Bryan Christie’s solo exhibition, Every Angel is Terror, offers tangible evidence that the categories we create for the sake of language—art, science, religion, poetry—dissolve at a point of convergence. On view at Matter & Light, this exhibition grasps at what is sought out by scientific inquiry and spiritual exploration alike: the unseen, unknown, and unnamable. No less artist than alchemist, Christie combines his knowledge of digital illustration, human biology, spirituality, and art practice into works that bring the immaterial into the material realm.

At first, Every Angel is Terror seems like a painting show, however, Christie’s canvases soon waver in and out of familiarity. The imagery is decidedly bodily—redolent of blood and viscera—yet abstracted and heightened by saturated blues and luminous reds. The show’s eponymous work on the far wall, Every Angel is Terror, has the effect of yanking me in by the collar. At once daunting and docile, is aptly named. The five-by-four-foot piece bears a smoky apparition resembling a demonic head with wispy “horns” that appear almost airbrushed. Loosely symmetrical, it looks like a cross between a Rorschach test and an MRI scan. In the center of the lower third (where the demon’s “mouth” might be) an incandescent orange glows with the intensity of a furnace into a blush of shadowy reds. Faint outlines of anatomical forms swim beneath a smooth surface which has the yellowish tint of a rawhide bone.

“Sifter of Dust”, Silk and encaustic on panel, 24” x 12”

Courtesy of Matter & Light

If you’re having trouble picturing this work, it’s because I’m having trouble describing it. Christie’s technique is highly specific, so much so that I feel like assigning it a genre would be automatically inaccurate. The pieces are actually composed of digital images printed onto layers of silk and embedded in wax. Christie’s professional background is not in painting or studio practice but in scientific illustration. As the founder of his own scientific illustration studio, Christie has produced images for such publications as the New York Times, WIRED, and National Geographic. The same software that he uses to render illustrations for his clients is central to the work in Every Angel is Terror.

All of the work in the exhibition is created through a unique process that Christie developed about five years ago. It starts on the computer where Christie poses a model of an anatomically correct human figure in 3D space. Using the software’s camera tool, he takes a series of snapshots—what are essentially virtual MRIs—of cross-sections or slices of the model. With anywhere from three to twelve of those images, he creates a composite in Photoshop where he can arrange them on a grid and adjust the colors. Each layer of the composite image is then printed out onto its own sheet of silk. After the digital work is complete, he covers a wood panel with encaustic and heats it until it’s liquid smooth. When the encaustic cools, he lays down the first layer of silk and reheats the wax so it seeps into the fabric. When the wax cools again, he stacks on the next layer of silk and repeats the process.

What’s more striking than Christie’s technique alone is his execution of it: his ability to seamlessly marry digital technology and ancient materials. The pieces feel neither computer-generated nor digital in a way that might connote “inhuman”. The wax has an undeniable fleshiness to it and there is an added intimacy in knowing what it would be like to touch it. This is especially true of the works with more layers like Sifter of Dust which has twelve.

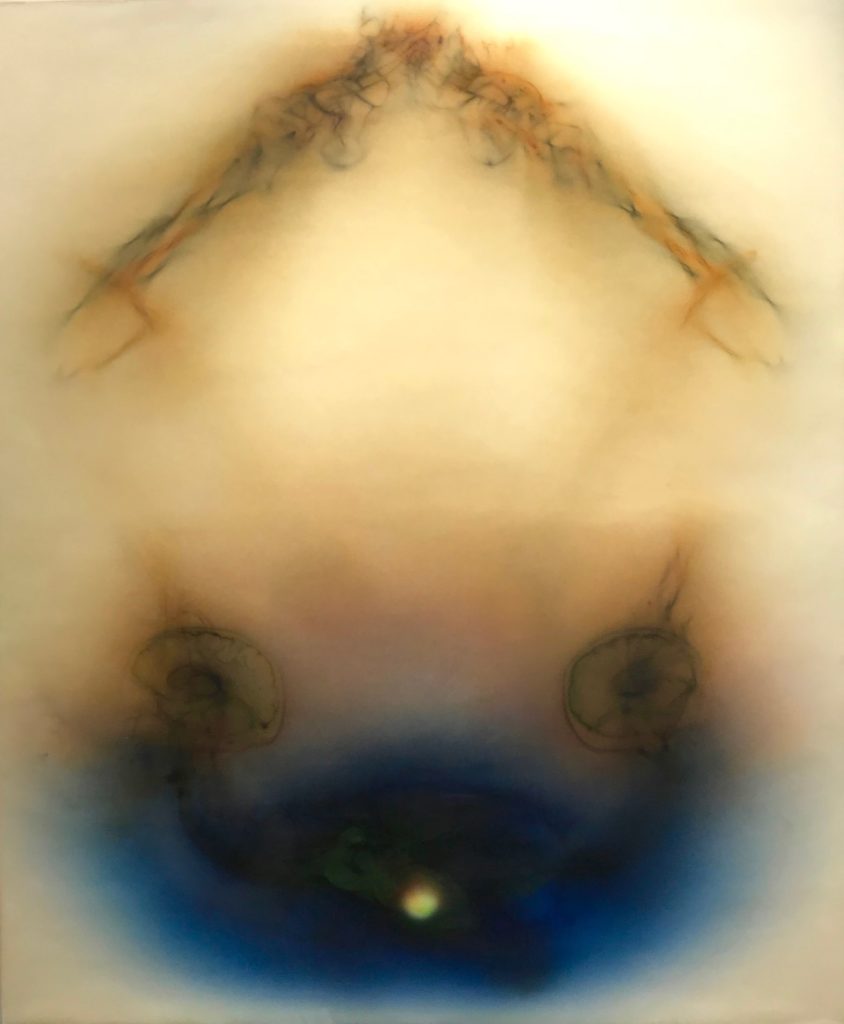

“Of Your Presence Just Passed”, Silk and encaustic on panel, 36” x 30”

Courtesy of Matter & Light

Sifter is much smaller and quieter than most of the other pieces. Vertically oblong, there is a soft, vaguely face-like form that peers through the milky encaustic in which it is submerged. Of course, it is not really a face: the reddish strands that could be hair are in fact parts of the lungs, liver, and intestines. The “eyes” are a cross-section of the uterus. The way in which this image is at once present and obscured, like veins barely visible beneath the skin, says something about the humanity of Christie’s work: Despite having unprecedented access to the body, the show does not claim to have any more answers about the human anatomy than Rembrandt’s, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicoleas Tulp or Michelangelo’s, Pièta.

Luminosity is what held my attention moving through Every Angel is Terror. Not every work achieves the same inner radiance, but when it happens, it seems as if the colors are being lit from the inside. A pinhole of yellow beams through a dark pool of ultramarine in Of Your Presence Just Passed. An orb of celestial red burns at the core of Slumbers of Attraction. These moments, no doubt a mixture of practice and happenstance, do not call for analysis but simply appreciation. One gets a shiver of the divine.

Bryan Christie's Every Angel is Terror is on view through March 31 at Matter and Light Fine Art, 63 Thayer Street, Boston.

1 Comment

Excellent commentary!