Drive-By Project’s Who Am I? The Sequel successfully deals with the anxiety of Trump’s America. On view through November 11, a year after the 2016 election, the thematic group exhibition provided a response to our volatile political climate. Like the previous Who Am I exhibition (presented in September 2010), the “Sequel” revolves around questions of identity and identity politics. However, the implicit question in the show’s title is more urgent and confrontational in the current social context. From varying ethnic, racial, and cultural backgrounds, each artist here sets forth a different angle from which this formative question might be asked. The show proves that there is no clear or simple answer.

Maia Chao, My Business (Cards), 2016, ink on paper, 2 x 3.5" Courtesy of Drive-By Projects.

Maia Chao’s work My Business (Cards) lays unassumingly on a white box to the left of Drive-By’s entrance. Each card contains Chao’s family tree, including each member’s ethnicity. The work circumvents the question so many non-white people are often asked, “what are you?”, offering a subtle rejoinder acknowledging systemic racism. By carrying these business cards and giving them to others, as if networking, Chao tacitly disrupts the myth of a post-racial society. The physicality of the cards refers to not only how often this question is asked, but how readily the artist feels questioned.

Like Chao’s My Business (Cards), many of the works presented here operate on subtlety. The insidiously racist and thoughtless behavior when approaching someone’s cultural identity manifests itself in many forms throughout these works. Moses Brown’s Plantation (2017) by Jay Simple, a current grad student at RISD, at first appears as a snapshot depicting a typical suburban home, complete with a woman taking her trash out. Upon closer inspection, a shadow of a man hanging from a tree branch can be spotted in the upper left hand of the photo.The title of the work specifically exposes the dark history of the house portrayed, but it also suggests the broader history of many homes in the US. Unbeknownst to many homeowners are tacts of violence that have occurred on their property. How many actually wish to know the past the walls of their house may carry?

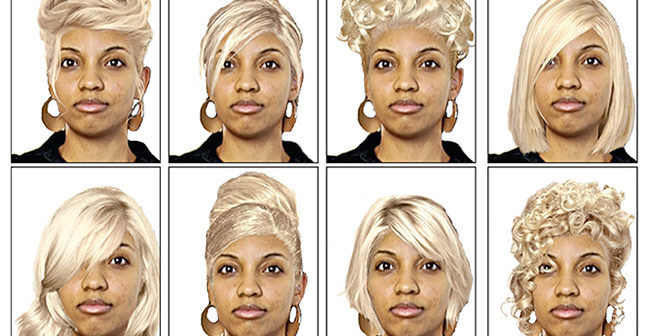

Lauren Cross, Blond(ed) Out - The Marie Makeover, 2010-2012, installed size 20 x 34", 8 framed 8 x 10" digital prints. Courtesy of Drive-By Projects.

Lauren Cross’s Blonde(d) Out also explores issues of race in the US by taking a contemporary perspective on historical issues. Cross’s oeuvre largely deals with colorism. Colorism, like other racist and imperialist theories, is the discrimination people face due to the shade of their skin tone and not race alone; rests on the idea that the lighter someone is the more valued they are. In her work, Cross digitally places a blonde hairstyle on an image of herself. The positioning of Simple’s work across from Cross’s illuminates how both artist’s work their own image into their work, but in very different ways. Simple often photoshops himself into his work, but through just his shadow, making his physical presence undetectable to the viewer, whereas Cross directly confronts the viewer with her own image. Both artists manipulate how larger societal ideas on race affect how one views themselves as people and citizens.

The show’s only paintings are from Roberta Paul’s Naomie and Naime series. Instead of integrating herself into theses paintings, Paul depicts her subjects, two sisters, focusing on their relationship. The larger painting of the two, Naomi #6, shows the two sisters facing the viewer while covering each other’s mouths. Again, an insidious ugly truth is conveyed the playful scene: the two girls silence each other, as people of color often are within larger cultural narratives. Paul’s work reminds the viewer how these silences start almost from birth and are integral to identity.

Roberta Paul, Naomi and Naime, 2017, water-based paint on canvas, 60 x 36". Courtesy of Drive-By Projects.

The show’s final work differs in its medium and content. Youngsuk Suh’s video A Day in a Life (2011-2015), made in collaboration with his wife, the poet Katie Peterson, documents Suh as he performs daily tasks on his family’s farm in California. The video answers the question “Who Am I?” in a much different nature than the rest of the show. Suh encounters some donkeys in the video, and they are more than eager to be pet and accompany Suh. The artist’s role and engagement with the landscape places him as part of the natural order, and results in a very different message than that of the works dealing with issues of race and identity. Suh can affect change in the natural landscape in real time.

A year after Trump’s election, all Americans must reassert and redefine who they are in the face of this current political climate. Though Who Am I? The Sequel was a small show, it tackles big ideas with grace and clarity. Using the personal to understand the universal, this exhibition explored politics through private perspectives.

Youngsuk Suh, A Day in the Life, 2011-2015, video still. Courtesy of Drive-By Projects.