“May you live in interesting times.”

- Chinese curse

With the fate of the planet hanging precariously in the balance, there’s at least one thing about which we can all be certain: we are living in interesting times. While it’s not the sort of interesting any of us would have asked for, nevertheless here we are, and every academic discipline, and anyone who does anything in the way of cultural work in any field, is left with a nagging choice. It’s a choice of conscience, really, but also one of meaning. For above all, what any thinking person wants is to be engaged in something meaningful, to feel as though one’s life work somehow matters in the world. Times being what they are, what we face is this: business as usual, or change? Head in the sand, or course correction commensurate with the sense of urgency that surrounds us?

For those of us in the arts the issue feels particularly vexing, art’s role in culture having become increasingly marginal – and increasingly painfully so – over the last half century. Already in the throes of an identity crisis of sorts, visual art has been hit especially hard. But it’s not recoiled passively; in fact, something of a course correction has been underway for some time. With the profusion of hybrid practices, cross-disciplinary collaborations, and all manner of “post-studio” forms of social engagement emerging, there’s a discernible shift afoot in how artists are conceiving of our role in culture. While many of us feel called to action, others of us may have simply grown tired of talking to ourselves. (Indeed, after decades of self-imposed hermeticism underwritten by a language impenetrable to all but the initiated, it’s about time we got out for some fresh air.) Whatever the case, the move out of the studio and into the world marks a significant turn, and one that comes as a welcome relief to anyone exhausted with both the tropes of postmodernism and a formalism that never seems to tire of itself.

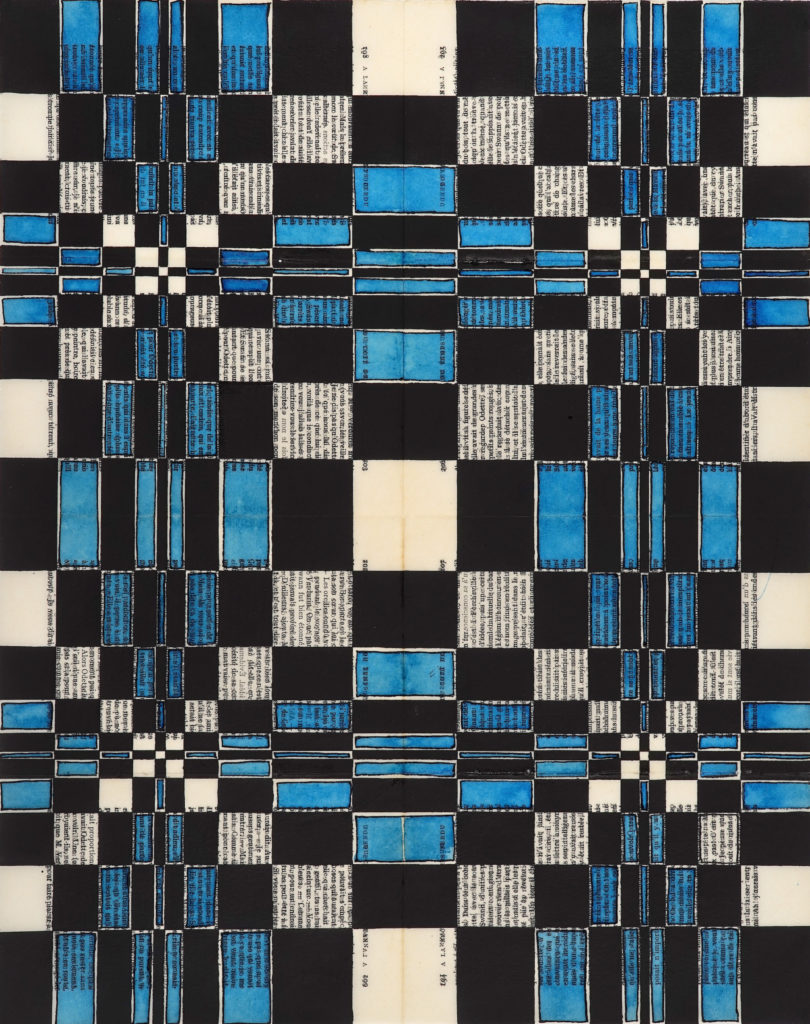

Oriane Stender, Untitled bookpage drawing (blue grid), 2016. Ink, beeswax on book pages. 18" x 14.

But as laudable as its motives may be, the post-studio shift is not without its perils. For it seems that absent some intensive soul-searching, art’s turn away from itself and toward the world may end up denuding it of the very thing that makes it worth bringing out there to begin with. One can see it happening already. In the looming emergence of PhD programs in the arts; in the nascent “sci-art” movement,[1] in which art is partnering with science to various ends; in the rise of the hyperintellectualized artist statement rife with language designed to invoke authority on high; in the increasing prevalence of the phrase “art as research”; and in the precipitous ascent of didactic art. In all of these can be sensed a distinct embrace of the discursive, and, implicitly, a subordination of the non-discursive. The professionalization of art we’ve witnessed over the last decades, in which an unapologetic careerism has turned artists into savvy business agents, hasn’t helped. But the deeper issue is what seems to be a growing distrust of what one may simply call poetry—art’s mysterious capacity for condensed expression—accompanied by a reach toward the rationalism that is its very antithesis.

Why the growing uneasiness about visual art’s “softer” dimensions? Since one doesn’t see this happening so much in literature, or dance, or drama, or film, it’s worth asking what it is about the visual arts that sets them apart. The particularly strained tone of much of the language in which visual art is packaged[2] suggests a discomfiting notion. Perhaps the hypertrophied rationalism in visual art might be a compensatory response to the public’s negative perception of our field. Indeed, of all the arts, visual art can seem the most superfluous, indulgent, trivial, and narcissistic. And very unfortunately, this perception even lurks within art itself. As anyone who’s been to an artist residency can attest, visual artists rank lowest on the hierarchy of respect. Writers, without exception, rank highest. It’s a complex issue, and one for which visual artists are not entirely innocent, but the most significant point bears underscoring. While the kind of thinking one does in writing is both familiar and transparent (it’s right there on the page – logical, linear), the kind of thought that makes a painting is (maddeningly, mercurially, brilliantly—whatever your point of view) hidden behind the paint. And that which is hidden is easily mistaken for that which isn’t there. In spite of ourselves, we are still very much mired in a logocentric bias – one to which, in our striving for greater cultural agency, we visual artists are in danger of capitulating.

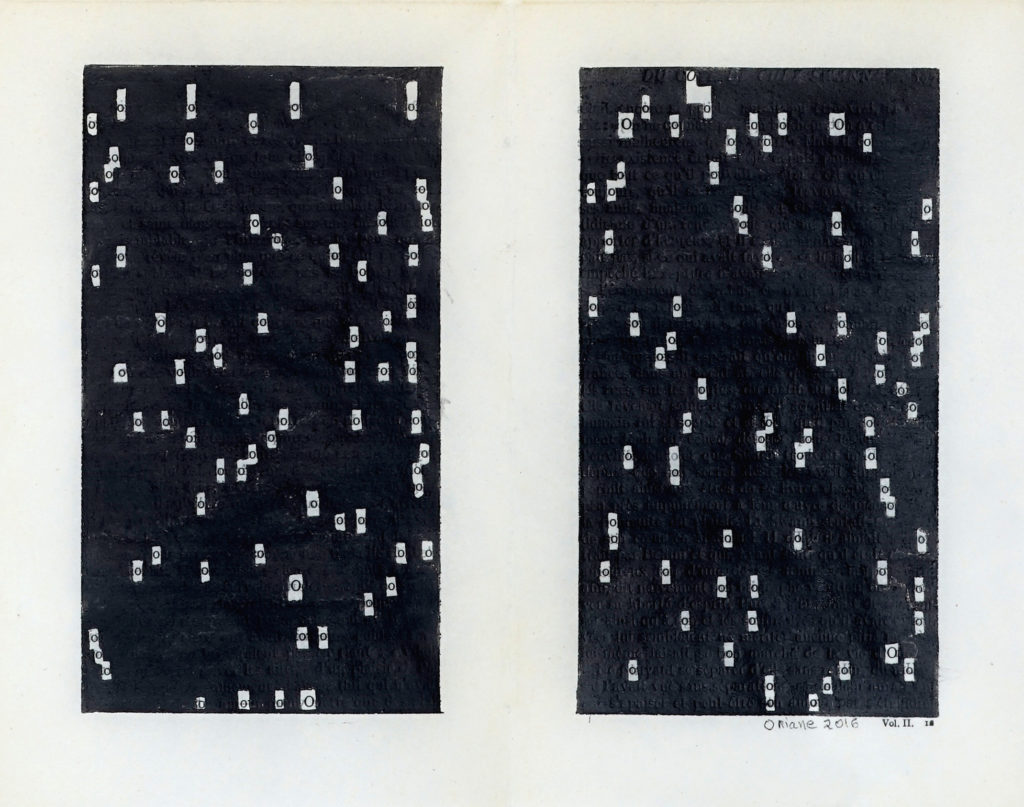

Oriane Stender, The Story of O (detail), 2016. Ink, beeswax on bookpages. 28.5" x 18.5".

What, then, is this kind of thinking that gives visual art its life, and that which is under threat of eclipse from the discursive? It’s both a kind of thinking and a kind of knowing that, while not absent from other fields, is the native home of visual art, and indeed the very soil from which it sprung. Known variously as tacit or synthetic thinking, it constitutes a way of knowing wholly distinct from other approaches to truth. While analytic thinking traffics in words, concepts, logical symbols, and numbers – all discrete “units” that combine to generate meaning – synthetic thinking is more like a field: soft in focus, indivisible, all-encompassing. Deeper than language and logic, it moves in intuitive stirrings, “hunches,” wordless insights (sudden flashes in which previously hidden connections pierce their way into consciousness). While discursive thinking registers as being very much “in the head,” synthetic thinking is felt almost somatically, as in a subtle churning that takes place in the subterranean regions of one’s being. Amorphous in nature, it thrives on ambiguity, multivalence, and complexity of meaning. In its holism, it is to analytical thinking what squinting the eyes is to ordinary seeing. It is, in essence, a kind of depth-oriented epistemology that clears the trees to give you the forest.[3]

The pressing question, of course, is what this arcane kind of cognition can possibly have to offer a culture in crisis. Does it not seem more efficient, when urgent communication is in order, to speak in the language most familiar to all? As it happens, on the deepest level, this is our most familiar language. As the cognitive linguist George Lakoff has called upon us to recognize, a full 98% of human thought is unconscious.[4] Beneath—or on the periphery of—what we think we’re thinking, unconscious mentation is happening all the time, informing the thought we think we’re consciously directing. In short, we think far more than we think, and to entrust discursive thought with sole sovereignty over our lives is to deny ourselves the vast wealth of knowledge that constitutes most of our intelligence. The power of visual art lies precisely in its direct access to this reservoir. Ask anyone who’s been profoundly moved by a work of art to articulate why, and again and again language proves inadequate to the task. Language founders not because it isn’t itself a mighty vessel, but because it simply isn’t equipped to travel in the deepest waters. The best it can do is point in their direction.

If art’s reach toward the discursive has its roots in a longing for a greater stake in the game, it may do well to ask itself this question: Why has philosophy, that most linguistically pyrotechnic of all intellectual pursuits, always been so interested in art? Why have countless gallons of scribblers’ ink been poured into its exploration, when that field has an epistemology of its own that’s no stranger to the depths? The answer is that art has something philosophy could never hope to obtain, and that is the capacity to embody meaning. The eternal envy of its wordy brethren, art reveals what philosophy can only describe, and it does so in a way of which no other human expression is capable. In exactly this sense, embodied poetic expression is the most precise language we have.

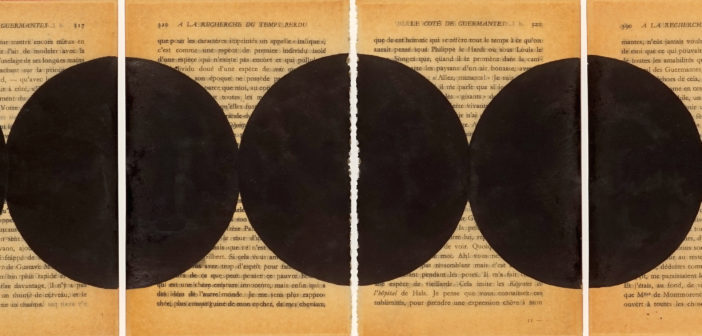

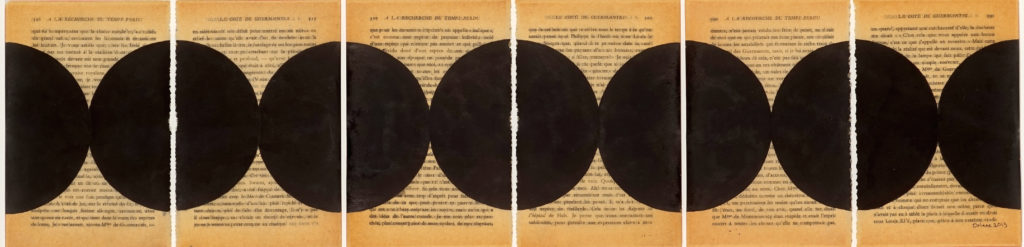

Oriane Stender, Endless Column, 2013. Ink, beeswax on bookpages. 31" x 11".

It will be argued that, be all this as it may, the eleventh hour is no time to be convincing people of art’s power. But this will be to have missed the point. For to “convince” is to traffic once again on the plane of reason, on that thin film of consciousness so oblivious to the great underneath. The only real convincing will occur—as it always has and always will—in the gut and in the bones, where the cauldron of our intelligence churns forth the conscious thought that leads to action that leads to change that leads to… otherwise. “The vessel of rigor,” writes the poet Rene Char, “flies nothing but the flag of exile.” The last thing the world needs now is another wayward vessel. May art move out into the world, but may it do so as a force in full possession of its powers—and one with the steely courage to remember what those are. Interesting times demand nothing less.

[1] It should be said that the sci-art movement is not inherently ill-conceived or doomed to failure. But in its current instantiation it’s giving us woefully little but decorative or didactic work “about” science. That said, the art-science convergence holds much potential.

[2] E.g., a typical press release might include phrases such as “an interrogation of the performativity of gender,” “an investigation of the corporeality of urban spaces,” or “an examination of the theatricality of luxury branding.” Interrogating, investigating, examining: all words whose primary function is to invoke high seriousness and authority (never mind the bloated claims that come after them).

[3] None of this is to suggest that discursive thinking has no role in the making of visual art. Conscious thought is integral to the process, but it plays a supportive, secondary role.

[4] Lakoff has suggested – very convincingly – that we cannot hope to understand our current political situation until we recognize this fact.