January 23, 2006

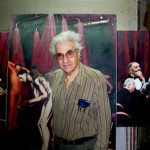

The initial phone call came back in December. An invitation from the artist Arnold Trachtman to come view a large triptych “Cabarett, 1927” which he worked on from 1993-1995 but had just finished. It was taking up a lot of room in his attic studio and he was soliciting curators, critics and friends to come see it before putting it into storage along with a dense clutter of works with mostly social and political themes dating back to the 1960s. He was anxious to make room in the studio.

That was right about the end of the semester and exams which is the worst time of year for professors. So I told him to get back to me after the Holidays when I would still be on break. He didn’t. Instead, the call came from his wife Joan just as I was preparing to launch a new semester; for professors, the second worst week of the year. Add to that a brutal virus/ fever that had knocked out a week of the break ending with an overnight in the hospital. So I was not in the mood for a studio visit. Then Arnie called, and frankly, I was abusive in response. But humorous and good natured as I agreed to come on Saturday but with some resentment as I would have been much more free and relaxed the week before. I promised that my mood would change.

Well, somewhat, but not entirely. Arnie can be stubborn as a mule and frustrating to deal with. During the Democratic National Convention in Boston a couple of summer ago, I included him in a group show. He showed a vintage triptych “Win One for the Gipper” which was a send up of a prior Republican convention with all its phony hoopla. A hilarious and insightful piece. I recall discussing it with him as we struggled to identify some of the now forgotten politicians it depicts. Which is the problem with topical art. It fades like yesterday’s newspapers. But Arnie is an individual who never forgives and never forgets. He reminded me that over the years I have been one of the few critics who ever had anything nice to say about his work. Going back to my first coverage circa 1968 when he showed at the Community Church and Art Center. I was also doing political art and we showed together “Four Socially Concerned Artists,” around 1970, in Seward, Nebraska. One of the other four was Peter Saul from Chicago.

To some extent I continue to make and think about political art. After 9/11 the next couple of years were spent processing that experience and I showed the resultant work on several occasions. That spilled out into an ongoing concern with the theme of war and man’s inhumanity to man as well as Bush and his warmongering. But my ideas and approach to political art have filtered and changed a lot both in terms of my own practice as well as that of others.

The turning point occurred thirteen years ago when I bought a three decker house in working class, largely Latino and immigrant, East Boston. That meant packing up after some 25 years of living in the People’s Republic of Cambridge. Many of those years were spent residing in the Murder Building on University Road in Harvard Square. Musicians and artists like Peter Wolf, Ed Hood, and Magic Dick lived in the building which had been the site of several spectacular murders including a victim of the Boston Strangler as well as a ritual killing of an anthropology graduate student from Harvard. We hung out in the cafeteria Cardell’s and argued art and politics at the Patisserie. It was the era of Vietnam and its aftermath so artists like Arnie were comrades in arms. Then I moved, became a home owner, got married, got straight and started morphing socially and politically.

Today, I feel like one needs a passport to make that rare visit to Cambridge. There should be guards posted on the Mass Ave Bridge when you pass through Checkpoint Charlie from Boston to Cambridge. “You are now entering the game preserve of hippies and radicals,” the guard would say while stamping your visa. “Do not pet, feed, or talk to the natives or you will be shot.” Something like that. But, truth is, the Square ain’t what it used to be. The cozy hangouts are gone and the Harvard kids are mostly young Republicans. There hasn’t been a decent protest in years. The Murder Building has gone condo.

So there we were in Arnie’s cluttered home and attic. Once again, revisiting the Weimar Republic. His triptychs have often made me think of those of Max Beckmann. More for their content than style. The actual painting technique is harder to pin down. It certainly does not reflect his professors Lawrence Kupferman, a modernist, to the conservative Patrick Gavin and Otis Philbrick at Mass Art from which he graduated in 1953. After a stint in the army, posted to France, he earned a Master’s degree at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1955-1958. Despite the training he is more or less an autodidact. The concern was less with the manner and style than with the content. He has had a compelling and burning agenda that guided and consumed him. But knowing the work since the 1960s I am impressed by the trajectory that has become ever more skilled and refined.

Rather harshly I taunted him. If this is 2006 why are you dealing with 1927? “Because the issues have not been resolved,” was his response. “Why not Bush and his gang,” I demanded? There were some small but wonderful drawings of Bush, Cheney, Rice, Ashcroft pinned to the wall. “Why are you dwelling on the past and letting Bush off the hook,” I demanded? His response was that he was done with topical painting. The works get seen once or twice and nothing sells. Over the years, he is now 75, I asked approximately how many pictures he has sold? “About a dozen,” was his answer delivered with a great laugh. “But the museums of the world are filled with political art like Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, Sue Coe and Georg Immendorf,” I pointed out. “I paint better than Golub,” was his comment. So it is a matter of fame and marketing.

Over the past month about 30 people have come to see the work by appointment. That includes art historian Pat Hills who has shown and written about the work. Gallerist Arthur Dion of Gallery Naga who makes it a point to be on top of Boston painters. Nick Capasso, curator for the DeCordova, which bought a painting a couple of years ago that is now on view in the permanent collection. And, the famous radical professor, Howard Zinn, a friend of many years.

They came to view a compelling and riveting triptych. What took so long was the center panel which represents a group of men showering. Clearly it is a reference to the Death Camps. It didn’t work and he later added the lower right vignette of a boy seen from the rear, a yellow star sewn to his back, carrying a torah. The panels to the left and right represent vintage views rendered from found photographs. On the right is a group of diplomats seated around a table with wine glasses, smoking cigars. “Who are they,” I asked? But he could not identify the participants rather it was a reference to the endless negotiations that led up to war. On the left is a panel that depicts a side show. There are musicians drawing a crowd and behind them banners promoting circus acts. One cartoon advertisement shows a man with enormous ears and a Hitler moustache. “Is that Hitler,” I asked? But it was not; seems that moustache was in style at the time. Of the musicians the man playing a recorder is Brecht. In earlier work he did a remarkable series of small portraits of leading figures of the era from Brecht to Kafka, the Kaiser, generals, politicians, and Wagner as well as others now mostly forgotten.

In addition to the political paintings, over the years, Arnie has done some wonderful still lifes of musical instruments dedicated to the famous jazz musicians who played them. He has also painted terrific expressionist views of Cambridge. Surely these would sell in the right context. But he shrugged that they were shown in a small Cambridge gallery in the 80s and nothing sold. I have included them in some shows I curated like “Jazz” for the old Boston Visual Artists Union and a traveling show I organized “Be Still Dear Art.”

He did show on Newbury Street at Nasrudin Gallery but recalled with a shrug that the gallery closed right after that. Sinclair Hitchings, who has recently retired from the department of prints and drawings at the Boston Public Library, bought 60 works on paper. And he is included in a portfolio “Art Against Racism and the War,” printed by Impressions in the late 1960s, which was sold to a number of museums including Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

There have been several important group shows that included his work such as “As Seen from Both Sides: American and Vietnam Artists Look at War,” 1991, curated by David Thomas. That show toured both the US and Vietnam. Another major exhibition was “Witness and Legacy: Contemporary Art About the Holocaust,” curated by Steven Feinstein, 1995, which traveled after being launched in St. Paul, Minnesota. In the context of these large thematic group shows Arnie has always stood out. But, truth is, it is the kind of work that collectors are not inclined to hang in their living rooms. With the vantage of time, when hindsight will be 20/20, curators may discover that there have been few more persistent and insightful chroniclers of the social and political events of our time. His Vietnam era images, for example, may come to be regarded as national treasures.

But what about Bush? I continued to torment him as we shared a lunch prepared by his wife Joan. How can you let him off the hook? He shrugged. Maybe. Right now he is glad to finish work on 1927. Arnie, now more than ever, we need you. Soon the studio will be clear and it will be time to begin again. Bush.

All images are courtesy of the author.