There was a circus like ambiance last Sunday when I attended a spate of openings in a cluster of galleries at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut. I downloaded directions from Mapquest as it had been a number of years since last visiting the suburban museum to interview its founder, Larry Aldrich, in a profile for Art News. My intention was to support the artist, Damian Loeb, who was a part of three separate shows billed as “Homecoming” acknowledging three artists- Loeb, Sarah Bostwick and Doug Wada- who had grown up in or near Ridgefield. As a teenager, back in 1987, before dropping out of high school and heading for the city to live with a couple of friends including the musician, Moby, Damian had actually worked at the Aldrich.

For the past couple of years I have worked closely with the artist including regular studio visits whenever in New York. We connected after I reviewed an exhibition at Mary Boone Gallery based on details of movie stills. By the time we connected, however, he was leaving that phase of work behind and was moving on to a new approach of shooting his own digital images as a source for the paintings. At the time, he would explain, there were a number of collages based on classic contemporary films that were fully prepared to be finalized as paintings. A number of the works were even pre sold to collectors. And there was a thick stack of canvases in the studio just waiting to be painted. They were subsequently given to an artist friend. Damian was starting over in an entirely fresh and challenging new direction. There was no reason to abandon the movie stills, which were pre sold to collectors, other than to take on new, more daunting challenges, and to have complete control over the process of the work.

“There was nothing wrong with those collages,” he would explain to me. “And I would have enjoyed painting them.” But it was time to move on. Clearly, with considerable risk involved both aesthetic and financial. He was just getting out from under a burden of debt based on numerous law suits resulting from the appropriations of still photographs and news sources that comprised the earliest series that mostly resulted in infamy when they were shown at Deitch Projects. He would state that he never earned a cent from that early work, the sales of which, entirely went to settling litigation. But more than just wanting to move on from appropriation and its copyright issues Damian has always made it clear to me that it was just a transition to a time when he would create his own images. In the beginning, however, he knew nothing about photography and other media. Remarkably, considering such formidable accomplishments, he is an autodidact.

Over the course of the past couple of years, I periodically sat with him and viewed scores of images culled from thousands of shots that he had taken with digital cameras. Often, I asked if he would consider having a show of just the photographs. But consistently he responded that it was just source material for the paintings even though many of the images are stunning on their own terms. First and foremost, he is a painter but is also intensively exploring other media primarily on a need to know basis. He has a deeply rooted interest in all aspects of cinema. It has been a primary source for his imagery. Much of his visual thinking process is centered on film. He appears to view life through a lens. Currently, he and his British born wife, Zoya, are working on their second film script. During the opening she described how she was enjoying the challenge and hard work of conducting research at the New York Public Library. Beyond that, however, they are reluctant to discuss plans in detail out of fear of jinxing the projects. It is rather like when I asked Damian what he intended to shoot prior to a trip to Europe. Ever evasive and challenging, he replied that he had very specific ideas in mind, but if he expressed them beforehand, he wouldn’t have the drive to shoot those images.

During the studio visits, I have been attempting to get a handle on just where the images were headed. How were they evolving? Just what were the ground rules and parameters? Apparently, I am not alone in that inquiry. Eventually paintings have emerged. At this point, there are perhaps a dozen finished works. I have attempted to view and photograph them for my archives (they are all posted on the Loeb website). But they disappear quickly and appear to be snatched up by a waiting list of eager collectors. Accordingly, one question has been answered. The new works sell. Last fall, I was surprised to discover that he was working on a movie still. The large painting “Can’t You Take a Joke” is one of three canvases in the Aldrich show. Damian explained, at the time, that it had been sold based on the collage and that he had to deliver the picture which represents a tracking shot (much altered) from the John Carpenter film “Halloween.” As is always the case, the image is based on a blip on the screen and hardly a paradigmatic moment. Most viewers of the paintings would be hard pressed to name the movie from which the image is culled. My favorite, a masterpiece, is based on a dead animal in the road, a flash in Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.”

As much as he has discussed it in detail I have always wondered just how Damian culled, collaged and tweaked the sources that evolve into his paintings. The Aldrich exhibition “Damian Loeb: The Constructed Image, 1996-2006” precisely and brilliantly addresses that question. In a relatively small and concise project the curator, Richard Klein, has carefully selected and installed representative works, drawn from major phases of the artist’s oeuvre, and presented vitrines mounted on the walls with a range of collages and drawings. There is also a flat screen, wall mounted video monitor, that conveys vivid insights to the artist’s creative process. It is a truly fascinating project that greatly expands the dialogue about the artist who has all too often been pilloried by the gossip media and flogged by major critics who should know and behave better. After thoroughly trashing the early work, often conflated with misinformation about the artist’s alleged, fast lane lifestyle, the more knowledgeable critics and curators are gradually, albeit reluctantly, coming around to recognizing the formidable accomplishments of the artist.

Along those lines, I asked him what he calls the new series? “Genius,” is his surprising response. “If you title the show 'Genius' it's your best chance to have critics who hate you, involuntarily, to have to say something nice about the work. Which is at this point the only way I can get them to say something nice.” Damian, I was getting there, just give me a bit more time. Yes, there are elements of brilliance, but he is still a relatively young and evolving artist.

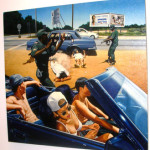

The revelation of this show was finally having the chance to view, first hand, one of his most controversial early works “Sunlight Mildness” from 1998. The painting, which depicts three youngsters enjoying a summer joy ride in a convertible, is appropriated from a book published by the photographer Lauren Greenfield. In the background Damian added a sub plot, not in her original photograph, depicting a brutal beating and murder. The protagonists, Damian himself, shirtless, with the ever present prop, a cigarette in his hand, baseball cap on backwards, his artist friend, Cecily Brown, in a halter top turned away from the action looking past us, and a third youth driving the car, seem oblivious to the event transpiring. Shortly after the painting was printed on the cover of Flash Art Magazine the photographer sued. Despite her protests about the encroachment on her art, arguably, it was all about money. At the Aldrich, the painting is displayed with an elaborate wall label which is precisely worded based on terms of the out of court settlement.

(As a postcript, during a follow up conversation with the artist after he read this piece, he has some clarifications. That the characters as depicted in the painting of "Sunlight Mildness" are literally modeled after the original source material, the photograph published by Greenfield. "That is not a self portrait of me or an image of Cecily Brown. They were meant to represent mindless kids who are self absorbed and oblivious to the horrific global events depicted in the background. There is a bit of the ass hole in me, like the kid in the back of the car, shirtless with his cap on backwards, but that character is not me. And in the original photograph the character smokes a cigarette. I agree with you about smoking and I would never attempt to glamorize it in a painting or any work of art. When Flash Art wanted it for the cover they asked if I would tweak the image and in that singular circumstance, yes, that is me, Cecily Brown, and John Currin is depicted as the driver. So you were a bit confused in the chronology of the story.")

In that phase of his development the artist was limited to cutting and pasting collages for his compositions. We see the accompanying working studies and process. There are overlays, traces, and drawings to work out the details which were then projected onto the canvas. At that point the artist was looking for sources of material to paint with some alterations. Nothing was ever literally copied; which would be a fair use argument if any of the cases went to court. But he learned from lawyers to settle and never get to court even though he would ultimately have a strong chance of winning. By then, they informed him, he would be flat broke. Which was close to the truth when he left Deitch for Boone.

Works such as “Sunlight Mildness” and others originally shown at Deitch Projects are problematic for reasons other than copyright infringement and resultant lawsuits. They represent the juvenalia of the artist and all too readily highlight sensational subject matter and the growing pains of learning to paint. Had the artist continued in this manner I would not have much interest in the work. Ironically, it is precisely from this point where the British artist, Damien Hirst, appears to have taken off with an exhibition of “paintings,” actually the product of a team of studio assistants, that emulated Loeb’s sensationalism. Knowing Loeb’s work in depth, there are remarkable similarities in a few paintings which appear to go far beyond coincidence. It was an issue which we discussed with intense passion at the time of the widely covered, and trashed, Gagosian exhibition. Ironically, the critics appeared to attack Hirst on the same grounds of gratuitous sensationalism that they laid into Loeb. Hirst might have been better informed by reading the clippings as well as looking at Loeb's vintage paintings.

Compared to the other two works in the Aldrich show “Sunlight Mildness” is not as well painted. The surfaces are hard and reflective. No light penetrates the surfaces which are membrane like and brittle. I asked Damian if the palette were different as there seemed to be a yellowish cast over the surface. “Cheap varnish,” was his initial response and explanation. During a later phone conversation he attempted to explain the less than ideal lighting of his old studio. He refuses to discuss or defend that early work. But he also stands by it. “Hey, I was how old at the time,” he asked rhetorically, “Like 28. Simply put I paint better now. My work has evolved. I was learning how to paint.” The cigarette in the hand of the “self portrait” in that painting also disturbs me. Too often cigarettes have been depicted as signifiers of hipness in paintings and film. Viewing the Munch show at MoMA, for example, one of the most famous and compelling self portraits depicts the artist exhaling a great romantic cloud of smoke. Or the great self portrait by Max Beckmann in the Busch Reisinger Museum which depicts the artist with a cigarette. No, I don’t think it’s cool. As a former smoker, I am concerned for the health of others, and Damian is a compulsive chain smoker. There are many social and political problems in the work of that period and some day I will pick through them when and if I can get Damian to cooperate. This is to say probably never.

But the important point is that on most levels he has come a long way from strident, sanguine youth. This show does a terrific job of tracking the giant steps. There are studies for an early work “Fish Sticks” one of the best of that period. It depicts a man looking in the fridge while a gorgeous nude woman, her weight thrust onto one hip, looks on enigmatically. Next to the original appropriation is a strange little collage assembled from several small Polaroid snap shots. Damian explained that there was something wrong with the source image and he needed to switch the figure but match the original pose and lighting. Often in his paintings he explained that he uses bits and pieces of material for different parts of a painting. Hence the collaging. At first it was cut and paste but eventually computers and Photoshop took over, and now, digital photographs.

The video monitor in this show has a wonderful animated sequence which demonstrates the many intricate steps involved in clipping and conflating found footage into a resultant still which is based on, but a variation of, the original. There is no single painting in the movie stills series which is a precise and verbatim copy of a blip in the original footage. That’s where the art, here we go, genius, is involved.

One wall entails a grid hung in parallel rows of large framed prints of the digital photographs which have been the source for the paintings of the past two years. They do indicate a certain trend. The resultant paintings are given titles referencing famous contemporary films. So there is still that cinematic context even though the images are entirely unique and original. There is also a preference for the noir. The mood is often of night, twilight and interiors of rooms, or looking out through windows. There are a few full sunlight outdoor paintings such as a sensual study of an adolescent girl in a bikini floating on a raft in a pool. Also, some underwater views, with a glimpse of bare breast or a well formed bottom knifing through the aqueous medium. Some are gleaned from the social occasions that he despises and often parodies. The painting he showed with Mario Diacono “Metropolitan” is one such example. In this show is “The Vanishing (SPOORLOOS)” a painting finished just a couple of weeks before the exhibition. It was one of my favorite photographs and I was pleased that it made it to canvas. The image is a low angle, night view of a fashionable woman’s legs haloed in the headlights of an oncoming car. It is redolent of irony and suspense which is an ongoing response to most of the works in the “Genius” series. The artist states that he plans to keep it for himself now that “I finally can afford to.” It is, in fact, the only work of his that he “owns.”

My greatest regret and concern is never having the chance to see all of these new works together. Six of them were shown and sold recently in Cologne at Jablonka Galerie. They are rapidly being dispersed into private collections. Next year, there will be a show of some of the works at Mary Boone in March. By then, we will learn whether the critics are willing to let go of the past and see the work for what it is. Not that Damian really gives a fuck.

Links:

The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum

Loeb & Moby image by the author.

Artwork images courtesy of the artist, White Cube, London, and the Rubell Family Collection, Miami.