Blueprint for Counter Education, an exhibition on view at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis through July 8, turns each museum visitor into a “reader-looker-responder.” The term is one used by Maurice Stein and Larry Miller, the 1969 creators of the educational cosmos and “classroom in a box” that was Blueprint for Counter Education. The original edition was printed by Doubleday and went on sale in bookstores in 1970. This object was a genuine effort to map out—and radically redefine—the idea of a classroom environment as an aporia between lineages of great thinkers/authors/artists (mostly from 1890-1968) and the strange new social spaces of the late 1960s: riots, political meetings, happenings.

Blueprint for Counter Education. Image courtesy of Inventory Press

Maurice Stein was a Brandeis Sociology Professor and Department Chair, and Larry Miller was his student. Stein had been well-established within the field of sociology years before Blueprint. His 1960 book Identity and Anxiety, coedited with Arthur J. Vidich and David Manning White, provided an influential diagnosis for the age: the trance of consent which is the implicit objective and working mechanism of control in a society of advanced capitalism and mass media. Blueprint, then, was the result of a decade of passion and reflection; his attempt at a map for escape from the anxiety/control dilemma. The exhibition at the Rose adroitly conjures the methodology, milieu, and spirit of this pedagogical (and political) approach.

Blueprint for Counter Education, Installation view, Rose Art Museum. Charles Mayer Photography.

The main space of the exhibition presents reader-looker-responders with an array of handwritten classroom exercises and lesson plans, scrawled on large papers with interconnecting arrows and bubbles—“WRITE ON YOUR WALLS (Right on your walls)”—instructions along with diagrams, protest posters, and a limited selection of pieces by some of the artists referenced or implicated by Stein and Miller: Anni Albers, Jasper Johns, Eduardo Paolozzi, Yves Tanguy, Bridget Riley, and a few others. As I use each of these descriptors, “classroom,” “exercises,” “lesson plan,” they seem to belong individually in quotation marks to defamiliarize them, as Stein and Miller certainly were trying to do. Similarly, the works of art by familiar artists fit oddly in this grouping.

Blueprint for Counter Education, Installation view, Rose Art Museum. Charles Mayer Photography.

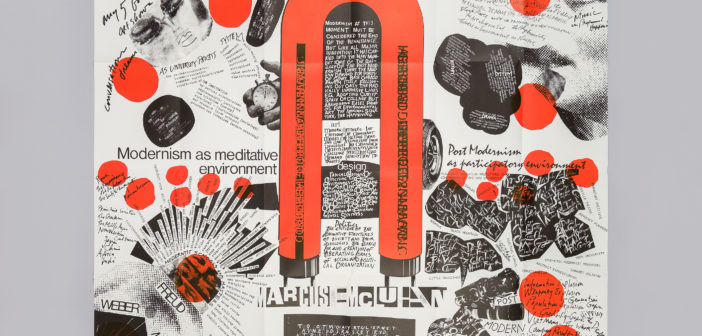

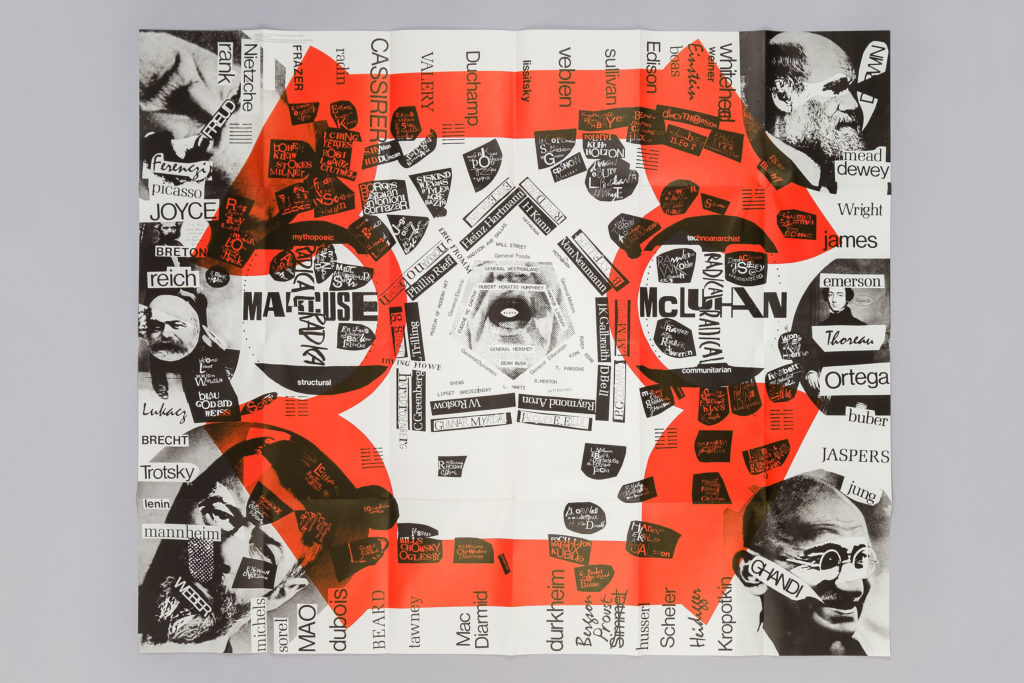

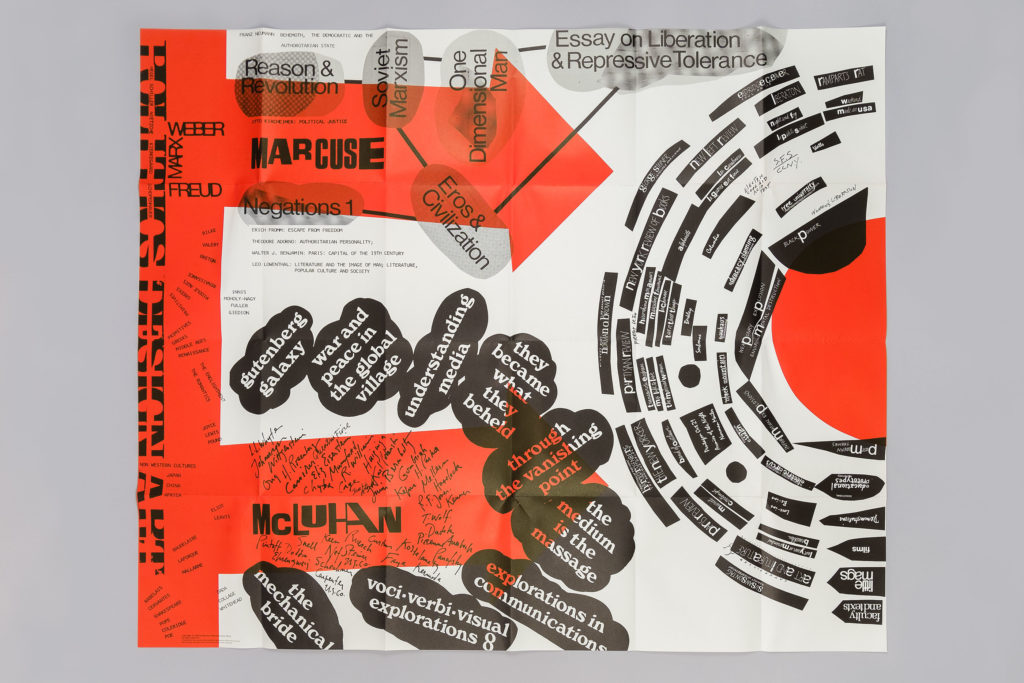

The Rose’s Mildred S. Lee gallery is a fairly small space accessed by descending steps from the already-below-ground main gallery space of the Rose. This size and situation are appropriate to the content of the exhibition since Stein and Miller’s work emphasized the spatial dimension of pedagogy and the importance of learning in unlikely places. The three poster-size conceptual charts, the centerfolds of the original publication, are displayed in the gallery and peppered with groupings of names. They encourage the participant to “drop all conceptions about cartesian space” or structuralist completeness, instead “[allow]one’s visual attention to wander” suggesting “three-dimensional chess or some other very complicated board game.” 1

Blueprint for Counter Education, Installation view, Rose Art Museum. Charles Mayer Photography.

An art gallery is an unlikely space for expansion of this classroom in a box, meant to be experienced interactively and fluidly. The format of an exhibition in a museum would seem to defeat their intention for a Malrauxian “museum without walls” by reinscribing this street-ready kit into a museum space. The “Instructions for the Confused Undergraduate” and a few other handwritten lesson plans on display suggest that students “1. Go take a walk.”; ask them “What is your immediate environment?”; “WALK through the library[…] physically, meditatively”; “5. Take another walk.” The posters, so they suggest, should be tacked to your wall or tied onto your bed. All this suggests a desire for covalence with habits and spaces of everyday life, including private life. To Stein and Miller, these are structured and saturated by affects of modernist conceptual regimes: Freud, Marx, Weber, and what we would call the deep state. Acknowledging this condition through embodied reflection was supposed to be the first step toward entering their revolutionary idea of “Postmodernism as Participatory Environment.” Commentators are quick to point out this kind of shortcoming, praising the authors’ radicality yet condemning their utopianism and optimism for revolution. Was the Blueprint for Counter Education a failure? Or have we failed it? In the “Elementary Instructions,” the authors describe the possible alternative think-spaces of their atlas: “If the theme appears too immediately menacing, or too involving, as one could easily suppose black power might to a black person in a ghetto on the day or a riot, a shift upward in the direction of a plausible faculty might help mitigate or clarify the menace in the situation described.” The game of three-dimensional chess has high stakes.

Blueprint for Counter Education. Image courtesy of Inventory Press

The video projection loop in the side space of the gallery shows archival footage from the opening events of the 1970 Rose Art Museum exhibition Vision and Television. We see a discussion with artists David Cort, Frank Gillette, Virginia Gunter, Nam June Paik, Stan VanDerBeek, and the exhibition’s curator Russell Conner, but it’s unlike any exhibition panel discussion you might see today. From the self-questioning yet urgent tone of the discussants to their crowded and disparate arrangement—some standing, some in chairs, interspersed with audience members—a contemporary observer is transported into one of the radical learning spaces that Stein and Miller wanted to enable. Viewed through grainy videotape, the camera wandering from face to face, this document evokes the famous opening scene of Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point, a meeting of radicals at a university in Los Angeles, filmed in exactly the same way:

[Plaintive white male student:] What if you want to end Sociology?

[Black male student:] Molotov cocktails are a mixture of gasoline and kerosene. White radicalism is a mixture of bullshit and jive!

[White woman student:] You know, I don’t have to prove my revolutionary credentials to you, you know there’s a lot of white students who are already on the streets fighting, just like you guys do in the ghetto. And, you know there’s a lot of unhappy dissatisfied white people who are potential revolutionaries.

[Second black male student:] Y’all dealing with things that are really irrelevant, you’re going back to the same thing, y’know, you get busted for grass and that makes you revolutionary. No, when the pig’s busting you on your head, kicking down your door, stopping you from living when you can’t get a job you can’t go to school you can’t eat, that’s what makes you a revolutionary, you dig?

The protagonist of Zabriskie Point turns his back and walks out of the room—“I guess meetings just aren’t his trip,” another student says with a shrug—and the film goes on from there. I mention this scene because it shows an alternative product of the cult of the “participatory environment”: boredom and flatness against urgency and thrill. Stein and Miller’s diagrams do not explicitly address these symptoms of disconnection, but the two mainstay figures of their schema, Herbert Marcuse and Marshall McLuhan, both do in their own work. McLuhan’s formulation of “hot” media as spoon-feeding content to spectators and Marcuse’s diagnosis of society structured on alienated labor and sexual repression both warn of the psychological moods of a controlled subject. I sense that Caitlin Julia Rubin, curator of this exhibition, stands with Stein and Miller in awareness and care of this danger; the “participatory environment” is not for everyone and it is not panacea for anyone. It turns out that this modest art gallery format works wonderfully for Blueprint for Counter Education; the “Take another walk” spirit is fully present, as is the tentative attitude of Stein and Miller’s pedagogy. It is certainly optimistic, but not oversure.

- Quotations from the publication’s “Elementary Instructions,” unpaginated