My first reaction to “War Games”, an exhibit of photographs by Stephen Jacobs taken of WWII reenactors, was one of disorientation. I knew nothing of what the show was about when I first walked through, but I knew immediately that something about them was off. I was not entirely fooled into thinking these were true documentations of WWII. Nor was I convinced that they were not. In fact, I was most struck by how un-striking the photos seemed. They were, in fact, beautifully placid.

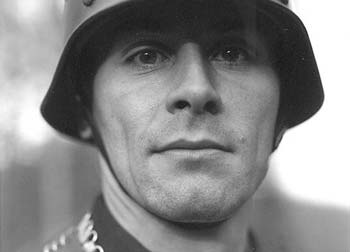

The people in the black and white photos are dressed in German WWII war gear, and stand beside trucks or bunkers, their belts full of accoutrements, their faces unsmiling, in a landscape of hazy forest. But their expressions are non-descript, and do not show any of the emotions I would have expected to emanate from actual war veterans. There is not happiness at the presence of a photographer, not anguish at the violence that surrounds them, not awkwardness or fear, or any such emotion that is associated with war. In photographic journalism, the men and women fighting do show emotion, even their smiles take on sadness, and even their fear is intertwined with anger, as they live all these strong feelings in tandem. Instead, the perfectly poised subjects of Jacobs’ photos look like unconvincing actors in an amateur playhouse. They fall short of evoking any sort of emotion, since the subjects themselves seem to be without emotion. And yet, the images are not devoid of interest, because it is just their placidity that gives them a puzzlingly ethereal, if unconvincing, quality.

So why the disorientation? Mostly, the people are incredibly clean. Whatever bloodshed, disorder, violence occurred during this war was, in these photographs, absent. The players, modern American men and women, perhaps are to blame for their portrayal of an idealized, horror-free, uber-romaticized version of one of the most horrific, world-changing series of events in modern history. The photographer exacerbates this, by taking dry, pleasantly constructed photographs completely incongruous to the disorder of war. It is as if everyone involved is staging a play- a play with no particular beginning or end, and without an audience, save for themselves.

The care of the clothing and accessories and landscape, the trucks and the bunkers, is meticulously accurate. Given this evidence, as well as the myriad of internet sites selling WWII paraphernalia of all types, my idea is that the main focus of the reenactors is not the event itself, but the aesthetics of it. Having been an employee at the Renaissance Faire in my high school days, I am well aware of the attention paid to authenticity in skirt, in bodice, in speech, in action, and these thoughts were foremost. Behind the curtains were generators to make that authentic shepherd’s pie, and a large sign saying privies actually held rows and rows of stinking plastic port-a-potties. Thus, our group reenactment gave us an “authentic” arena to live out historical fantasies or ideals. But the real and the unreal can inevitably exist in these reenactments in such close proximity, that it is impossible to separate one from the other, and we are misled to believe that all of it together is “authentic”. In recreations of the past, there is only so much that an individual can let go of, and only so much that he can ultimately take on. Even if participating in these events becomes, for a fanatic, a yearly occurrence, a weekend occurrence, in the end that person has been raised a certain way, socialized a certain way, and is ultimately a member of contemporary society, and no matter how many layers of “authentic” wool clothing, still possesses contemporary views. In the end, all the war reenactors climb unhurt out of their barricades and get in their cars to drive home and take a nice hot shower.

But, the question of authenticity still presses. If the earliest war correspondents staged their photographs, and the practice was prevalent in WWII, how do we resolve the idea of authenticity in Jacobs’ photographs or in supposedly truthful photos of actual wars? If both are staged, perhaps Jacobs is the more honest man, because he does not pass off his photographs as truth. Susan Sontag wrote, “What is odd is not that so many of the iconic news photos of the past, including some of the best remembered pictures of the Second World War, appear to have been staged. It is that we are surprised to learnt that they are staged, and always disappointed.” (1) We feel cheated when we expect the truth to be documented, and then find out it is staged. Still a discussion could continue on the appropriate definition of truth, and whether or not truthfulness can be observed and valued in a staged image, or if an impromptu image is less of a liar.

Jacobs saves us from this discussion by circumventing this issue entirely, by describing his photographs as bringing the level of the authenticity that interests the reenactors full circle. He does not try to pass off his work as a true representation of an actual war, but instead lets his photographs become, as he, dressed in the proper attire of a WWII war photographer becomes, part of the pageantry. He strives to be authentic only in giving the reenactors documentation of the events they participate in, and to be a player himself by taking on the affected part of "war photo-journalist”. His goal is merely to add to the affected realism of the participants; black and white journalistic-style photographs were a product of the actual war in the 1940’s, he provides this same style of product to the reenactors as an added element of realism in the play. He himself is part of the play, and his photos no more than the product of his participation. Jacobs is clear that his photographs do not document the Second World War, his photographs document WWII reenactments.

The juxtaposition of Jacobs’ work with that of the other artists in the gallery presents an interesting mix: all on the surface are quite different, all relate to time. Each in its way seeks to recapture the past, thus examining our identity in the present. Who are these time travelers who live their weekends and vacations in the past? And why choose a past with so much drama and pain and loss? Is modern life too devoid of spectacle and authenticity of emotion? And if the quest is for authenticity, why is the product of it so lacking in truth?

Unfortunately, for someone who has no relationship to WWII reenactments, though the arising questions are interesting Jacobs’ photos are subsequently boring. Only two capture my attention: One, of a man’s hands holding a 1940’s passport. The passport is real. Two, of an older man kneeling at a bunker, half-turned towards the camera, an expression of surprise on his face. This is one of the only photographs not staged, and one of the only ones with a captivating expression. What is it that captivates my attention in these two images, and only these two? Is it that I can finally see a reflection of myself in the people involved? Or that the photographer is leading me to something of more depth than the close-up of a man pretending to be of a different time and country? And why is that not captivating? Because he is closed from me, he is in his own world, in a pocket of Pennsylvania, in 1945, in the middle of his own idea of WWII, somewhere in his mind.

_

(1) Sontag, Susan, “Regarding the Pain of Others”, Ferrar, Straus and Giroux, NY, 2003.

- Stephen Jacobs, Musketeer in Machine Gun Nest, Newtonville, PA, 2004

- Stephen Jacobs, 90th US, 2004

- Stephen Jacobs, Feldgendarme, Annvile, PA, 2004

Links:

Gallery Kayafas

"War Games" is currently on view insert until February 26th at insert Gallery Kayafas at 450 Harrison Ave., Boston.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Gallery Kayafas.