With the exception of the occasional great painting, usually Northern European, it is generally thought that the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston missed the boat on acquiring 20th century art. Particularly when compared to its renowned depth in 19th century French painting including a staggering 35 or so works by Claude Monet and the masterpiece of Post Impressionism, Paul Gauguin’s greatest single work “Who are we? What are we? Where are we going?” (Which was actually acquired in the 1930s). What happened? How could there have been such a profound reversal of taste from the adventurous collecting of the late 19th century, through the 1920s, and the utter collapse into provincial conservativism that prevailed until former director, Perry T. Rathbone, a Brahmin director and good old boy straight out of Central Casting, finally relented, moments before being pushed out the door as a result of the Raphael scandal of the Centennial Year, and caved to pressure by creating the Department of 20th Century Art and appointing its first curator, Kenworth Moffett, in the absurd year of 1971.

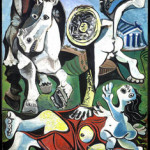

That was a pretty late date to start playing catchup on 20th century art. The MFA bought its first Picasso, a late pastiche “Rape of the Sabines” in the 1960s, Picasso being Picasso, when Perry and his buddy, Hanns Swarzenski, curator of decorative arts and sculpture, visited the artist’s studio and bought the painting still wet off the easel. Much later, the museum acquired “Standing Woman,” 1908, an excellent but frightfully expensive analytical cubist painting and another work of the period from 1911. However, just three representative, but not major, works by one of the most important 20th century artists is rather embarrassing for a museum of global status. All of those three works are sprinkled about in a sprawling overview of art of 20th century that combines two separate shows “Facets of Cubism” and “Degas to Picasso: Modern Masters” that meanders about in a gaggle of galleries.

It is director Malcolm Rogers attempt to get some street cred in the field of modern art. Many of the works by minor modern masters haven’t seen the light of day for decades, if ever. Seen as a whole, these tandem exhibitions attempt to overwhelm visitors in their sheer numbers and command of wall space. There are some 280 plus works on view in the Degas to Picasso show. But, truth be told, other than the occasional painting, some of which are just terrific and a lot more not, this is a show of mostly prints, drawings and photographs; an area in which the museum’s curators collected intelligently and aggressively. There are all the right Picasso prints and a slew of great Northern European works to complement the museum’s better luck and taste in that realm. Simply put, for what it’s worth, in the 19th and most of the 20th century, the taste of Bostonians was far more Germanic than French. The focus of New York’s Museum of Modern Art was firmly French while Boston, in its limited ventures into contemporary art, preferred the Germanic. Witness the important Busch Reisinger Museum at Harvard University with its great Beckmann’s and Heckels. Curiously, Rathbone had been a friend of Beckmann in St. Louis before taking a job in Boston. There was a major Beckmann retrospective and another for Kirchner under his watch. Also, the weak and struggling Institute of Contemporary Art, under an early director, Thomas Messer, (later director of the Guggenheim) showed German and Austrian art. The ICA mounted the first American museum survey of Egon Schiele which I remember visiting as a teenager. It was a riveting and memorable experience. There were plans to merge the ICA with the MFA as its department of contemporary art. Messer even advised on some acquisitions including works by Karel Appel and David Park, but the plan fell apart when Rathbone became director with his own ideas, half baked, about modern art.

If the MFA blew it with Picasso it did not fare much better with Matisse. During the 1930s, when the MFA had like zilch interest in the art of its time, particularly under the influence of its venerable curator of Indian and Far Eastern Art, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (1877-1947), there was a quaint attempt to hedge its bets by making a few cautious and conservative acquisitions through a “reserve” fund. Which means that the works were on probation from the permanent collection. The museum was free to dispose of them at a later time with impunity. One of those works was Matisse’s “Carmelina” from 1903. Compared to what the artist would create after this early academic studio nude it is rather tame. But, as Walter Muir Whitehill recounted in the official two volume history of the MFA, a trustee blew his top and resigned because he no longer felt safe taking his wife and daughters to the museum. The scandal and controversy reminds one of the French response to Manet’s “Olympia” but that occurred in the 1860s and Boston waited until the 1930s to freak out. The museum kept the picture, today one of its too few treasures of modernism, but did not rethink its position for another 40 years, despite Rathbone’s occasional dilettante efforts.

By then, arguably, there was too much water under the bridge ever to catch up with modern art. But even after the appointment of Moffett the pratfalls and farce continued. When he lured a great Pollock to the museum “Lavender Mist” the trustees turned it down as too expensive and technically risky. It was snatched up by the National Gallery just a short time later. That’s another one that got away. When the MFA did wise up on the importance of Pollock (after a couple of minor acquisitions by Moffett) it paid dearly for the seminal and transitional “Troubled Queen” notably swapping for it a Monet and two Renoirs plus cash. Basically it traded apples for oranges.

Under former curator of American Art, Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. the MFA got lucky in acquiring more than a hundred choice examples of early American modernism from William and Saundra Lane. Later, Saundra Lane gave many important photographs to the museum. With one move the MFA became respectable in filling a gaping hole in its legacy of arrogant neglect.

But, unfortunately, there are no other great Boston collections rich in 20th century masterpieces on track to find their way to the museum. The historic indifference of the museum to modern and contemporary art sent a chill through the community from which it is just now defrosting. In one sense what’s done cannot be undone. There will always be those embarrassing gaps in the collection which, in all other areas, views itself as encyclopedic. It is perhaps telling that one of the most famous Brahmin institutions is known as the Myopia Hunt Club; because the nearsighted riders were presumably falling off their polo ponies. But the amusing title might just as well describe the MFA’s mostly blind trustees; then, and perhaps, even now.

We are entering a great new phase of the arts in Boston. The MFA is in the midst of a dramatic expansion designed by Lord Norman Foster. The plans call for greatly expanded gallery space for modern and contemporary art. These sprawling shows presented under the familiar Rogers mantra of “One Museum” offer glimpses of what one will see. Behind the scenes the contemporary department is said to be moving aggressively. This fall the Institute of Contemporary Art will open a new 60,000 square foot venue on the Boston waterfront with some 18,000 sq.ft of exhibition space up from its current 6,000 sq.ft. Boston’s curators and museum strive to be players now and in the future. Given the institutions and individuals, however, just why do I remain skeptical? Perhaps it is just Boston being Boston. What happens in Boston stays in Boston. Forever.

Links:

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

"Facets of Cubism" is on view December 7 - April 16, 2006 at The MFA.

"Degas to Picasso; Modern Masters" is on view January 18 - July 23, 2006 at The MFA.

All images are courtesy of the MFA.