The Firmament, the final exhibition at the Hood museum’s temporary downtown space, showcased Toyin Ojih Odutola’s recent portraits in oil pastels, charcoal, and pencil. Created between 2016 to 2017, Ojih Odutola portrays two Nigerian families: the UmuEze Amara, the oldest noble clan of Nigeria, and the Obafemi, an aristocratic house of traders and ambassadors. Both houses are adjoined by the marriage of their two sons, the Marquess of the UmuEze Amara house, TMH Jideofor Emeka, and his husband, Lord Temitope Omodolle of the House of Obafemi. The intro text of the exhibition is written by none other than the Deputy Secretary of the Marquess, Toyin Ojih Odutola herself, stating that the marriage of Lord Omodele and Lord Emeka has lent the Hood Downtown a gorgeous collection of intimate and private moments. The fictitious narrative in the show considers liminal spaces where colonialism does not interfere with the lives of Africans.

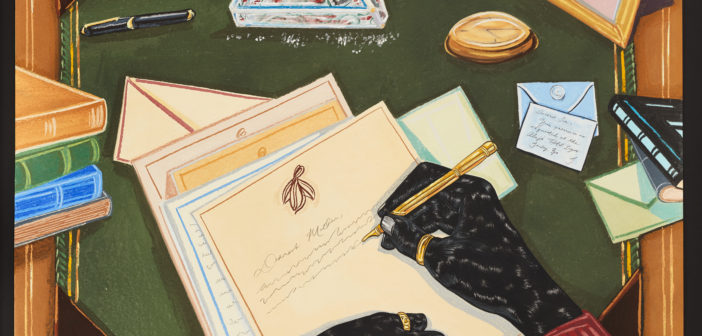

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Her Scarf, 2017 © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

The Firmament is defined as a tangible dome between the heavens and earth in the Book of Genesis. The firmament was created by God to divide the waters below; the firmament became Heaven, and the spaces that the characters occupy in the exhibition are as ambiguous as this concept of heaven. When I asked the artist about the geographical location of the figures, she explained that these spaces could exist beyond geographical sense. Given the absence of geographical specificity, Ojih Odutola orients skin as a topographical map using the color black and varying media techniques to expand on the aesthetic qualities of Blackness in the field of drawing. In establishing a language for skin, she explores themes of migration and national identity, all of which originate from her personal experience. Born in Ife, Nigeria, Ojih Odutola immigrated to Berkeley and later to Huntsville, Alabama where her father would work as a professor at the University of Alabama. While chatting with the artist, we bonded over the transformative experiences of becoming Black in the United States, a common phenomenon for Black immigrants in the diaspora. In this becoming, one’s ethnic identity is erased; one is not Igbo, Yoruba, or Swahili, but rather one’s Blackness becomes a monolith that conceals their inherent and varying identities. In this presupposed form of identity, Ojih Odutola has responded by conjuring Black and/or African figures that characterize and reveal the private and social life of the Black bourgeois.

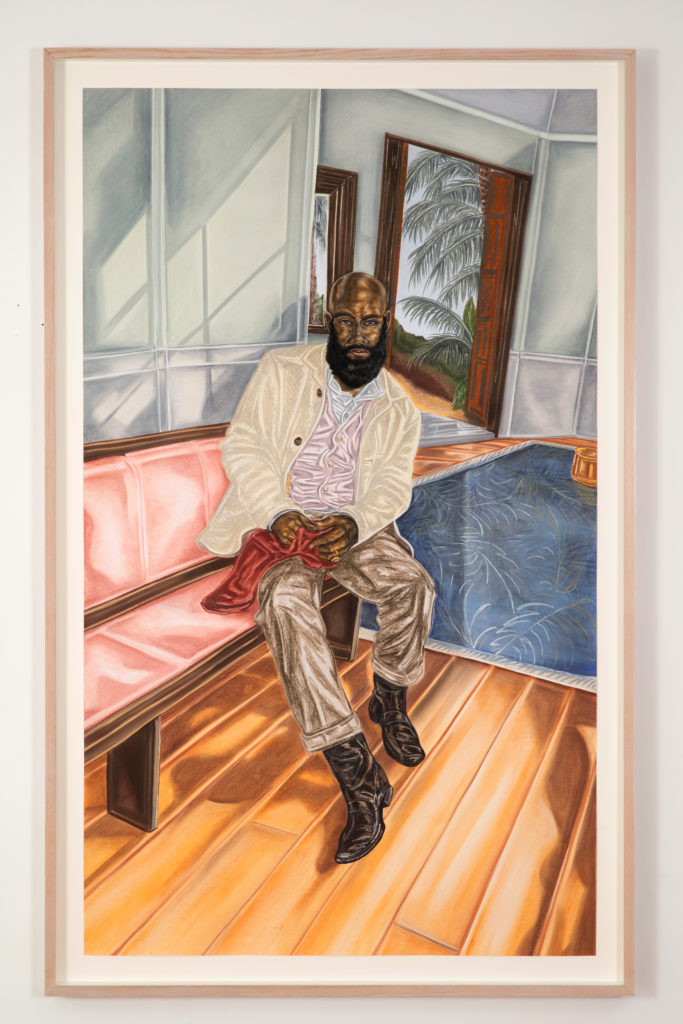

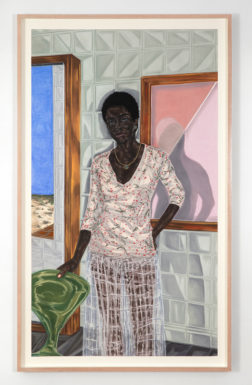

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Pregnant, 2017 © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Representations of wealth are displayed through the means of fashion and accessories such as veils, gold chains, and rings, precious stone earrings and necklaces. In Pregnant, a young Black woman dressed in a floral silk top and a transparent veil dress returns the gaze back to the viewer. We cannot identify her pregnancy as she poses calmly in an interior scene with a grey tile background and a glimpse of a semi-arid landscape scene. The color palette comprises of blues, whites, greys, pinks, and greens, and I was reminded of Georgia O’Keefe’s pastoral scene, Pelvis with Shadows and the Moon (1943). On another wall is Year Later - Her Scarf, a portrait of a bald and bearded man in a spacious grey room. Dressed in a beige blazer, brown pants and leather boots, he leisurely sits on a pink bench gazing at the viewer while clutching to a red scarf with a gold and emerald ring on his ring finger. Perhaps the two, in their extravagant fashions, are a married couple awaiting their unborn child. The aesthetic that celebrates Blackness vis-a-vis wealth, provokes two questions can social status emancipate Black people from the shackles of anti-Blackness? Is the Black bourgeois representative of the Black communities’ aspirations for self-determination?

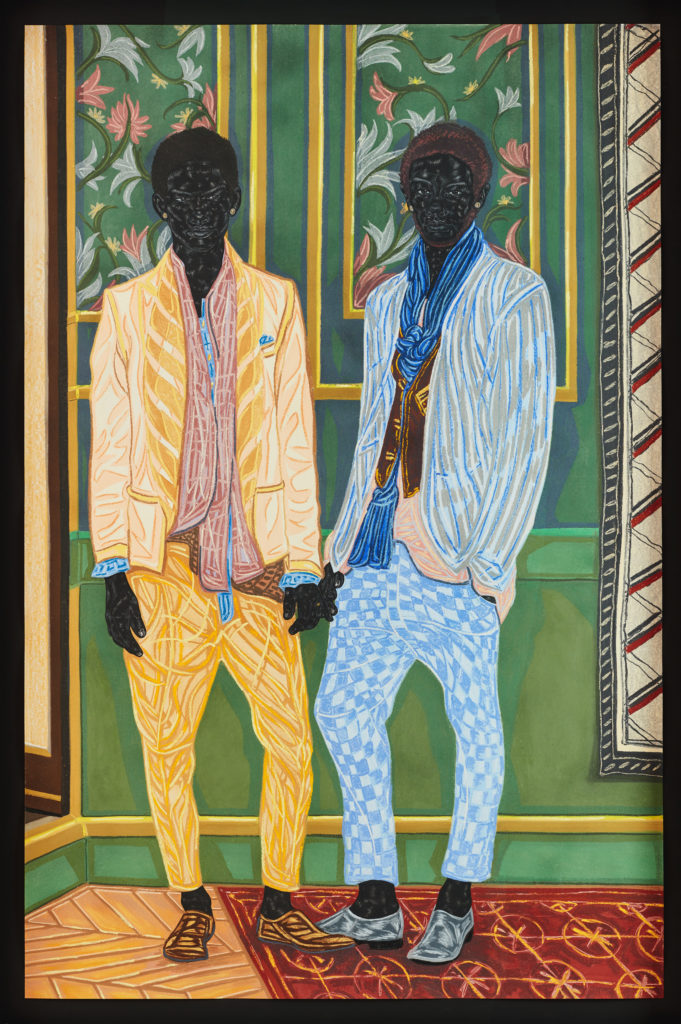

Toyin Ojih Odutola, Newlyweds on Holiday, 2016 © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Throughout, Ojih Odutola evokes gender and sexuality in a grandiose manner. The exhibition is based on the union of a queer couple. The most dazzling and romantic portrait in the show is Newlyweds on Holiday (2016), a life-size portrait of two Nigerian men, dressed in a chic Naples Yellow and Cerulean Blue suit, adorned with gold earrings. The figure on the right gazes back at the viewer while the other stares into the distance. Their love flourishes as they both pose in contrapposto; the highlights on their skin, black as charcoal, glistens and forms their presence in an emerald green room. As coy and timid the figure on the left is, his commitment to his partner is signified by a gold band on his ring finger, and the discrete gesture of their fingers intertwining. On another gallery wall is The Missionary (2017), a portrait of a lesbian, which Ojih Odutola mentions she had to put in the show. Dressed in a pink blazer and accessorized with gold earrings and necklace, she gazes back at the viewer with a zig-zagging green landscape in the background. As taboo as these two portraits may be in African countries that have criminalized homosexuality, they are testaments to the presence of queers in Africa and the African diaspora.

Toyin Ojih Odutola, The Missionary, 2017 © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Although the characters in the exhibition are of Nigerian heritage, there are no symbols that signify their African-ness. Ojih Odutola’s oeuvre signifies the multiplicity of African-ness and Blackness in their mutual beauty. In “The Souls of Black Folk,” W.E.B Du Bois states, “The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, -- this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self… he would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa… he would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world.” Ojih Odutola works exemplify that a union and love between two Nigerian men is the message.

The Firmament was on view June 8 - September 2, 2018 at the Hood Downtown.