This year’s MFA Thesis Exhibition at MassArt, which closes on May 12, packs both floors of Bakalar & Paine Gallery with selected works from eighteen artists. The show is overwhelming in the sheer quantity of pieces on display as well as its overall strength—each of the MFA candidates merits praise for a cohesive and captivating body of work. However, in my viewing daze I was compelled to linger a little bit longer at three of the student’s contributions. I’d like to highlight these standouts in the profiles below:

Devvrat Mishra

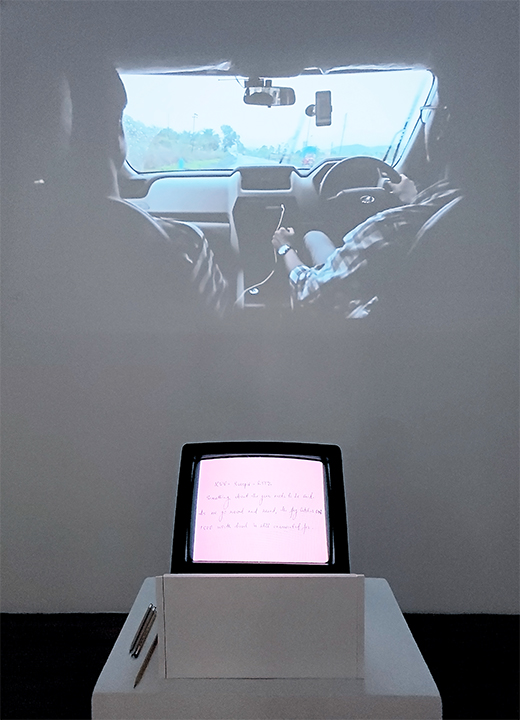

A tiny Toshiba television glows like a beacon on a pedestal in a darkened room. It stands before a large film projection playing candid vignettes of young Indian men. On the Toshiba screen, handwritten titles like “Zoom Car” and “Game of Balloons” announce new chapters in the film—six in total during the full eight minutes—then give way to short, existential missives in diary scrawl that correspond to the action in the film. The same handwriting, at times barely legible, is penciled in a few places on the gallery walls like clues. The lack of context feels intimate, like reading a stranger’s journal.

untitledINDIA ’17 is a multi-media installation by Indian-born artist, Devvrat Mishra, documenting his recent travels around India. The film component feels perambulatory, like we’re tagging along on an adventure. At one moment, we are in a car going fast. At another, a young man in a black and white striped shirt stands smoking a cigarette, framed by a green field and overcast sky. At another, two men prepare poori naan at dusk among celebratory pink and blue balloons. Oil sizzles and crackles. At another, drapery billows inside a bedroom window.

It takes a minute to realize that Mishra’s use of sound in the film is suggestive rather than matching what’s happening on screen. It does not immediately come to mind that a finger brushing across a photograph of an ocean would not make the sound of waves crashing or that throwing rocks at a beer can would not incite a crescendo of bursting balloons. But somehow, through convincing visual cues, Mishra suspends belief, and it makes sense. The sounds become textural layers. A self-described visual storyteller (and I would argue auditory, as well), Mishra ventures into the space between reality and fiction, painting a lush portrait of the everyday.

Molly Dressel

Molly Dressel’s sculptures have a presence about them, a gravity that connects them intimately to the earth. They are big, bold, and so elegantly designed that one might be tempted to call them simple. Quiet and physical, Dressel’s work captures the dynamic forces of tension and release, pushing and pulling, which are always in flux. In Sprung, ribbons of wood stream upwards from a small steel pipe into arches of varying amplitudes. The object is stationary but has all the line and motion of water spraying from a fountain. The ends of the ribbons rain into a wide circle of steel, seemingly disappearing into the ground only to cycle upwards again through the original opening.

Molly Dressel’s sculptures have a presence about them, a gravity that connects them intimately to the earth. They are big, bold, and so elegantly designed that one might be tempted to call them simple. Quiet and physical, Dressel’s work captures the dynamic forces of tension and release, pushing and pulling, which are always in flux. In Sprung, ribbons of wood stream upwards from a small steel pipe into arches of varying amplitudes. The object is stationary but has all the line and motion of water spraying from a fountain. The ends of the ribbons rain into a wide circle of steel, seemingly disappearing into the ground only to cycle upwards again through the original opening.

In Falling, two head-high beams of steel diverge making a “V” shape, leaning in opposite directions as if they are falling to the ground. A thin strip of bronze belts the form on a diagonal, appearing to stretch under the weight of the beams like a rubber band on the verge of snapping. How Dressel manages to make bronze feel flexible—stretchable—is no small feat. The tension built is gorgeous and unbearable.

The overall strength of Dressel’s work lies in the way it taps into lived experience. Wood, steel, and bronze are transformed into understandable gestures, gestures that are fundamental to our physical experience in the world. We know how water arcs and falls as it spurts from a pipe. We know the way it feels to try and hold something together as it begins to collapse.

Barbara Ishikura

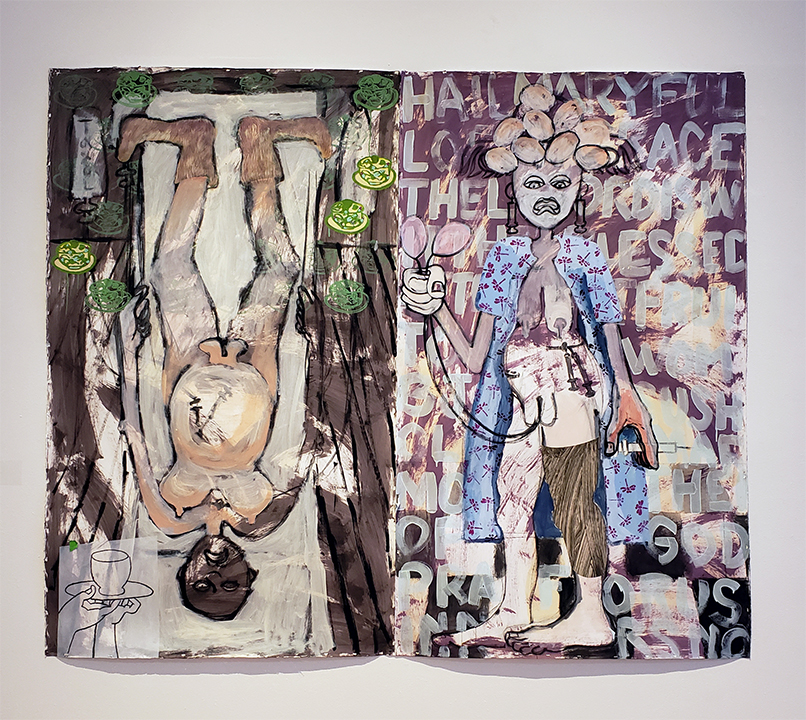

The scrappy exuberance and unabashed humor in Barbara Ishikura’s works on paper prove that refinement and unruliness don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Her style—a whirlwind of brushy marks, drawing lines, drips, and vibrant colors—lends itself to the multilayered narrative of her main subject: an “autobiographical female character who has confronted illness” and who must confront mortality, faith, and the existence of her body.

The scrappy exuberance and unabashed humor in Barbara Ishikura’s works on paper prove that refinement and unruliness don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Her style—a whirlwind of brushy marks, drawing lines, drips, and vibrant colors—lends itself to the multilayered narrative of her main subject: an “autobiographical female character who has confronted illness” and who must confront mortality, faith, and the existence of her body.

The female body and genitalia appear as a motif throughout Ishikura’s five paintings, often rendered in jarringly cartoonish detail as over-enlarged labia or external organs outside of the body. In Hail Mary, the character is pictured in an open hospital gown clutching her ovaries in one hand as if they were tiny balloons. She stares at them—appalled or in disgust—holding a syringe in the other hand as another pokes out of her side. Two more dangle from her earlobes as earrings. Behind her, the words to the Hail Mary prayer loom in ghostly blue lettering.

Ishikura’s proclivity for satirizing faith, namely Catholicism, does not read at resentful. Rather, as with her diverse and active mark making, it feels like a coping mechanism. Like her hospitalized subject, Ishikura’s process for dealing with sickness and facing death is splayed out on the examination table. What do we do when our bodies don’t work the way they are supposed to? What good is having faith in dark times? Ishikura’s work is an ode to the crisis of being alive.