude Flight and his followers, Cyril Power, Sybil Andrews and Lill Tschudi, as well as other contemporaneous printmakers. The show is organized thematically - rather than chronologically - into groups such as "Entertainment and Leisure," "Urban Life/Urban Dynamism" and "World War I" while fabulous racecars, elevators, windmills and dirt bikes populate the walls in various levels of stylized abstraction.

For example, in Sybil Andrews' The Gale of 1930 (part of the "Natural Forces" group), a color linocut in black, blue and white, two figures walk with the weather at their backs. Wind and precipitation, represented by negative space and dotted blue lines swirling around and under them, create perfect crescent moons out of their umbrellas and blown-up raincoats. This circularity is reflected in the curvature of the ground and visible beneath their oversized, outstretched legs. Meanwhile, the blue sky reaches down in rounded spikes, nearly touching point to point the tip of the black raincoat of one of the figures. In this work, humans are cogs in the machine of nature, and we are less concerned with the figures' experience of the weather than their seamless integration into it. Man's insignificance before nature is one thing, but the degree of stylization here implies a larger scheme independent of any deity. Andrews is projecting contemporaneous utopian (or perhaps dystopian) ideals onto the natural realm: the figures, whose only visible skin is their pointed chins and fists that grip umbrella handles, are dehumanized in this stylish world.

Also featured in Rhythms of Modern Life is Vorticism, the short-lived (ca. 1914-17) spin-off of Futurism that comprised the first British art movement of the 20th century. Taking Futurism to the next level, the Vorticists envisioned an ideal fusion of man and machine; unfortunately, the Great War not only killed off some of their supporters but also demonstrated what technology was actually capable of. It's interesting to contrast these pieces with the less abstract, Futurist-inspired work that came afterwards, as though the artists took a step backwards toward a more flexible, comfortable paradigm.

Despite the fact that all of the pieces in the show are heavily idea-based and these underlying concepts seem quaint to our sophisticated postmodern sensibilities, it is nevertheless fascinating to observe the ways in which changing technologies captivated and influenced these artists. Rhythms of Modern Life depicts a time when a group of artists shared a somewhat unified artistic and social vision, and it is for this reason, beyond the accessibility, sharpness or old-timey-ness of the images, that nostalgia emanates from the gallery walls.

"Rhythms Of Modern Life: British Prints 1914 - 1939" is on view January 30 - June 1, 2008 at The Museum of Fine Arts.

All images are courtesy of the MFA.