Un/Settled is a show of works on paper at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design. Curator Jan Howard has selected works by contemporary RISD alumni from the museum’s collection. The general theme, with numerous variations, is geographic dislocation and the fleeting quality of visual memory.

Maria Serena Perrone

American, b. 1979

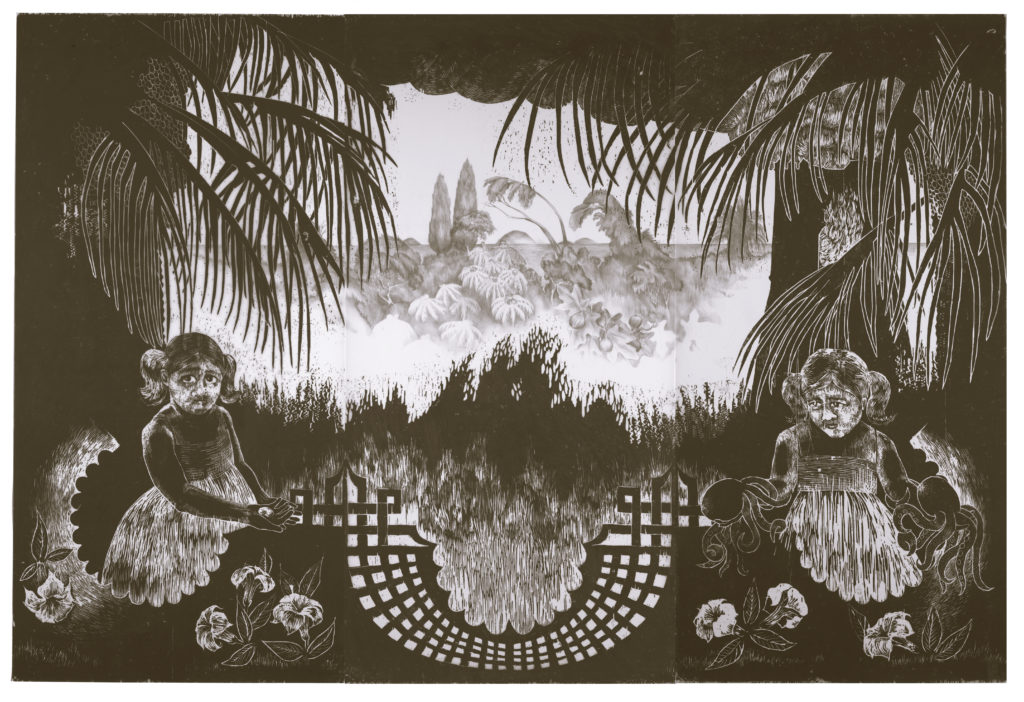

Tristessa: Reappearance of the Vanished Filicudi, In the Realm of Reveri, 2006

Three panel woodcut with silverpoint and goldpoint on frosted mylar

121.9 x 60.3 cm (48 x 23 13/16 inches) each panel

Gabor Peterdi Print Purchase Award 2006.93

Most arresting in the first room of the exhibition is Serena Perrone’s large woodcut printed in gilded bronze ink on mylar with added metalpoint drawing, titled Tristessa: Reappearance of the Vanished Filicudi (III) . Seen through the aperture of a kind of mystical heraldic matrix, a view of a landscape and the domed island of Filicudi in the Aeolian archipelago—a distant paradise lost and regained in the mind of the beholder—where palms, cypresses, and fig trees take shape through the mists of memory. This “reappearance” occurs in a large central vignette, which was left blank in each print of the edition, to be filled by drawings of the artist’s “constantly shifting” memories of her Sicilian childhood executed in silverpoint and goldpoint. Two bewildered little girls placed among palm fronds, flames, and hibiscus flowers flank the printed aperture that gives to the hallucination of Filicudi. The girl at the left offers a large octopus in each hand, whereas her counterpart at the right cradles a small stone or egg. These figures represent the artist as a child. The seemingly ubiquitous self-portraiture in contemporary women’s art can be tiresome, for me, at least. But these little girls are exceptional: they are large-scale memoirists, their eyes full of challenge and regret. They may personify “Tristessa,” a childish pronunciation of tristezza, or sadness, as experienced by the artist. Where are we here? In Sicily, the Greek, Arab, and Norman presences enrich a complex historical plot, but the allure of Sicily can be a location muffled in the modern imagination by heat, emigration, torpor, scarcity, and aching nostalgia. We are no longer in Italy here, but rather in a Mediterranean netherworld somewhere between Italy and Greece, a haunted, place, vanishing and reappearing in the artist’s imagination.

Brooklyn-based Glen Baldridge’s Bad Folks in Town is a large drawing made from acrylic and powdered graphite on paper. Horizontal lines of symmetrical filigree are arranged like stacked rhizomes in poetic form on a large vertical sheet, one horizontal fantasy following another. Because of the dense, granular quality of black in this medium, the drawing has the feeling of an etching and aquatint. This is no surprise, as Baldridge has a background in printmaking. The subterranean rootstocks in Bad Folks in Town are reminiscent of the nineteenth-century wood engravings that illustrated Bunyard Nursery catalogues and other eighteenth and nineteenth-century botanical books. A pear-tree espalier, for example, illustrated in a Bunyard catalogue, is a close cousin to Baldridge’s forms here. In the past, Baldridge has also made drawings with watercolor, powdered graphite, and silkscreen (Hideaway, 2013) that take on the demeanor of photographs and photographic negatives. He has also explored the quality of patterned overallness on flat planes that mimic minimalist paintings (Daylighter #2, 2015). From what we see in Un/settled, Baldridge has more than techniques and materials on his mind. Were he to give more consideration to engravings of botanical specimens his drawings might look more like prints, but as we see in Bad Folks, this can be a most captivating way of making drawings.

Tia Blassingame started out with an interest in architecture, but her artist’s book Settled: African American Sediment or Constant Middle Passage of 2015 is intimate and almost deliberately anti-architectonic in its usage and scope. This book of Blassingame’s original poetry is about African slaves who died during passage from West Africa to the West Indies on slave ships owned by the Brown family of Providence. During the 1764–65 voyage of the Sally, a Brown family ship, for instance, 109 of 196 captive people succumbed to suicide, disease, starvation, and outright murder by the enslavers. Contemporary figures such as Eric Garner (“I can’t breathe!”) also find place in this same poetic ode to African heritage and its tragic diaspora in the Americas. It might be said that the present installation of Settled is not optimum: it is rather difficult to see (let alone read) this book in its vitrine, but all its pages can be viewed online.

Justin Kimball, Oak Street from the Elegy series

The photographer Justin Kimball has a gallery of his own in “Un/settled,” called Elegy, referring to the body of work reproduced in his book (Elegy Radius Books: Santa Fe, 2016.) Is the United States in a state of moral, economic, and physical decay? If so, the history of American photography has a long tradition of documenting that squalor, from Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange through the twenty-first century to date, and to the work of RISD photography professor, Brian Ulrich, with his darkened stores and dead malls. Indeed, the photography department at Rhode Island School of Design, where Justin Kimbell studied, has had a vibrant reputation since the days of Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan. At RISD Kimball was a pupil of Joe Deal (1947-2010), who documented the human impact on the topography of American landscape. Kimball, instead, turns his eye to American small cities and towns. The bird’s eye view of the onset of poverty in one corner of the world has a decided Joe Deal influence. The majority of roughly contemporary pictures that document the impoverishment of our moldering cities and towns thrive on familiar derivative clichés of urban squalor. But Justin Kimball escapes the destiny of déjà-vu by being a colorist (and formal composer) of the most sensitive order. In the backyard scene of Oak Street, for example, Kimball introduces the pea-green water of an urban above-ground swimming pool which is morphing via neglect into a natural pond. Against this green is the aqua-colored plastic of the pool-cover partly submerged in the water, and the pastel green paint on one wall of an extension of the house. A view to the street, although foreclosed by the side of a house, suggests a fairly dense, if unseen, population. As is par for the course in such photography, Kimball does not miss the opportunity to find two bright and shiny U.S. flags and apply them parallel to the picture plane.

Justin Kimball, North Greenbush Road from the Elegy series

North Greenbush Road is a landscape, with fewer objects involved. Here again, Kimball speaks the language of Brian Ulrich’s portraits of blighted houses and sites. An abandoned house in a rural setting is collapsed, crushed like paper under the weight of its own powerful roof. We are prompted to ask: was this house ever inhabited? It seems not to be haunted, but rather in a state of physical decay. Some unidentifiable rubbish visually intuited through the missing panel of a garage door, suggests that someone once lived, or at least wanted to live here. In much the same way that ancient statuary reverts back to Marguerite Yourcenar’s proverbial “mineral mass” of stoniness when abandoned to nature, the lichen-covered basement of this house is returning, through neglect and forgetting, to its natural state, and sinking back into the earth.

Curator Jan Howard has an unfailing intuition for contemporary works of art on paper. Hallucinations, dislocations, abandonment, history, forgetting, and persistent but faulty memories, linger in the mind's eye of the beholder long after she leaves these galleries.

Un/Settled is on view at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art through July 8.