Danielle Abrams’ (b. Queens, New York; lives and works in Boston) performances describe the multifaceted components inherent to a personal and radical interpretation of identity. She utilizes humor and narrative in her work, asserting that “laughter, incited by personifications of family and influential figures, is the linchpin to a reinvigorated interpretation of the self and others.” Abrams’ ability to take on multiple roles translates into her daily life—artist, professor, curator, and researcher into the Boston arts community who continues to have an impactful, rippling effect across generations of artists. Abrams is the Professor of Practice in Performance as well as Graduate Faculty at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University. Her work has been exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Boston, and she received the 2018 Distinguished Artist Award in Performance from the St. Botolph Club Foundation.

She has facilitated exhibitions for her students throughout Boston and surrounding areas, including AREA, Thomas Young Gallery, Temporal and Corporeal Performance Festival at University of Ohio at Athens, and recently Performance Pop-Ups at the Museum of Fine Arts Late Night series in May 2018. On June 10, 2018, she curated performances at the Museum of Fine Arts Summer Party that Abrams said “responded to the indigenous collection of objects and ritual form.” She maintains a close connection to New York and has exhibited at The Kitchen, Panoply Performance Laboratory, and more. Abrams has additionally exhibited at the Queens Museum, Bronx Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of the Arts, and Labotanica at Project Row Houses (Houston).

Chelsea Coon: What is your approach to realizing performance works?

Danielle Abrams: I am drawn to duality. As an art student at Queens College, I was obsessed with Coney Island—in particular, the memories that came from my childhood spent during NYC’s bankrupt recreational facilities in the 1970’s. I perceived the sharp distinction between two realities at Coney Island, divided by the boardwalk. The escapist carnality of a wooden roller coaster and death-defying rides was antithetical to the world I witnessed below. In the dark cool sand, my father took me to pee. Amidst the patterns of slanted light, I witnessed junkies nodding out, Hells Angels in full leather and lovers in erotic embraces I knew were too X-rated for my seven-year-old eyes. Unlike the smells of cotton candy and sea air that dominated the amusement park, the world below smelled sour, urine-drenched and like the fabric of intoxicated bodies.

My persistent memory of two Coney Islands was a prototype for my performance of identities. The divided realities I witnessed were a map that showed me how to traverse my biracial and queer identity—black, Jewish and a butch dyke. Coney Island taught me how to embrace and re-presented the polarities of my own identities. In Quadroon (1998), I performed the idiosyncrasies of my white, Jewish and African-American grandmothers adjacent to a butch entrepreneur and a teenage self that longed to pass for Greek.

Currently, I am spending time in New Orleans researching a performance. I have always been drawn to New Orleans because of its lore and the mythology that surrounds mixed-race people of African descent. Last summer I spent time learning about the rich eccentricities of the city. Like Coney Island, New Orleans is riddled with dualities, whether pertaining to its own memoir, its expressive forms, its victories and catastrophes, and the passage of its people from life to death. I absorbed everything I could learn about the city including the struggle to remove the ubiquitous monuments to the Confederacy, Black Masking Indians, the evolution of the lower 9th Ward since Hurricane Katrina, sunflower sustainability, Creole cuisine, Southern “outsider” folk art, the sound of brass bands in the street and the current climate of the city according to local folks. In particular, being exposed to the histories of the Free Women of Color, the Quadroon Ballroom, and Plaçage, led me to develop Shades of Gras, a performance that is a psychogeographical tour through the city. In the performance, New Orleans is still flooded, Creole edibles are tossed as trinkets from parade floats and the embalmed awaken to speak. My train journey down South echoes the travels of Pinky, the light-skinned African-American main character from Elia Kazan’s 1949 film titled Pinky.

An excerpt from Shades of Gras (Performance Script, Danielle Abrams, 2018):

“Pinky and I were both lookin’ for somethin’. She in the North, me in the South. In the North, Pinky wanted to become a nurse. But she also wanted to see what it would feel like to be white. In the South, I too wanted to pass. Amidst the light skin Creoles that I had seen pictures of, I wanted to see if I could pass past white. Down there, folks might finally see me as black.”

Pinky opts to pass when she’s seated in the white section on the Southern Railroad to the North and does not inform the conductor. She also does not adjust the white doctor’s gaze, when he asks to marry her assuming she is white. In Shades of Gras, my racial identity also complies with the perceptions of those I encounter. New Orleanians refer to me as “white girl,” blanc d’pasange and say they can detect my blackness through my “little, chubby feet.” My racial quandary is reinterpreted, however, when I return to the 1860s to attend a Quadroon Ball. In the mythic manner of the day, I am looking to build a common-law relationship, but with Brad Pitt. Plaçage dictates that I will be his black wife, and he will set me up in one of his eponymous “Make-it-Right Houses” in the lower 9th ward.

Danielle Abrams, "Shades of Gras," video still from performance (2018), Courtesy of the artist.

CC: Is there a problem or question that motivates your recent works? Is there source material you find yourself returning to in your live works because you want/need to interrogate it from another angle? In terms of process to the realization of the performance, how do these steps manifest in the projects?

DA: Since I was in graduate school, I have been interrogating the same question. It pertains to self-portraiture. How can one portray themselves when self-perception and identity are in flux? Naturally, I am influenced by W.E.B. Du Bois’ theory of “double consciousness”—interpreting one’s identity as an amalgam of two perceptions, one belonging to the dominant gaze. My interiority is, in part, shaped by my legacy and what I have been taught to be true about myself. However, there is a more direct influence upon the malleability of identity; one that is perpetually redetermined by encounters with others. A person of color may not intrinsically think about the way others experience their race until they are subject to social and professional marginalization, or the effects of being profiled and criminalized. Such experiences, even in the form of microaggressions, are potent determinants upon the composition of a self-portrait.

My own inheritance bestowed me with an inaccurate self-image: one that was Jewish, white, middle class and a Northerner. Although I knew my father is black with Southern lineage, I had very few guideposts for internalizing my African-American identity. I had even less for comprehending the experience that was unique to Southern blacks who migrated to Northern cities. My skin color became the determinant of how I was shaped by my family, and privileged institutionally and in the public sphere. I never questioned the access my skin color granted me until I began to dig deeper.

I always say to my students, “Art keeps you honest.” I’d also add that art keeps you “intersectional.” As I evolved into a queer identity, I realized that the expression of that identity was reliant upon the totality of my identity. One of my first performance characters, “Butch in the Kitchen,” ran a meal plan service for broke and marginalized queers in the Mission District of San Francisco. Butch made a video commercial, in which she explained how her meal plan subsisted on food stamps fraudulently acquired from the Welfare Office. She was awarded these benefits because of her institutional experience in the mental health system. She was hospitalized because of her dual cultural recipes for cooking chicken: I like to fry it up or I like to put it in a soup. Butch in the Kitchen eschewed the conventional representation of masculine-gendered dykes portrayed as stoic daggers or AGs for a self-portrait that was more nuanced, vulnerable and layered with discourse about class and institutional oppression.

It was around this time that I became exposed to the ideas and writings of two artists and scholars who have been prominent to me in their influence. As a graduate student at UC Irvine, I met with Professor Daniel J. Martinez, who punctured my allegiance to stable representations of the self. He simply said, “Okay, you’ve been performing as a butch dyke. What about the other parts of you that are African-American? Jewish? A woman?” Daniel’s questions preceded my reading of José Esteban Muñoz’s theory of “disidentification.” Muñoz lauds the possibilities of expressing contradictions in personae-based performance—particularly when those contradictions are embodied by the same performer.

Martinez’s and Muñoz’s ideas helped me recognize the integrity and potential of embodying personae that are critical representations of the self: a Jewish matriarch, an African-American femme Southern grandmother, a cocky butch dyke, and a teenage “tragic mulatto” who assigns herself a Greek identity. In Quadroon, these personifications were presented as a four-channel video installation, asserting the conundrum, absurdity, and poignancy of a multiracial and intersectional identity.

Twenty years later, I am still building this portrait. However, I wonder if what I am really working on is less of a portrait and more of an equation. Phrases like quadroon, octoroon, and mulatto, used in the mid-nineteenth century, once signified the quotient of black to white blood in a mixed race person. Language controlled the ways African-American mixed race individuals experienced privileges and rights in society. As discriminatory as it was, the language was very precise. Racism has become much more opaque and is often disputed and blurred by dominant and white voices. In my performances, I am looking to build a language with which to define white supremacy as well as my own experience of being mixed race, black and Jewish within racial hierarchy. That language will articulate the black/white cipher that is particular to the United States—and for which my own biracial identity is a barometer.

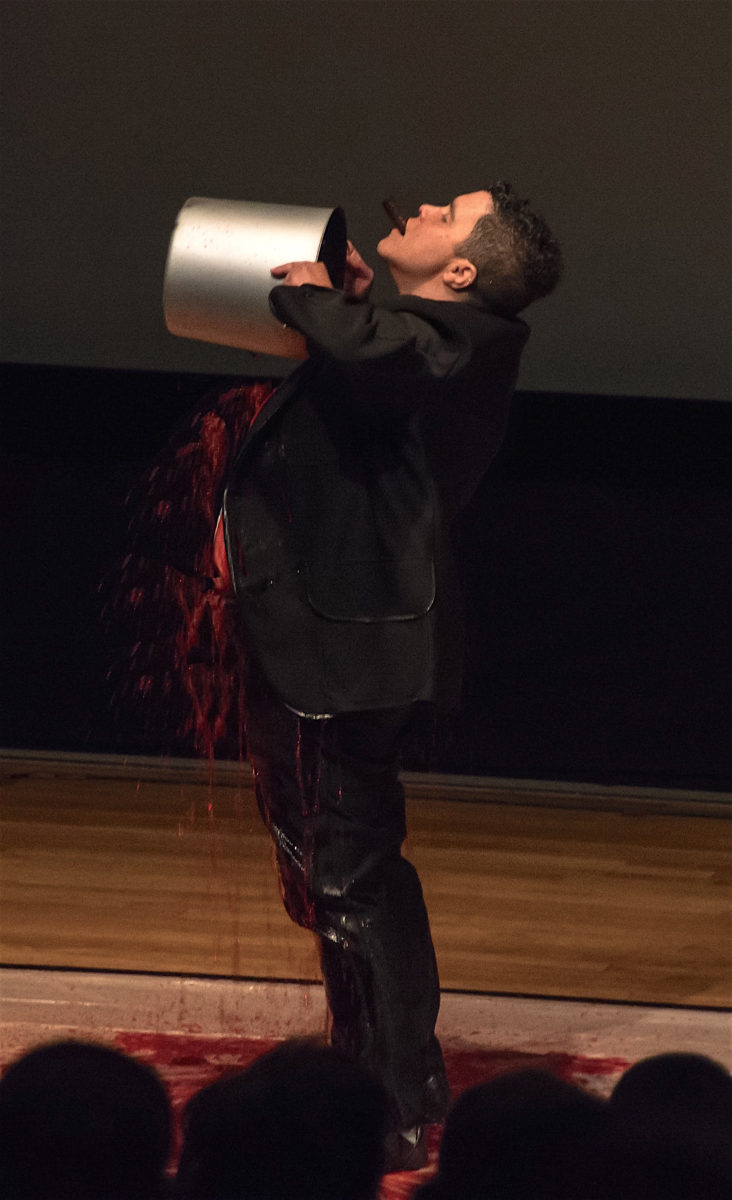

Danielle Abrams, "Routine," “DragFace” Tufts Graduate Colloquium, MFA Boston, 15 mins. (2016) Courtesy of the artist

My observations and inquiry about xenophobia and intersectionality are sometimes posed using abstract stand-ins: puppets of Barack Obama, Adrian Piper, and my Jewish grandparents. They are also communicated through slides that I animate with a range of ethnic voices. Sometimes, I appropriate distortions of black and Jewish identity. In Routine (2008), I performed as a comedian in a tuxedo reminiscent of Jewish humorists like Jackie Mason, Rodney Dangerfield and Henny Youngman of the Catskills, New York (a.k.a. the Borscht Belt). The predecessors of these humorists were turn of the century Jewish entertainers who wore blackface including as Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Sophie Tucker, George Burns and others. I asked myself if the image of a Jew in blackface was a bizarre parody of my own self-portrait? This question led me to appropriate a Catskills comedian persona, along with his barrage of conventionally sexist, homophobic and self-deprecating jokes. In between the jokes, I submerged myself in a 25-gallon bucket of borscht, turning my face beet red. The penetrating stain of the beet-based soup could be understood in many ways—as the embarrassment of this Jewish legacy or as a kind of bloodletting or cleansing—a mikvah. My intention was to review and resignify the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century blackface mask—one that paradoxically functioned as a Jewish portal to assimilation and whiteness.

Along similar lines, I was always fascinated and flummoxed by Eleanor Antin’s embodiment of the black and Russian ballerina, Eleanora Antinova. Was Antin also a Jewish artist doing a blackface performance? Or was her character a precedent of postmodern identity-based performance. I contacted Antin and told her I was going to restage her 1979 performance Before the Revolution. We had a playful email exchange but didn’t talk much about the performance. She is so astute, and in our casual exchange, she observed some interesting parallels between my sister and me. I took this as a sign that there might be potential in entering a parallel universe with Antinova herself.

In Before the Revolution, Antin’s fictitious ballerina Eleanora Antinova is counseled and criticized in a patriarchal manner by the founder of the Ballet Russes, Sergei Diaghilev. Diaghilev was a cultural revolutionary, yet discourages Antinova from being a Russian ballerina when he tells her that she will be “blackface in a snowbank.” In my 2009 retake of Antin’s performance, I appropriated the original script, wore a tutu, and mimed her signature life-size puppets on wheels. When Antin performed as a black ballerina in 1979, she wore obvious dark makeup (a sign for blackness) as a means of confronting racism in the New York art world. Almost forty years later, we now construct our tactical masks with different tools. Instead of appropriating blackness, I appropriated Antin’s performance. Blackness as a mask was redundant as I am black. By replacing Sergei Diaghilev with members of the Black Panther Party, my performance became a lesson, instead, in the choreography of black identity. Antin performed Before the Revolution at The Kitchen in New York City. My performance, After Before the Revolution (2009) was performed at the Detroit Institute of the Arts. With life-size puppets of Stokeley Carmichael and Huey Newton, we pivoted far away from the ballet stage to relive the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, and a Black Power Utopia sustained by the adornment of flaccid rifles and a 10-point plan.

Danielle Abrams, "After Before the Revolution," Detroit Institute of the Arts, 20 mins. (2009) photo by Kris Kurrawa, Courtesy of the artist.

CC: Could you speak to the idea of comedy as a vehicle to disseminate a message and the way that this functions in your performance compositions?

DA: My works begin dialogically—through conversations with others. When I sit down to write a script, I internalize what I’ve heard, what I’ve said. When I start writing, the text goes through my ethnic “hoppers.” Language and logic are inflected with Jewish irony and cynicism (a.k.a. Jewish jazz). I am equally informed by the wordsmithery of African-American folk speech. Rap, preaching, storytelling, signifyin’ and dissin’ influence the rhythm and logic of my monologues and plays. When I make someone laugh—on or offstage—I feel kinship. I also feel that we are sharing in one of the most profound forms of knowledge. Laughter emerges through the body. When we laugh, there is a call and response. The language of humor is downloaded and delivered all at once in the mind, spirit, and body.

CC: You’ve been teaching performance for several years now. What courses and themes do you offer? What do you think are the most challenging components of teaching live work?

DA: I have taught in performance, interdisciplinary and cross-media programs for close to twenty years. In addition to teaching courses in Beginning and Advanced Performance as well as advising MFA students, I teach seminar-style studios that augment SMFA at Tufts’ Performance Area. I’ve taught courses in “Social Engagement: Practice and Theory.” In that class, students will form partnerships with community activists and organizations in Boston. Students have worked with a range of partners including Hyde Square Task Force, NuLaw Lab, Haley House Soup Kitchen, Bikes Not Bombs, Partnership for Whole School Change, and others. While students are participating in organizational structures that engage communities, I try to bridge the gap for them by showing them practices that have straddled art and the needs of a community—work by Suzanne Lacy, Rick Lowe, Women on Waves, Simone Leigh, Theaster Gates, and others.

In many ways, this is a class that is always being revised. I’m not sure it is necessary to assume the need for a bridge between art and activism, volunteerism, or social engagements. The most potent art practices work deeply and often come from social reciprocity. The navigation of relationships and conversations with community members, building birdhouses or creating an archive of their organization can be more substantive in building an art practice than sitting in one’s studio. I also recall a former student from the University of Michigan, Charlie Michaels. On a panel at the “Open Engagement Conference” a few years back, he said there wasn’t a need for his art practice and community-based work to connect. It was a courageous admission. It turned a few heads and made others breathe a sigh of relief. Truth be told, Charlie later went on to collaborate with a Detroit street painter named Bird. Together, they invigorated an abandoned billboard in Detroit with a painting of a star-lit nighttime sky.

Performance, like life, presents the body with all of its codes and signifiers. The body is one of the best forms with which to provoke audiences’ assumptions about race. However, all art is a racial provocateur—especially art which deems itself “apolitical.” In the spring, I will be teaching a course called “Race and Performativity.” In this class, I am interested in working with my students to explore visual and optical culture. What is white art? How does it perform? What are the socio-political conditions that make something Asian, Latinx, “tribal,” or Afrofuturist art? Have these categorical distinctions been oppressive or emancipatory? With this inquiry and analysis, students will develop works that activate racialized and ethnic codes. Can a student’s work get “whiter”? What happens when codes get blurred or ethnic signifiers become appropriated? My ultimate goal, as always, is to produce a consciousness in my class that enables utterances of the unspeakable, transforming students’ methods and conceptual approaches. Their art practices should coincide with engaged and principled citizenship.

- Danielle Abrams, “Quadroon”, performance for a 4-channel video installation, 40 mins. (1998), Courtesy of the artist.

- Danielle Abrams, “Shades of Gras,” video still from performance (2018), Courtesy of the artist.

- Danielle Abrams, “Shades of Gras,” Temporal and Corporeal Performance Festival, Ohio University at Athens, 30 mins. (2018) photo by Naketa Forde, Courtesy of the artist.

- Danielle Abrams, “Shades of Gras,” St. Botolph Club, 30 mins. (2018) photo by Anthony Young

- Danielle Abrams, “Routine,” “DragFace” Tufts Graduate Colloquium, MFA Boston, 15 mins. (2016) Courtesy of the artist

- Danielle Abrams, “After Before the Revolution,” Detroit Institute of the Arts, 20 mins. (2009) photo by Kris Kurrawa, Courtesy of the artist.