Joe Bradley’s mid-career retrospective at the Rose Art Museum, on view through January 28, opens with a wall of drawings that may convince you that the survey stretches back to adolescence. A cartoon dog’s head floats on a largely empty page like an abandoned doodle from a teenager’s notebook. Geometric patterns are colored in on cheap, shriveled graph paper and memo pads. They look like ideas torn out of a sketchbook without any fuss over archival materials or awareness of future value. The drawings are surprisingly recent creations though, and valuable works by an artist in his early forties who has already achieved enormous market success. Looking at the drawings, I wondered are they good? Bad? Dumb? Funny? Are these even the right questions? Is this an artist cynically pantomiming free-spiritedness or earnestly plunging into a mindset where art demands an urgency that far outstrips concerns of economic potential or conventional taste? Like much of Bradley’s work that is purposefully raw and unresolved, there are no easy resolutions or answers, and you can start to wonder if the joke’s on you for even taking it this far.

Joe Bradley (installation), 2017. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University. Photo_ Charles Mayer

These drawings are like a loose map or legend to most of what unfolds next in an exhibition that clusters a little over a decade of Bradley’s work around a few primary threads. In his “Schmagoo” paintings, a term Bradley thinks of as shorthand for “Primordial Muck,” Bradley scrawls cartoon hieroglyphs like Superman’s iconic logo in imperfect lines of grease pencil on white canvas. In another series, he arranges monochrome canvases to create modular paintings suggestive of clunky, looming totems with heads, torsos, and legs (imagine Ellsworth Kelly stick figures). In much less pristine work, Bradley cuts up, stitches together, and walks all over paintings on his studio floor to create scarred, heavily worked abstract expressionist style paintings. Chalky, opaque geometric compositions in red, yellow, blue, and black fit in between the more deliberate modular paintings and looser abstract paintings. The show also includes recent forays into sculpture like Sculpture for Billy Hand (2017), a large pink rectangular sculpture that sits like a narrow aluminum barrier in the middle of the exhibition. It’s Pepto-Bismol minimalism helping it all go down, or maybe causing indigestion.

Joe Bradley, Mother and Child, 2016. Collection of Larry Gagosian. Image courtesy of the artist

The individual drawings and paintings that form each series are most effective as a whole to demonstrate Bradley’s ability to constantly skirt the line between abstraction and representation, informality and formality, finished and unfinished, impurity and purity, irony and sincerity, play and purpose, heroic and comic, high and low, amateur and professional, and just about any other aesthetic duality. The wall text about Bradley’s drawings states that “for Bradley, the best work comes with either freshness or exhaustion, and getting to either place means feeling some degree of comfort in his situation.” The irony of this is that the end result may leave us, the viewer, in an uncomfortable place on slippery terrain.

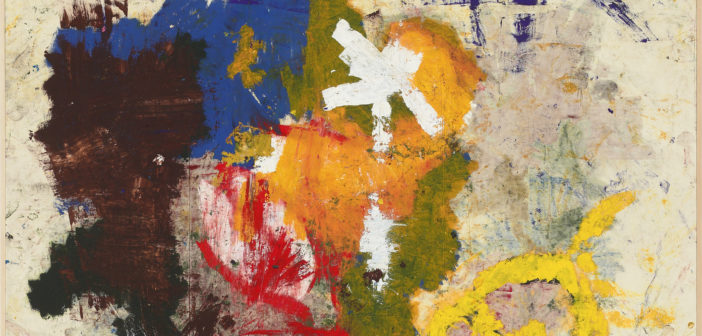

Joe Bradley, East Coker, 2013. Private Collection. Image courtesy of the artist. © 2017

There is a progression for Bradley as he moves from his pared-down modular paintings and simple line drawings to his messier abstractions, but if the dates were taken away I cannot imagine anyone could guess the chronology. Ten years of work shows no evolution in touch or sensitivity, just shifting formats that could be returned to at any moment. A lover of underground comics in high school who discovered art history at RISD, Bradley’s primary goal may be to return to or never lose the immediacy and directness of the first way he made a mark. This is a refreshing tendency as Bradley brings the vaunted lineage of modern painting down to a very personal, human level. Nothing is pristine, and everything enters the mess of his studio floor. Bradley is quoted as saying that painting “is just a very human activity that takes time,” and he describes his process as “building damage into the work.” As personal excavations, his canvases remind me of the way street posters are ripped or torn away over time, or how chewing gum might collect under a school desk chair – something that could be weirdly beautiful, disgusting, tactile, and not entirely formed through conscious intent.

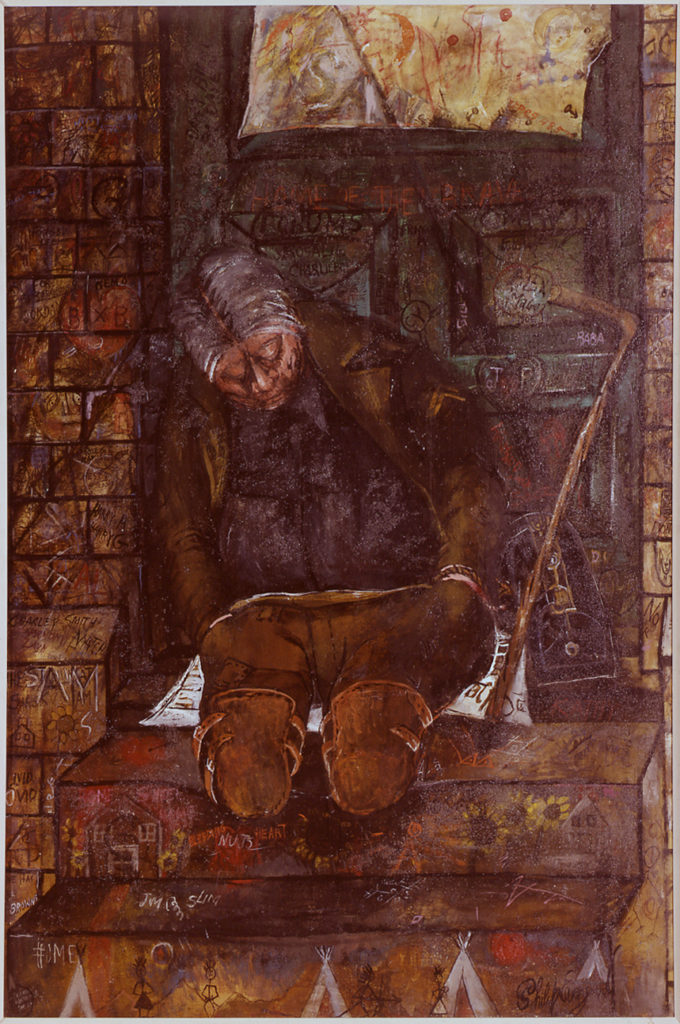

Philip Evergood, The Forgotten Man, 1949. Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University_ Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harris Klein, New York. © Philip Evergood

The exhibition at the Rose is complemented by a small show of works selected from the museum's permanent collection by Bradley. They are a prelude to his retrospective, and many of the picks revel in mark making with tactile surfaces. Marisol’s wooden cat stares intensely like a cartoon version of an Egyptian votive with a coat full of rough chisel marks. Larry Poon’s acrylic painting, Jazio, almost melts off the wall, and Claes Oldenburg’s Tray Meal displays delightfully alien-looking, lumpy food. In a couple of less tactile works, a blurring between abstraction and representation continues as the human figure is a building block in abstract compositions. Reginald Marsh’s Coney Island Beach #2 shows a dense pile of tangled bodies that dissolve into an all-over pattern. Phillip Evergood’s Forgotten Man painting depicts a destitute amputee with his slouched over body at one with and, almost camouflaged by his surroundings, a grimy, graffiti-filled stoop.

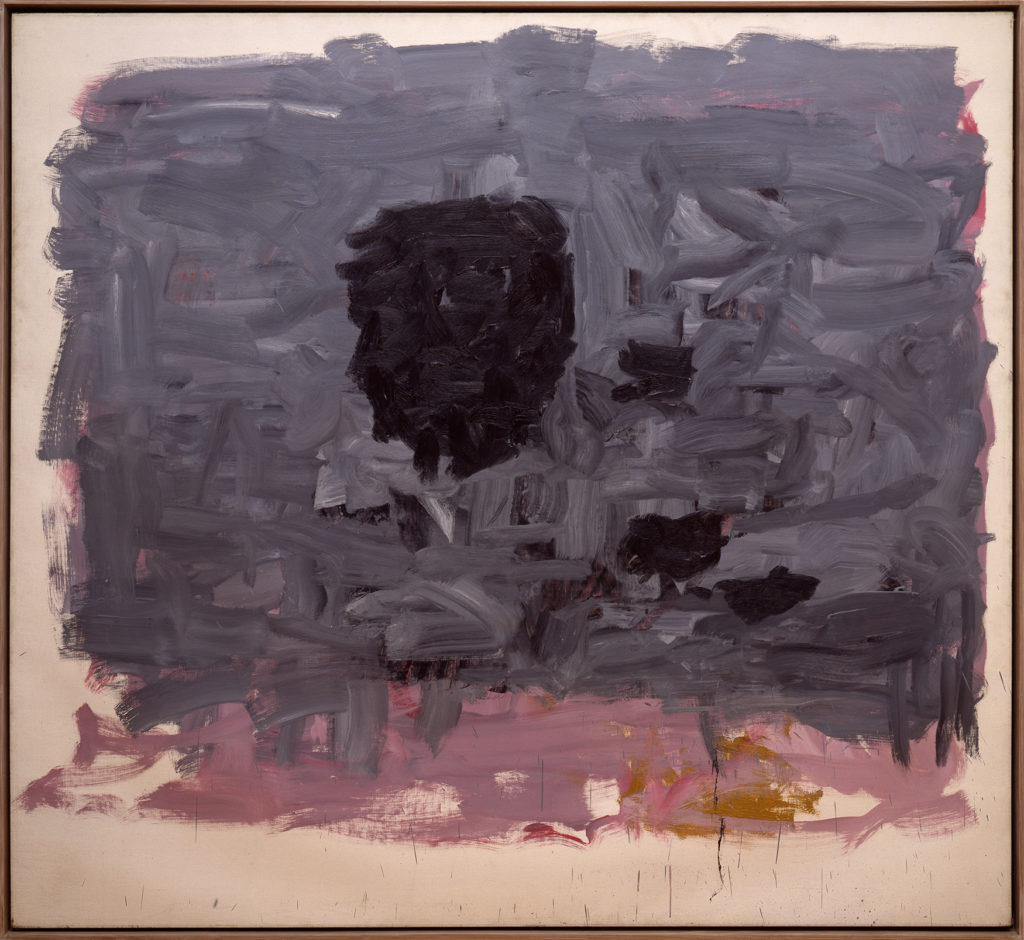

Philip Guston, Heir, 1964. Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University_ Bequest of Musa Guston. © The Estate of Philip Guston

These works offer little clues into Bradley’s artistic proclivities. Perhaps the most direct connection is a knockout painting by Philip Guston from 1964, completed three years before Guston shifted to cartoonish and personal subject matter. In Guston’s Heir, a circular black void sits over fleshy marks of dark grey that blot out a pink underpainting. Looking at it, I wonder if Bradley is Guston’s heir or at least, like many contemporary painters who admire Guston, aspires to be. Guston has passed down the idea that it is ok to throw out established ideas of good taste and norms of serious painting to explore something personal and visceral with a sense of tragic absurdity. Guston’s complex depictions of life in the studio also gave permission to turn the subject matter back on oneself, but in Guston’s case, this was married in complicated ways to a social and political conscience, depicting Ku Klux Klansmen and a pervading sense of dread. I see this struggle in Bradley’s work as I imagine him in the studio walking back and forth over canvases, cutting, stitching, and seaming to embrace damage, discordance, and sometimes letting rare moments of balance or resolution remain. In relation to Guston, Bradley’s struggle feels lighter and more precisely aimed at the cumulative weight of art history. Instead of being defeated by the nagging sense that everything has been done, Bradley continues the avant-garde tradition of trying to rediscover primary impulses. He wades in the “primordial muck,” which includes any piece of visual culture you can imagine, as he grapples with what seem like ancient materials: paint, canvas, and time.

2 Comments

Your insights are refreshing as are Bradley’s quotes. Thanks for the effort!

Thank you, Robert!