The new year brought a story that seemed to be a long time coming. A group of Facebook architects harshly criticized the company for its involvement in the spread of fake news and voiced their concern that the company has “created tools that are ripping apart the social fabric of how society works.” They cite, in part, Facebook’s ad-driven model, that created a portal to draw in and keep users.

Into this growing public discussion surrounding our affinity for screens enters Screens: Virtual Material at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, a group exhibition with very few digital screens. The show asks viewers to think critically and broadly about screens and their effects on space and interaction. Though most of the objects displayed are not digital, they engage in the dialogue concerned with how screens isolate and mediate our lives. Different objects elicit different responses, but we cannot escape that each one filters and partitions our reality. Even when we feel connected to others through our devices, are we not isolating ourselves from our immediate surroundings?

Screens is as much a visual experience as it is a physical one. From Liza Lou’s Maximum Security (2007-2008), Marta Chilindron’s Cube 48 Orange (2014), to Matt Saunders’s Two Worlds, and a Half (2016-2017), visitors can weave in and out of much of the work on display and view it from multiple angles. We are simultaneously pulled in and directed by each object.

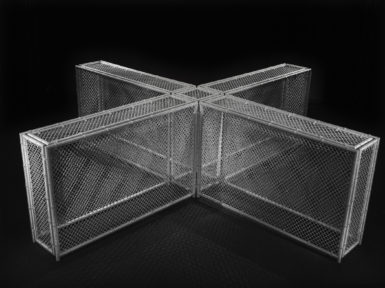

Liza Lou, Maximum Security, 2007–8, steel, glass beads, 276 × 276 × 80 inches, Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong, Photo by Tom Powell.

Liza Lou’s striking, large-scale fence structure calls visitors from the landing into the gallery. Maximum Security, a chain link fence covered entirely in tiny silver beads, simultaneously dazzles and deflects. Like a functioning chain link fence, it is semi-permeable, dissecting space while not completely obstructing views. The coating of beads, however, makes it a bizarre object - while the fence’s abstracted arrangement seems to impose, it speaks more strongly as a decorative object than a real barrier, especially since visitors are separated from it by stanchions. Lou created Maximum Security in response to the conditions at Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, among other U.S. prison complexes. In this context, we are reminded how this simple metal barrier can foster detachment and isolation, and, simultaneously, how it can offer a false sense of security.

Liza Lou, Maximum Security, 2007–8, steel, glass beads, 276 × 276 × 80 inches, Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong. Photo by Rick Mansfield Jr or Anchor Imagery.

Where Maximum Security appears solid, Chilindon’s Cube 48 is fluid. The shape-shifting, bright orange polycarbonate wall can measure 48-inches square or, fully expanded, match the length of a New York City block. Like Maximum Security, Cube 48 is made up of smaller units; however, it is flexible, moldable to almost any space. Both works are whimsical in material, but Cube 48 does not present an easy way to navigate its orange-hued arrangement. It is a temporary barrier, something that can bend to a person’s will and transform the way space is navigated and understood, based on its configuration.

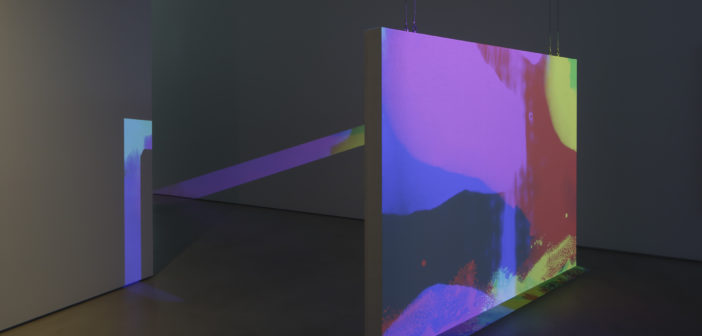

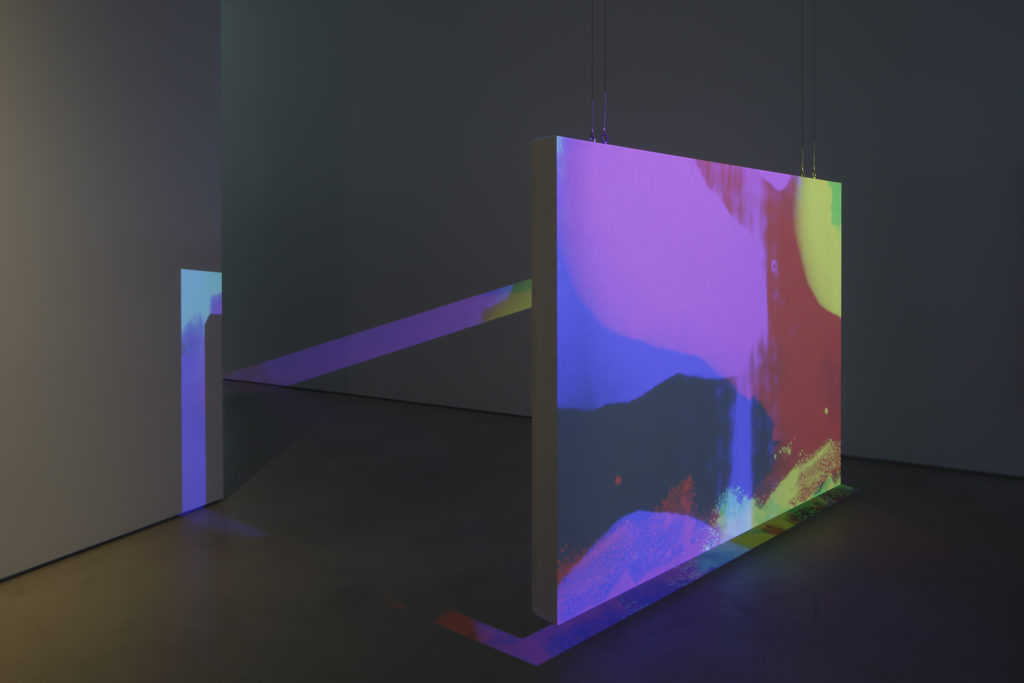

Matt Saunders’s Two Worlds also deconstructs space in an immersive way. Occupying the back third of the second gallery, it is an installation featuring three animated films projected on three separate screens, accompanied by two gelatin silver prints mounted on a wall in between two screens. It is a wonder to stand amongst these three animations, composed of smaller painted or drawn compositions linked together in a looping film. Two of the films are housed in facing alcoves, while one, which appears to be a canvas, splits the area and faces a window. While the alcoves are dark, the canvas facing the window, subject to natural light, is obscured. The animations appear to be stop motion in nature as delicate figures and mesmerizing colors dance on their respective screens, each oblivious to its siblings, but connected thematically. Through these separate “realms,” Saunders creates a cohesive, spellbinding expanse.

Matt Saunders, Two Worlds, 2016, installation in 2 parts; 2 high-definition animated films (color and black and white, silent), 12 minutes, 24 seconds, and 8 minutes, 16 seconds, loop, on 2 screens, Installation view, Blum & Poe, Tokyo, 2016, © Matt Saunders, Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles / New York / Tokyo, Photo by Keizo Kioku.

In the same gallery as Two Worlds, Brian Bress’s video-based work attracts the most attention. All three screens show Bress’s cartoon-like characters engaging in various interactions with the barrier immediately in front of them: the screen. In Striped Angles on a Norfolk Island Pine and NOON NOON (both 2015), the characters’ movements are unpredictable and deliberately slow, at times appearing as if they are reacting to visitors. The longer visitors watch, the more it becomes apparent that the characters are interacting with the plane in front of them, appearing to dismantle the screen separating the visitors’ space from their own. Of course, despite the engaging and temporary illusion, we are reminded that the high definition screen is not a looking glass. Fun to watch, Bress manages to merge visual wittiness and complexity in a way that draws one in from all corners of the gallery.

installation view, Screens: Virtual Material, deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum

In this array of literal screens, Penelope Umbrico’s Out of Order: Bad Display (100717) (2017) stands out. In a display of prints, LCD screens and Plexiglas, Umbrico presents a narrative about how we reflect distorted versions of ourselves both online and in person. In the gallery, visitors can see themselves in the reflective material she used for her installation. Conceptually, the artist culls the images of broken screens from a library she has amassed from Craigslist and other sites. These vignettes are abstracted, and combined with other clear and reflective plastic, form a teetering conglomerate that is like a graveyard full of obsolete technology.

Josh Tonsfeldt’s Untitled series (2017), echoes Umbrico’s fascination with the materiality of television screens. Tonsfeldt transforms parts from discarded monitors into ethereal light-catchers that project off of the wall and distort perception. The work’s effect is amplified by natural light and appears to change shape as visitors move around it. Unlike Umbrico’s reflecting Out of Order, these abstracted screens obscure.

Marta Chilindron, Cube 48 Orange, 2014, Twinwall polycarbonate, Courtesy of Cecilia de Torres, Ltd., New York, Photograph by Clements Photography and Design, Boston (Installation view at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum).

Visitors are drawn into each work differently. Often, it is the object’s visual characteristics that attract, and the spatial effects are secondary - our perception of space is manipulated without our immediate awareness. Like Lou’s sparkling fence structure or Tonsfeldt’s manipulated monitors, our digital devices are designed to draw us in through the visual. Our undivided attention can be lucrative, and moderating our experience in a way that feels authentic, as Facebook and Screens have done, is crucial for sustainability. As participants in this mediated reality, we should be just as aware of the phone screen as we are of the fence.

Screens: Virtual Material is on view through March 18, 2018.