Contemporary Master Drawings at Cade Tompkins Projects continues Tompkins’s mission of exhibiting compelling contemporary art. All of the drawings on view in Providence until April 28th were also presented in New York in Master Drawings New York 2018. Since its founding in September 2009, Cade Tompkins Projects has become the locus of sophisticated exhibitions like this one, where viewers can wander from the transcendence of Nancy Friese’s monumental watercolors, to the frozen, foreboding industrial landscapes of Allison Bianco, to the tersely cerebral edges of Max van Pelt’s drawings (about modernist abstract paintings), to Dan Talbot’s careening street scenes, and finally to Serena Perrone’s stunning peep-show (in a porcelain box) of a mythopoetic Italianate alterity (Fata Morgana).

Sophiya Khwaja, Skating the House Out for a Walk

Pakistani artist Sophiya Khwaja’s two wistful, figurative drawings depict the artist herself out for walks in a deluge of rain (think Leonardo, for these pictures are as compulsively dense with humidity as Leonardo’s late landscapes). Hard rain is described in persistently aggressive graphite marks (and incisions) on paper, another conceit that chimes with Leonardo’s drawings, whether intentionally or not. Skating the House out for a Walk may be about the perils of domesticity, or the perils of leaving the home, as the artist herself skates at the high horizon in delicately rendered rain-boots, which are attached to the blades of kitchen knives. The small compact house is wrapped in a red thread, like the one that led Theseus out of the labyrinth (here it’s made of real thread that is almost indistinguishable from the artist’s handwriting of precise linearity). One ironic feature is a rain cloud that seems to follow the figure of the artist as she drags the house along by a thread. Both of Sophiya Khwaja’s drawings communicate a discreet sense of the absurdity of everyday life.

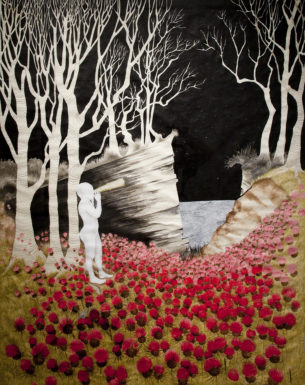

Serena Perrone, Mare Mosso

Serena Perrone resides in New York and in Tusa, Sicily. Her Mare Mosso is a mysterious nocturne, whose surrogate viewer is a nude little girl with a hint of a tail, gazing through a telescope through a chasm in the earth that gives view to a starry sky above and raging waves (the agitated sea that gives this work its title). Perrone dreams about Sicily and the Aeolian islands here, a poignant place that looms large in her childhood memories—where the earth is carpeted with cactus flowers, rosy thistles, and hibiscus blossoms—and in her everyday life at Tusa, where she also directs an annual printmaking workshop. Perrone’s work is very much about the cultural geography of the Mediterranean, both ancient and contemporary, where the Norman, Arab, and Byzantine civilizations are always both near and far, and the natural beauty of sea calls the beholder to an urgent longing.

Julie Gearan, Untitled (Study for Sea Legs)

Among the most captivating drawings in this show are those by Providence painter Julie Gearan, where traditional, masterful mark-making leads to a haunting and fantastic content. In Gearan’s Untitled (Study for Sea Legs), a nude human figure (apparently female) is seen crawling into the mouth of a whale in a powerful and exquisite meditation on the vast, unruly wilderness of the sea. The title of its companion drawing In Bocca alla Balena refers to two Italian idioms: “in bocca al lupo” (in the wolf’s mouth) and “in culo alla balena” (in the whale’s ass). Both of these phrases augur good luck to a person in a challenging situation. But, in my view, this clever, punning title gilds the lily of some seductive and extremely fascinating drawing: let’s leave this one without a title. Gearan’s interest in whales (which also has a strong presence in her paintings) is at once lyrical and somewhat frightening; her continuous lines and pentimenti move the viewer like music. The foreshortened Michelangelesque figure in red conte implies the experience of floating within the belly of the whale. These images may refer to The Book of Jonah from the Hebrew Bible, but in any case, they render a contemporary, even feminist, interpretation of that Biblical story. This is exploratory, preparatory drawing at its best. Julie Gearan’s compositions create a world of their own, liberated from Jonah’s narrative and from traditional concepts of figure drawing.

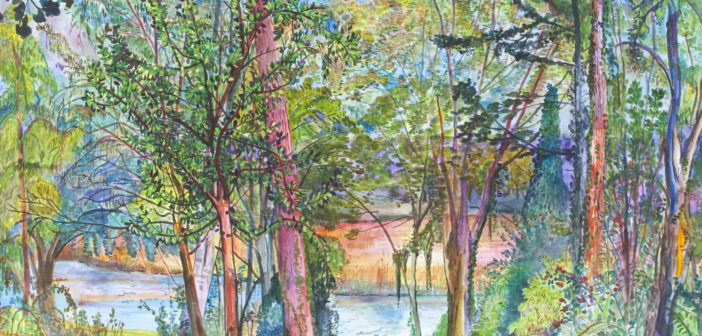

Nancy Friese, September on Lieutenant River

Nancy Friese’s gigantic watercolor, mounted on a stretched canvas is part of an ongoing series of monumental watercolor paintings that the artist has been developing in the past few years. This work extends a brilliant invitation into the natural world, which at once overwhelms and hypnotizes the viewer, who, quite literally, cannot consider the whole painting at once. One reads this painting in terms of poetic stanzas leading from the top down or from the bottom up. Treetops penetrate the empyrean, the very highest of realms in the form of fire, ether, or light in Aristotelian terms, a height so lofty that it transcends the space of Friese’s terrestrial composition. Sunlight emanates horizontally from a dimming white orb, and local color, as in so much of Friese’s work, is used expressively. We know she saw all of these things, but are such colors really visible to the human eye in nature? The answer is yes, and the fact that so many brilliant colors exist en plein-air and in the same single painting makes their observation no less rigorous or prudent. The river itself rushes through a narrow horizontal zone as if seen by accident. This landscape is more compulsively dotted and scrubbed with striations than in Friese’s earlier works, and the earthly, human-made pathway to the river is composed in a splendid rocaille of colored shadows and pebbles.

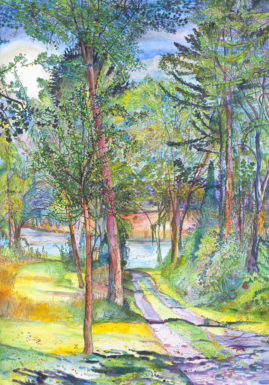

Nancy Friese, Rim of Sunlight and Trees

Those of us who have been following Friese’s work for the past fifteen or twenty years will observe a new profundity in her recent paintings. Deep feelings of nostalgia, longing, and even fear are plumbed and rise to the surface from the abyme of the natural world. If her earlier landscapes tended to metaphor, with say, a big sky dominated by clouds that could have been composed by Beethoven, some of the new works by Friese go beyond painterly description into a less conscious and perhaps more hidden place in the painter’s psyche, or as Sigmund Freud would have called it, her soul. This is evident in Friese’s oil painting Rim of Sunlight and Trees recently installed at The Pavilion at Grace, a luminous modernist building designed for Grace Church by the Connecticut firm Centerbrook Architects in Providence. Friese has flung open a great window onto the natural world in her exalted landscape, which is one of her most splendid to date.

In Contemporary Master Drawings, Tompkins brings together her roster of local and international artists to showcase their technical mastery, but it is their contemporary points of view about personal nostalgia, and the genii of particular geographic places, that give this show its common theme. Landscapes, seascapes, and city scenes are subject matter, for mesmerizing explorations of the earthly, dream-based, and mythological.