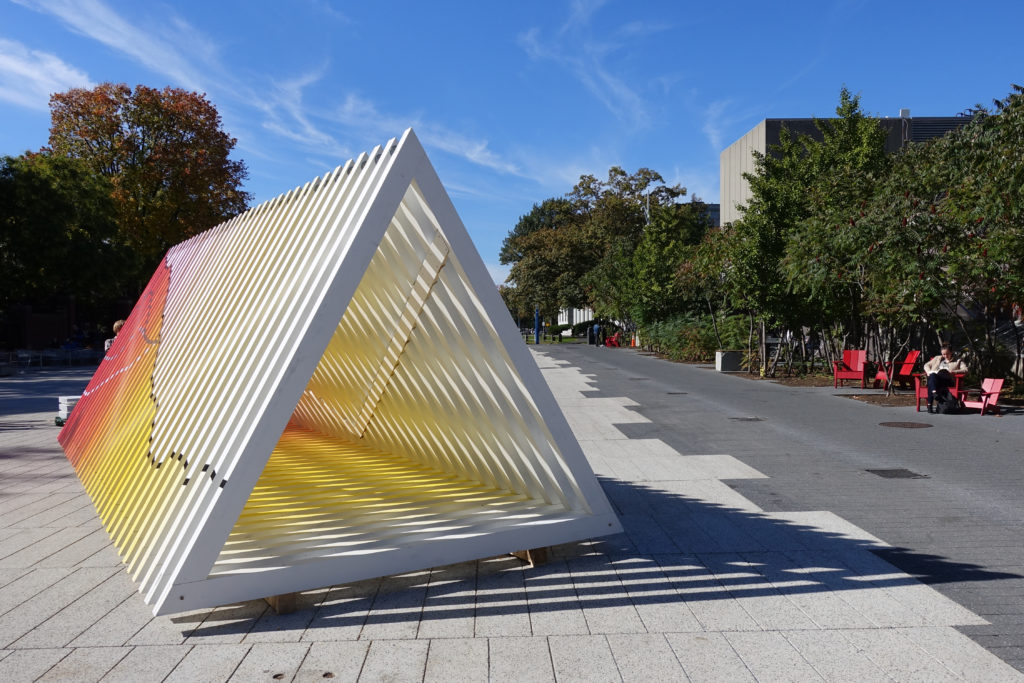

Artist David Buckley Borden and Harvard Forest Senior Ecologist Dr. Aaron Ellison, along with an interdisciplinary team of scientists and artists, created Warming Warning, most recently on view on Harvard’s Science Center Plaza, to place climate change data in the public forum. During its time on the Harvard campus, it asked visitors to examine both the collective and individual roles in this crisis.

After its six-week run at Harvard, Warming Warning moves to a new yet familiar home near the Harvard Forest. The work was constructed from wood harvested and milled by the Harvard Forest Woods Crew and framed by local timber framers. The human-scale, three-dimensional sculpture invites curious visitors to slow down, circle, and ponder, containing graphics about global temperature data and potential scenarios of carbon dioxide emissions. On the heels of a number of alarming scientific reports and media articles, Warming Warning enters the conversation at an opportune time to spark thoughtful dialogue locally. I spoke with David and Aaron during Warming Warning’s last week on campus to learn more about the origins, goals, and results of the project.

Karolina Hac: How did this project come about?

David Buckley Borden: Warming Warning, in many respects, is a spin-off from the Hemlock Hospice project - part of the 12-month fellowship I did with the Harvard Forest from 2016-2017.

One of the projects we developed was Hemlock Hospice, which was composed of 18 stations or installations that made an interpretative trail exploring the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive insect. One of the critiques of the project, both from ourselves and outsiders, was that we had told the story and built awareness for the issues, but what would be the next step? And it was a great critique, but it was a little hard to answer, partly because there is no solution for that particular issue.

But we were interested in giving it a shot. So we said, ‘Let’s develop a piece that actually explores different options in which people can take action, but also is an accessible art and design piece.’ It’s not a strict data visualization piece, and it isn’t just a visual delight.

Warming Warning at Harvard University. Photo by David Buckley Borden

KH: What were some of the goals of the Harvard Forest in bringing this work to the Harvard campus?

Aaron M. Ellison: We wanted to increase awareness about climate change, how people initiated and hastened these changes, and what we can do about.

We also wanted to highlight the Harvard Forest, including its location on the landscape (most people don’t know that Harvard even has a forest, much less forest research, and that it’s in Petersham, not Harvard, Massachusetts); its long history of research on climate change and the interplay between people, land-use, and ecology in driving climate change; and its place in a national and global web of research about climate change.

Finally, we wanted to show that what we do locally (e.g., with climate change) can be a microcosm of what is happening everywhere in the world. We wanted to encourage thinking and responsible action about climate change, especially by Harvard staff, students (at all levels), and faculty.

KH: What was the process of creating this synthesis of art/design and science like? What was the starting point?

AME: [It was] collaborative from the get-go. We work together on all aspects of the project. This makes for a much more impactful and satisfying project than those for which scientists simply hand off the data to artists.

DBB: For Warming Warning, as with our other collaborations, we did not start with the data. We typically start with a concept centered on communicating science. Our intention is to tell a story. We bring in the data as much as it helps communicate the bigger idea. In fact, the first iteration of Warming Warning included different data than the final piece. The data is just one layer to telling the story. Forms, cultural references, visual experience, are just as important when it comes to creating an accessible art-based science communication piece.

The forms, colorways, and overall creative direction for Warming Warning was a continuation of our Hemlock Hospice design, but specifically applied to a global warming context. So in that sense, it was generally seamless. We have been working together for almost three years, so we have a practical understanding of what it means to be equal co-creators of interdisciplinary artwork. The conceptual process for the piece occured over the course of a week in December 2017. Throughout the following year we fine tuned the details and the construction plans as we worked with a structural engineer. Creating a public art piece for the University was a learning experience, however. It was certainly different than creating work for an art-based interpretive trail in a remote woods.

Detail of Warming Warning. Photo by David Buckley Borden.

KH: With its central location in the Harvard community, who was the intended audience?

DBB: We were interested in how to get student organizations involved. The university is large and seemingly disorganized, even with its allied efforts. The project was a unique partnership between the Office of Sustainability, Harvard Common Spaces - which programs Harvard’s public space - and the Harvard Forest. Each person brought something to the table, but the one thing everyone agreed on is we need programming to support this - which is something I’ve been pounding for seemingly decades.

KH: What was the benefit of joining together with people who may approach climate change and associated outreach differently than you?

DBB: The big outcome is not the art or design itself, but the opportunities the art creates, whether that’s through public talks or workshops or press relations. The Harvard Forest supports science and communication projects, and although [Warming Warning] can definitely be seen as an art and design project, at its core it’s a science communication project.

But the Harvard Forest realized strict science is not really engaging. We have the two data visualizations on the left and right - one shows the >1.5 degree Fahrenheit change (since 1880) in global average temperature, the other is future scenarios of carbon dioxide emissions - and an artist and designer, I think it’s interesting, but we knew we needed more than that. We needed to engage the people who don’t think they care about these issues in order to start these conversations. That’s why we put the effort into making it interesting - an optical art piece - depending on where you look at it, you get some interesting color patterns, shadows, and so on.

Warming Warning at Harvard University. Photo by David Buckley Borden

KH: Broadly speaking, what sort of reaction have you gotten from the public?

DBB: There are different layers involved, because it’s in this very public nexus. It ranges from the people who just pass by it to all of the student groups and organizations [on campus]. One of the reasons we did program beyond the campus was because although the original audience were the students themselves, the University is interested in engaging the larger community in which its embedded.

AME: Other users of the Plaza (including the seasonal Farmers Market) have noted that it brought more and new people to the plaza. The Harvard Facilities’ crews have commented that it’s one of the more engaging and enjoyable uses of the Plaza they have seen.

KH: Have there been any surprises along the way, in terms of public reaction?

DBB: One of the things that I’ve been surprised by is the range of responses - from total indifference to people who are so focused on the issue that they teach me about the data. For example, one day, a semi-retired physicist who works at the University walked by, and while he was looking at it just blurted out, ‘You know what this hump is?’ referring to the little hump in the temperature increase graph, ‘that’s World War II.' That’s evidence of a major, human-driven mobilization, and you can see the impact right one the map. To me, that’s brilliant in terms of narrative, because if we can make the hump go up, there’s nothing but political will to make the hump go down.

I was really surprised by the folks from the Graduate School of Education taking a keen interest in the work. We’re actually developing a special program geared just toward educators in which we talk about the role of art as a pedagogical tool for climate change issues. Some of the programming was conceived as we were creating the project, some of it has developed in response to the reaction to project.

KH: Considering the potential audience and the goal of public awareness, did you have any hesitation about putting the installation in a community where many people might already know about climate change?

DBB: At first I thought we were preaching to the choir. If I was feeling cynical, I would say, yes, it could be in a different location with more potential for impact. But part of me thinks, maybe we’re preaching to the concert, so to speak - an audience that is kind of self-selected. But even then, we all need to be reminded of these issues.

No matter where you put the piece, you’re pre-selecting your audience, and I haven’t figured out a response to that.

AME: Perhaps not surprisingly, even at Harvard, not as many people as we might naively expect know about or are aware of immediacy of climate change and the range of plausible scenarios to respond to it that are being discussed worldwide

KH: You approached this project with the idea that greater public awareness requires different types of programming. Can you talk about the types of programming you used here?

DBB: It was pretty broad, from working with educators - some are practitioners, some are theorists - to connecting to the Somerville [Museum’s Triple Decker Ecology], which is a community art show using art and design to talk about local environmental issues.

We want to have a big variety of program - not just the topic, but the place in which the program occurs. In many respects, it’s place-based outreach.

We kicked off the opening with a pecha kucha with ten different groups - some were student groups, some departments - and each group had five minutes to talk about how they were engaging in direct action with climate change on campus. You got a sense of the the breadth and variety in which people were addressing the issue.

Warming Warning at Harvard University. Photo by David Buckley Borden

KH: What about the Warming Warning’s goal of fostering direct action? Can you elaborate on what this means to you?

DBB: One of the big questions is how do you measure direct action? You have a sense in your gut that people are responding to it, or they’re not, but if they are responding to it, you don’t really know how.

Based on what I’ve learned from my work on the fellowship, which included doing research into what people do in terms of art-driven activism, and then the actual practice of putting it into action in the forest and here, we need a broader team with different experts at the table. For the next project, we’ll have to additional components [including]a social scientist and a policy group or an activist that have a cause and have the means and methods to measure the impact of the cause.

One of the things we’re looking at for future projects is developing two different installations and treating them as social experiments. You record people’s attitude before they experience the piece and then at the other end of the piece, they’re questioned again, which will let you measure if the piece is making an impact in terms of awareness levels and attitudes. That’s the next step - that’s where this needs to go.

Project Collaborators: David Buckley Borden, Jack K Byers, Mike Demaggio, Jim DeStefano, P.E., Dr. Aaron M Ellison, Dr. David Foster, Lucas Griffith, CC McGregor, Roland Meunier, Dan Pederson, Matt Robinson, and John Wisnewski.