Imagine, if you will, the following scenario. Intrigued by a book of poems you’ve just discovered at your local bookstore, you decide to get in touch with its young author with an appreciative mail. (You’re about the same age, and you notice in her bio that you share an alma mater, so why not?) Finding her contact information online, you send a short note expressing your admiration for her work and asking, if she has a minute, might she say what inspires it.

Here’s what comes back:

“My praxis resides at the interstices of race, class, and gender. Utilizing the myriad stratagems of late-Capitalist critique, I seek to triangulate the hegemonic constructs that underlie white heteronormative culture while simultaneously disrupting the performativity that perpetuates it. By interrogating the…”

It goes on—for six paragraphs. But you don’t make it to the end; by the time you reach the Deleuze quote you’ve lost all interest in the poet – and perhaps even in the work. Perhaps you’ve also lost interest in the bookstore that sells it.

And perhaps now you’re protesting: surely this would never happen. And of course, it wouldn’t. But the reason it would never happen is not that no artist would describe her own work in such absurdly turgid prose. The reason it would never happen is that the only artists who would are visual artists.

John Keefer, "Command/Control Alt," 2018. Oil on canvas, 80"x 60." Courtesy of Fred Giampietro Gallery.

I am a visual artist. I am also, be it noted, somebody unequivocally supportive of social justice. But as someone passionately committed to the native power of our medium, I’ve grown increasingly pained by the language in which so much of it is packaged. Nary a press release or artist’s statement these days is innocent of “interrogation” (“X’s work interrogates the theatricality of x, y, and z”), and “disrupting reality” has become an aesthetic imperative (“by problematizing the corporeality of [insert big word here], X’s work disrupts reality, complicating notions of [and another one here]”). Going by the language alone, an outsider to our field might conclude that visual art is enjoying a moment of great cultural authority. But who among us believes this? What I suspect we all know, and what I see becoming all the more obvious, is that beneath the exorbitant claims and overwrought verbiage there’s a deep-seated despair, a real crisis of faith.

In what, exactly, have we lost faith? The answer is to be found in the language itself.

“Interrogate” is a word redolent of power. Law enforcement, the military, the CIA interrogate; muscular and serious, “interrogation” means business. What about art? Does art interrogate? I can tell you that I’ve met plenty of serious paintings in my lifetime, and none of them ever has. Many have explored, questioned, or challenged, but grilling under threat of violence I have not seen (nor, it must be added, would I particularly want to). Of course, it’s the metamessage that matters here; the word is used to invoke authority. But the tone is so strained that the claim loses credibility in direct proportion to its bombast. Similarly with “disrupting reality,” which warns of grave consequences. Wars disrupt reality, as do strong earthquakes. A small meteor, depending on where it landed, might do this too. But aside from a Richard Serra sculpture or two, I know of no artworks that have disrupted reality—anyone’s in particular or the one we all share. And then there are the ubiquitous substitutions—“problematics” for “problems,” “utilize” for “use,” “praxis” for “practice”—that are meant to signal intellectual sophistication but that in fact do the opposite. Anyone who has a praxis may be many things we don’t know, but one thing we do is that she’s intellectually insecure. And no amount of Latinate words is going to make bad work better. Nobody’s fooling anyone.

If the words betray a loss of faith in our cultural authority, our sense of agency, and our worthiness of respect, they also, and again inadvertently, reveal the source of the anxiety. For visual art is above all a silent medium. Only be penetrating the scrim of language does visual art do what it does—namely, grant us access to the deeper regions of the psyche and the cognitive unconscious, that vast reservoir of knowledge we carry in our bodies. It is a non-discursive language for non-discursive thought. That we feel compelled to wrap our work in so much overblown prose reflects a deep insecurity about the value of the non-verbal. But isn’t its unique access to these tacit sources the reason visual art exists in the first place? An apology of sorts to the reign of the discursive, our verbiage is denuding our work of its very reason for being. In a culture that has the interior life under threat of extinction—and one in desperate need of alternative ways of thinking—this amounts to nothing short of a capitulation to what is.

It will be argued, of course, that artists are the victims here, that we’re at the mercy of market dictates none of us would have ever asked for, or that the lexical posturing of postmodernism has become what’s expected. But this is again a denial of our own agency. While it’s true that we aren’t the ones writing the press releases, we are the ones writing our statements.[1] We’re also the ones allowing the releases. If asking for a say in how our work is promoted sounds untenable, we do well to remember that the verbiage is founded on an insult—namely, that without the elaborate packaging our work is worth little.

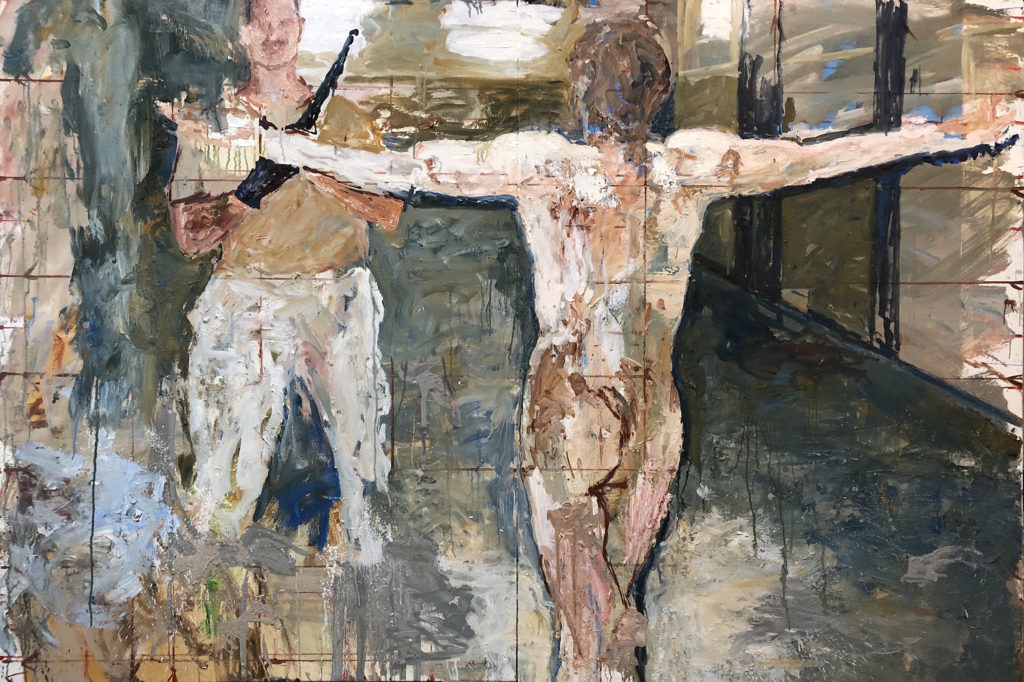

John Keefer, "Good Friday," 2018. Oil on canvas, 80" x 54." Courtesy of Fred Giampietro Gallery.

What is to be done? We can begin by asking ourselves what our work really means to us, and then writing naturally, without grand claims, something of what that is. No one’s saying this is easy. Writing about one’s own work is always particularly loathsome. (And how could it be otherwise, when, it bears repeating, art’s discursive silence is exactly its point?) But this is no excuse for letting others define what we do. If we consider the job not so much one of exposition as one of suggestion, of offering just enough information to draw others further into the work, the task becomes less odious—and can even be revelatory. No words for art, even those written by the most eloquent critic, will ever be anything more than pointers anyway, humble gestures toward meaning woefully aware of their own inadequacy. Artists explicitly engaged in social issues will object to the call for subtlety. But it’s they, especially, who would benefit from a lighter touch. For in truth it’s the not the issues themselves that are their work’s content but rather the way they’re embodied in visual form. And if the content of the work can be packed into a dissertation, may I suggest, politely, that the artist just do that. If the art itself is superfluous, please spare us its presence.

Greater authority, agency, and respect: if these are what visual art really wants, it might revisit its proud history as a countercultural force. Then it might ask itself a difficult question: with its bloated claims to self-importance and its disruptions and interrogations[2], in what way is it other to the culture we already have? A respect for nuance, subtlety, complexity of meaning; a tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity and the humility they give rise to; and above all a faith in our capacity to be better instruments of human intelligence: today, embracing these values seems the more radical stance. And as it happens, these are the very values our medium excels at transmitting. We needn’t do much. We’re already doing it. If our work speaks for itself, let’s stop interrupting it. And whatever we do—and here I implore you—let’s put down the big guns and stop the interrogation.

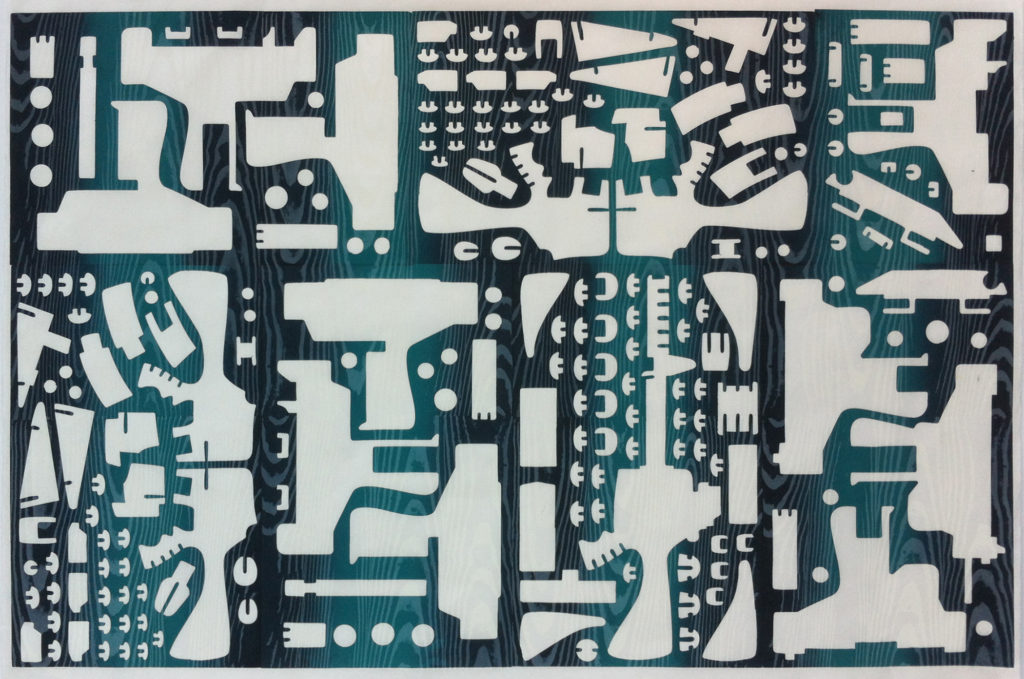

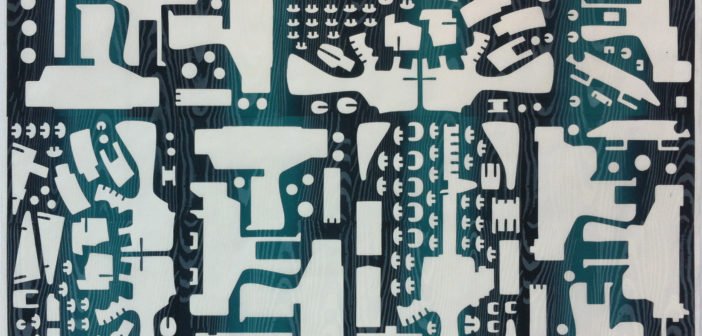

Jeff Woodbury, "Guns Like Water," 2015. 6-screen, 14-pull unique print on Mulberry paper, 25" x 37."

[1] Unless we’re not. Another distressing phenomenon is the rise of “promotional writers” for hire. Any artist who can think can write her own statement.

[2] To say nothing of its capitulation to rank commercialism. But that’s a subject for another essay.

8 Comments

Lexical posturing, indeed. I’ll take more discursive silence any day. You’ve really hit the nail on the head, and I THANK YOU for it!

Thank you for this very important essay! I’ve seen painters shift away from complexity and nuance towards a simplified visual text under institutional pressure (within undergrad and grad programs.) It saddens me. Paintings aren’t antagonistic to the aims for social justice, just as you say. But many programs are making painters feel irrelevant unless they use overblown didactics and keep the visuals secondary to the text. Thank you for reminding us of the radicality of “a respect for nuance, subtlety, complexity of meaning; a tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity and the humility they give rise to…”

Your title in itself made it all. Thanks…

I will appreciate you had a look at : http://www.clarissenoll.fr

enjoy your day

Thank you! I loved this! As a curator working at an institution with a broad range of visitorship, I see it as my mission to present work in a way that makes it accessible, no matter your knowledge of Deleuze and post-modernism. Conceptual work is often really challenging for the average visitor to enter and engage with. I don’t need to make it even more so by using fancy “isms” and name-dropping obtuse philosophers. The best writings communicate clearly and succinctly. When I come upon writing like that, it bores me to death and my first thought is “someone is just trying to sound smart.”

Very good. Thanks. Thanks also to the various online artist statement generators for the laughs they provide.

ugh yes. academic hot air writing so needs to stop

Speaking up for the visual, the subtle, the personal as we must.

A good statement requires thought, and sometimes digging deep into one’s own motivations for making it, but that doesn’t mean borrowing fancy stock phrases. I actually like to write about my work because a statement sets up lines of communication and commonality that enrich the viewer’s experience. Thank you for saying so well what I often feel as I wince at yet another wall text.