“The ‘21st-century naturalist,’” curator Ruth Erickson explains in an introductory text to the exhibition Mark Dion: Misadventures of a 21st-Century Naturalist currently on view at ICA/Boston, “investigates nature as part of culture and society rather than separate from them—exploring how folk tales, hunting stories, movies, biology classes, advertising, and every discipline and industry construct their own versions of nature.” Instead of studying nature, the 21st-century naturalist studies us, scrutinizing the systems we create to understand our place in the world. In his role as a 21st-century naturalist, Mark Dion has amassed a body of work which includes a menagerie (both taxidermied and live), colorful household objects, and replicas of municipal laboratories.

Considering all of the interlocking roles and relationships in Dion’s work is daunting, but many of the lenses Erickson identifies can be grouped into broader themes. Chief among them, of course, is natural history and the dominant role humans assert over nature—Dion does not shy away from asking questions about the implications of our actions in relation to the natural world. Then, there is the self-referential notion of museum work and its origins in the European mode of collecting. Finally, collaborating with women artists, Dion also questions traditional gender roles and stereotypes. Some pieces offer a playful perspective meant to spur conversation, while others rely on shock value to make us pause.

Mark Dion, Cabinet of Marine Debris, 2014. Wood, glass, metal, paint, assorted marine debris, plastic, and rope, 113 x 84 x 32 inches. Collection of Martin Z. Margulies, Miami. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. © Mark Dion

Born and raised in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Dion’s affinity for artifacts, specimens and samples was fostered by his New England upbringing. Many works deal with the ocean and our relationship to it, such as Cabinet of Marine Debris (2014). An unassuming grey cabinet holds anonymous plastic bottles and other colorful trash items collected from the ocean. Dion displays the items in a fashion reminiscent of how one displays the finest china, bestowing them with order and underscoring the allure of their various form. Though the visual impact of the work is blatant, the allusions it makes to the impact of our shared careless attitudes towards the environment are more subtle.

Humans often turn to classification to assert dominance over the natural world. The Department of Marine Animal Identification of the City of San Francisco (1998), plays with this idea. During an “urban expedition,” Dion gathered fish from the city’s Chinatown markets and placed them in jars as wet specimens. During the original installation, the artist wore a lab coat and “classified” the sea creatures by referring to books and using his best judgement. Liberated from peer review and the rigidity and rules of scientific work, Dion borrows and molds the trappings of these systems to question the authority of the lab coat. He also critiques our methods of labeling and analyzing nature—systems constructed over a century of classification-based science, but which still give semantic meaning to how we understand the world.

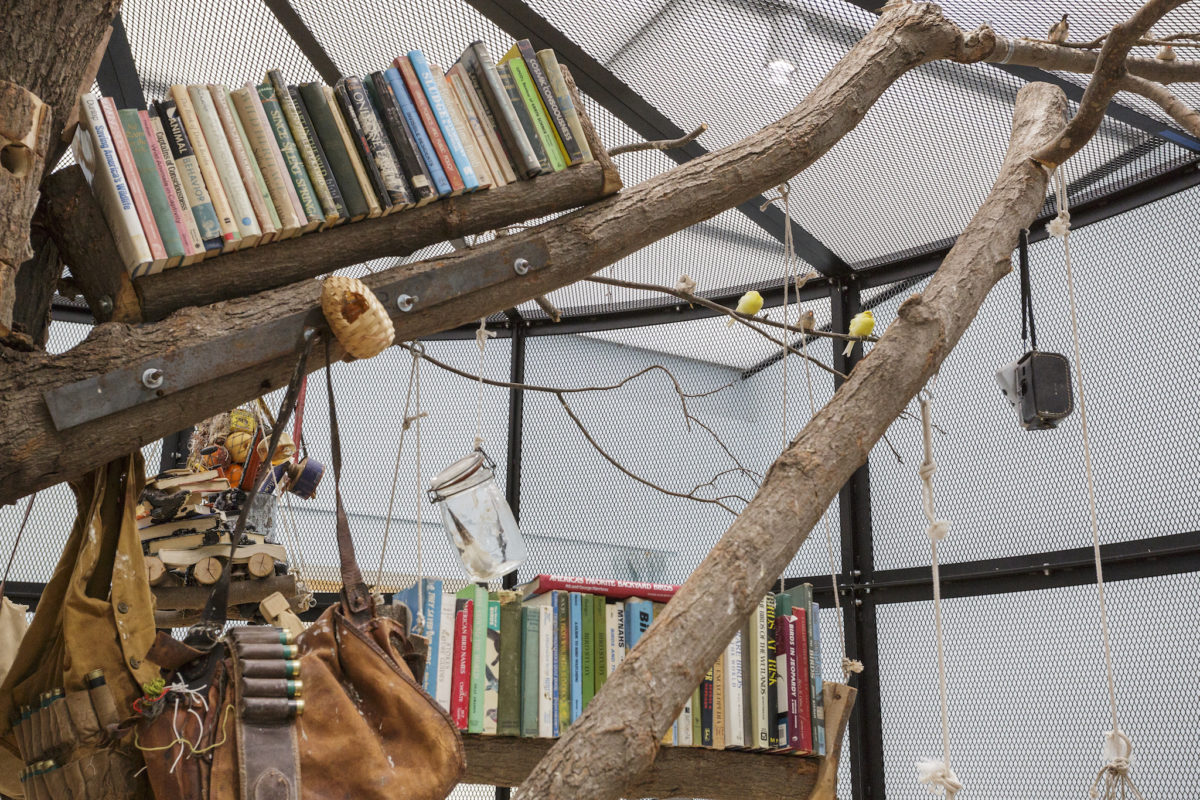

One of the most memorable works in this vein is The Library for the Birds of New York/The Library for the Birds of Massachusetts (2016/2017), a room-sized bird cage. Audible from nearby galleries, the cage contains a tree, live finches and canaries, and books on subjects that vary from birdwatching to Aristotle. The birds defecate on the books supplied to them, indifferent to the systems we impose to understand them. One can’t help but laugh as the birds flutter and chirp in this elaborate cage filled with targets for shooting, decoys for hunting, and titles such as Ecology as Politics.

Mark Dion, The Library for the Birds of New York/The Library for the Birds of Massachusetts (detail), 2016/2017. Steel, wood, books, living birds, and found objects, 138 × 240 inches (350.5 × 609.6 cm). Sammlung Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich. Photo by John Kennard. © Mark Dion

In a nearby gallery is Killers Killed (1994-2007), a jarring piece in which taxidermied animals, all “r-selected species” such as cats and rats, are smothered in tar and hung up on a tree. The composition recalls Jacques Callot’s etching La Pendaison (The Hanging) from 1633. The print, which shows those judged as criminals hung for their trespasses, is eerily reimagined in Dion’s sculpture as a group of what he calls “detested and persecuted” animals trapped in deadly tar. Dion comments on the effect we have on the environment—humans introduced these species into new habitats, but grew to detest them as they thrived and competed with native fauna. Our desire to control our environment has real consequences, both immediate and delayed.

Proceeding through the galleries, we are continuously confronted with the concept of collecting. It is critical to Dion’s artistic process. He draws heavily upon the tradition of the Wunderkammer, or cabinets of curiosities, as he did for Cabinet of Marine Debris. In the very first gallery, we are met with Toys ‘R’ Us (When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth) (1994), a replica of an imaginative child’s bedroom from the 1990s. Dinosaurs are plastered on the walls, roam the floors, and sit precariously on shelves. Dion freezes a cultural moment, commenting on how capitalism—and particularly advertising—can fuel our desire to obsess and collect, even at a young age.

Dion’s work also draws attention to the invisible labor within museums and historical institutions. Several displays in the exhibition were part of a collaboration between Dion and other institutions, including The Package (2006-11), in which Dion shipped boxes to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, only allowing staff to X-ray, rather than open, the packages. At the ICA, the boxes are stacked precariously atop wall-mounted lightboxes, which display the X-ray images. In a nod to Man Ray’s “rayographs,” the X-rays don’t actually shed much more light on the meaning behind the objects, but merely highlight their silhouette. If there is a narrative, we are not privy to it. On the one hand, this display lets us ponder the mysterious objects hidden within. On the other, it draws attention to the movement of objects in various shapes and forms in and out of museums, and acknowledges some of the behind-the-scenes work required to produce an exhibition. By highlighting the process of collecting, analyzing, archiving and conserving, Dion draws parallels between naturalists and curators, conservators, archivists, preparators, and so on.

Mark Dion, "The Package," 2006-11, lightbox, X-rays, and cardboard shipping boxes contains unknown objects, 40 1/2 x 115 x 4 inches. Collection of Paul Marks, Toronto. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. © Mark Dion

Gender roles and stereotypes are also examined. The Ladies’ Field Club of York (1999), a series of sepia-toned gelatin silver prints, presents “a group of female natural history enthusiasts” from what looks to be the late nineteenth century. Collaborating with the artist J. Morgan Puett, Dion reimagines the tradition of largely male-dominated field of natural history by creating portraits of female scientists. Dion and Puett encourage us to think about how little is known about women’s contributions to both the natural sciences and science, broadly. Compare The Ladies’ Field Club with Men and Game (1999), a substantial salon hang of 161 hunting photographs, in which a group of mostly men pose with their trophies. The photos, all collected by the artist, are meant for personal display. Like mounting the head of a wild animal on the wall, this photographic memorabilia signifies a dominance over beasts both large and small. Though hunting has long been associated with masculinity, this repetitive, dizzying display renders it foreign, like the effect of repeating a word over and over again until it loses its meaning. The longer we look, the faster the trope disintegrates.

Mark Dion, "Toys ‘R’ U.S (When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth)," 1994. Mixed media, dimensions variable. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo by John Kennard. © Mark Dion

During a talk shortly after the opening of the exhibition, Dion discussed a past project with the British Museum of Natural History. Like many of his endeavors, this was a large, multifaceted project that included fieldwork and excavation—performative acts difficult to translate within the limitations of the gallery space. Though 21st-Century Naturalist attempts to address this with two dioramas standing in for major public, site-specific commissions, it simultaneously draws attention to the experiential component of Dion’s practice that we miss without the artist or original work present.

The interactivity of the exhibition amplifies the idea of play, turning commonly-held notions on their head. In my two visits to the gallery, it seemed that visitors were both hesitant and excited to touch, enter and rearrange some of Dion’s world. This survey encourages visitors to go outside, look more carefully, and play doubting Tom every once in awhile. It also cautions us to be mindful of our place in the natural environment—if we insist on asserting control over the natural environment, we must also consider the ramifications of our actions down the line.

- Installation view, Mark Dion: Misadventures of a 21st Century Naturalist, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2017. Photo by John Kennard. © Mark Dion

- Mark Dion, After Neukom Vivarium, 2006 2017. Diorama model of existing public installation, Mixed media, Approximately 36 × 48 × 50 inches (91.4 × 121.9 × 127 cm). Exhibition copy. Photo by John Kennard. © Mark Dion

- Mark Dion, The Library for the Birds of New York/The Library for the Birds of Massachusetts (detail), 2016/2017. Steel, wood, books, living birds, and found objects, 138 × 240 inches (350.5 × 609.6 cm). Sammlung Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich. Photo by John Kennard. © Mark Dion

- Mark Dion, “The Package,” 2006-11, lightbox, X-rays, and cardboard shipping boxes contains unknown objects, 40 1/2 x 115 x 4 inches. Collection of Paul Marks, Toronto. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. © Mark Dion

- Mark Dion, “New Bedford Cabinet,” 2001, wooden-and-glass cabinet and dig finds, 104 x 74 x 19 inches. Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. © Mark Dion

- Mark Dion, “Toys ‘R’ U.S (When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth),” 1994. Mixed media, dimensions variable. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo by John Kennard. © Mark Dion