Entering a small constructed space we encounter a work from 1994 “The Wise Man Learns from the Spider How to Spin the Web,” by the artist, Huang Yong Ping, who was born in rural Xiamen, China, in 1954. There is a small, simple writing table with several Xeroxed copies of texts in Chinese with images by Marcel Duchamp. Suspended above is a cone like structure with thin ribs covered by metal screening. Inside is a low wattage bulb and, at the bottom of the fixture, a transparent plastic bottom on which a tarantula is observed. There is a trap door carefully concealed by which the spider is removed or fed. The lighting casts an elaborately patterned shadow on the surrounding walls creating a soft and meditative mood. A visitor could not resist the urge to reach out and pick up one of the pamphlets; perhaps with an intention of getting some further understanding of the work. Presumably, he did not recognize the reference to Duchamp and what that might mean to the artist.

This, quiet, contemplative room was emblematic of many of our encounters with this powerful, insightful and daunting exhibition by one of several among a phenomenal generation of Chinese born artists. Last year, Mass MoCA mounted a major exhibition of work by Cai Guo-Qiang. This is the first solo museum exhibition of Ping but he has previously been included in two group show at Mass MoCA. In its press materials, the museum implies that it will continue to present work by contemporary Chinese artists. Ping traveled to Paris, in 1989, to participate in a now legendary exhibition “Magiciens de la terre” at the Pompidou Center curated by Jean-Hubert Martin. Because of the events of Tiananmen Square that occurred while in France he remained and is now a French citizen. Other prominent artists of his circle include the late, Chen Zhen, who was presented in a stunning retrospective seen here at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Xu Bing, the subject of a major installation at Massachusetts College of Art, and Gu Wenda.

What is most compelling about Ping, and the other major contemporary Chinese, avant-garde artists, is the manner in which they are deeply rooted in their indigenous Taoist culture, and yet, hip to, and playful with the Dada traditions of the absurd and chance operations that were initiated by Duchamp, an enormous influence on this group, and then played out through the chance operations of John Cage, who, like Ping used the I Ching and its hexagrams as a means of determining the elements of his creative works. Ping is showing a series of paintings determined by chance operations. They could not be understood without a reference to Cage. Ping also makes strong and respectful references to the German artist, Joseph Beuys. A compelling work from 1991 is “The First Phone Call to Joseph Beuys After His Death.” At Mass MoCA works by Ping share a large gallery with an ongoing installation of a major piece by Beuys.

As Ping manipulates along an axis between Dada, the Western avant-garde, and the spirituality of Taoism, we are lured into a conceit that perhaps we understand the work. There is the false sense of security of knowing the works of Duchamp, Cage and Beuys, as well as, a sketchy overview of aspects of Taoism. But this is a deceptive approach. Yes, we may know, something about the work, and its embedded meaning, but, one senses that a deeper understanding is far more complex and may not be possible. We should be satisfied with responding to this rich and evocative work and leave the matter of understanding to unfold in increments over time. As a neighbor of Mass MoCA, there is the wonderful opportunity to see this work on many occasions between now and the end of the exhibition next winter. One approach may be to take on separate aspects of it through repeated visits. This is surely one of the great pleasures of living next to a world class museum. It is precisely what one misses in one shot, brief exposures to important shows when one travels. Surely, this Ping exhibition will be challenging to live with an opportunity to become ever more embedded in the work. But not with some impossible ambition eventually of unraveling its many mysteries.

The artist references this conundrum with irony and humor. He conveys the notion that, arguably, it was as challenging for him, as an Asian artist with little academic exposure to Western ideas to come to grips with Dada, as it would be for a Westerner to fully comprehend Taoism. To make this point, in a witty work from 1987, he created “The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern Western Art Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes.” We see the resultant dried pulp which resulted from this laundering of disparate cultures. Instead of reading the two texts discretely the artist is inviting us to “read” the mulch. This may be an allegory of his experience of living and working in Paris as an artist of Chinese heritage. It is a wonderful image of the movement and dialogue about globalization. Those who travel the circuit of art fairs and biennials are exposed to an onslaught of global art. Again, just through frequency and familiarity, there is the temptation to feel that by this process we have some kind of Pentecostal ability to speak in tongues. This strikes me as one of the true dangers of the one world approach. That art and all that is unique and special about diversity of world cultures will get mushed up into a pulp just as in Ping’s washing machine of the heart and soul. It is better to hope that we can feel and respond to the Magiciens de la terre than to pretend to understand them. It is important to travel by day through other cultures but, at night, to sleep in our own beds. In the realm of globalization, however sophisticated, we are all tourists.

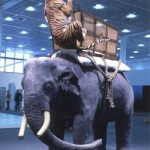

But what a wonderful journey Ping’s exhibition invites us on. There are so many incredible moments and experiences. The huge python skeleton hovering over our heads, empty tiger cages with their mangled bones left from a gnawing meal, crickets and lizards scurrying about in a turtle shaped cage, a life size sculpture of a tiger attacking an elephant. This last piece “Nightmare of George V” is a reference to the theme of Colonialism, in 1911 in India, when the King of England shot three tigers in a single day. The epic scaled, ongoing “Bat Project” which has caused political turmoil in its various configurations, documents a spy play downed after a mid air collision. It was stripped of it technology, cut up, and shipped back to the US. This is a diplomatic blunder that two super powers, struggling to find common ground, have struggled with and would rather ignore. The artist has continued to annoy all parties involved by keeping it topical. The installation of a section of fuselage with dead bats suspended from its ceiling is accompanied by a display of documents. It is one of those complex issues that one might plan to delve into during a return visit. And, what make of the enormous site specific piece, too fragile to travel, that is created by wooden forms into which is compressed sand, with a small amount of cement, to reference China’s era of crumbling colonialism. “Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank” is based on a Beaux Arts style bank building in 1920s Shanghai, the most Western of all Asian cities.

With time, the works of Ping have become ever more immense and complex. It is significant that Mass MoCA has presented the artist during a phase of his career when it is still possible to fit a selection of work within its vast space. With superb exhibitions such as this the museum is growing into its mandate. For some time it has been promoting its status, shared with Dia Beacon, as one of the few super sized venues for contemporary art in North America. But it is only with magnificent projects such as this that we fully understand just why bigger is better.

Links:

MassMoCA

"House of Oracles: A Huang Yong Ping Retrospective" is on view March 18 - February 19, 2007 at The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

All images are courtesy of the author.