Corridors can be odd spaces in museums, heavily trafficked but not always experienced. Art mounted in these passages can feel like an afterthought. This was not the case with Caleb Cole’s Forget Me Not, recently on view at the Newport Art Museum. Occupying the hallway of the museum’s Griswold House, Cole’s work on gender, embodiment and, indeed, the idea of ‘passing’ as male, was especially fitting in this transitory space.

The show, which ran from late May through July 30, concerned the “joy in queerness, transness, and femininity,” often manifesting with both jubilation and unease in male bodies. A self-described queer offering like this wasn’t what one might expect of Newport, or of NAM. Last fall, however, regime changes at the museum included a new senior curator, Francine Weiss, who previously exhibited Cole’s Other People’s Clothes at Boston University’s Photographic Resource Center.

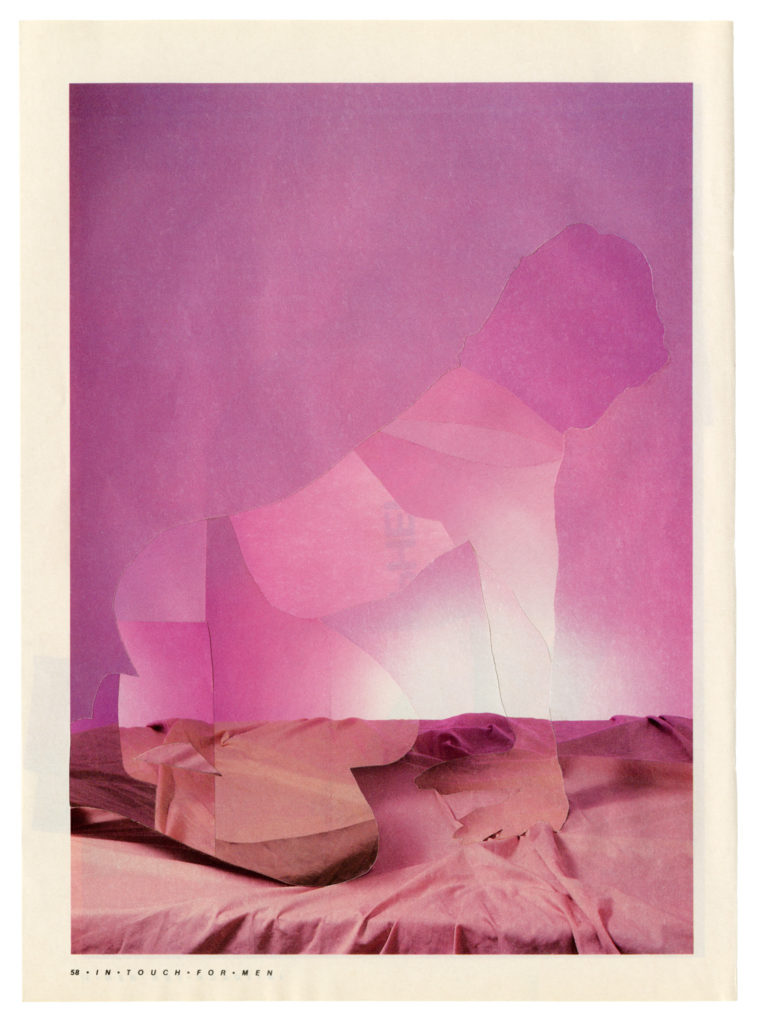

Caleb Cole, Trace (pink sheets), 2017, From the series “Traces”, Archival Pigment Print from hand-assembled collage of 1980s-1990s gay men’s magazines, Courtesy of the Artist and Gallery Kayafas, Boston, MA.

As a photo historian, Weiss was stunned by Cole’s new work, which often uses vintage photographs and ephemera, especially from the earlier half of the 20th century. Forget Me Not consisted of selections from Cole’s recent series Traces, To Be Seen, Histories and Blue Boys, all of which employ an almost archaeological approach, coaxing new (or complicating existing) emotions from the past through ornamentation with vintage postcards, jewelry or dried flowers.

For Traces, Cole cut models out of gay men’s magazines from the 1980s and 1990s, reducing their physiques to outlines and textures. These figures immediately grabbed attention with heightened saturation, subtle angles, and their disembodied sex appeal. Consider the arched back in Trace (pink sheets) (2017): sumptuous, boyish, lit by an aura of warm magenta.

Cole notes that his source materials were produced during the AIDS epidemic, thereby imbuing the salacious with the tragic. The images become a pornographic lament, their inherent lewdness alchemized into something intangible, possibly lost. One is reminded of Nan Goldin’s photos of gay lovers in the 1980s—many of whom are now dead, but immortalized, in Emily Apter’s words, as “bony bodies propped up against each other, holding onto each other for dear life…clinging and embracing in advance of the death-drive.”

Still, confining Cole’s phantasms to elegy would deprive them of their slipperiness and sinuosity. They also invoke the body’s transformative shapelessness, the palpable presence of gay desire, and the simultaneous brutality and gentleness of their mutilative process.

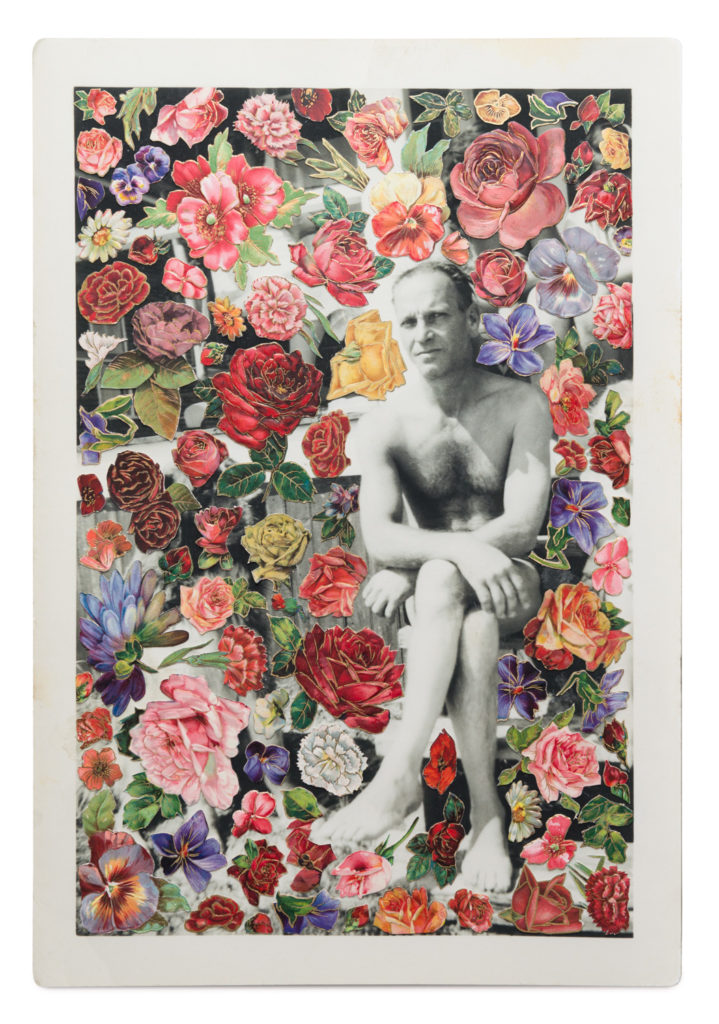

Caleb Cole, The Language of Flowers, 2017, From the series “To Be Seen”, Collage of early 1900s postcards on Archival Pigment Print from vintage photograph, Courtesy of the Artist and Gallery Kayafas, Boston, MA.

Traces warps in and out of the dichotomy of visible/invisible. To Be Seen and Histories perform something similar, by amplifying the unseen femininity of men. Here Cole adorns vintage photos of men with flowers, purses, twisting branches of gold. There’s a talismanic feel to a few of these objects, like I Say a Little Prayer (2014), a dangling chain of roses and liquid gilding. Others are full of longing, or perhaps saudade: To My Rosebud (2014) features tiny flowers painstakingly crafted from soldiers’ wartime letters, the titular phrase written beneath a photo in delicate script.

Not all the participants look willing—the cross-legged man in The Language of Flowers (2017) seems oblivious to the lush blooms around him, unwilling to indulge, overpowered by their zealous colors. This tension hints at the fear of emasculation, the loss of maleness—a grave injury in a patriarchal culture that enforces a hard duality of masculine/feminine.

As Julia Serano explains, “Much of the sexism faced by women today targets their femininity (or assumed femininity) rather than their femaleness.” She asks that “we forcefully challenge the negative assumptions that constantly plague feminine traits and the people who express them.”

Citing Serano in his statement, Cole writes that “Men’s fear of appearing feminine is in part a fear of appearing at all, of being seen, looked at and objectified in the way that women are.” And yet Cole remains affectionate toward the men he reimagines, not seeming to objectify or exploit them but rather bring out their full humanness.

Most subtly, Cole accomplishes this through color, particularly when he uses monochromatic photos, which evince the lifelessness of oppressive masculinities. Color rejuvenates and intensifies the subjects in Cole’s appropriated photos, as in Show Me a Pansy (2016), where faintly blushing cheeks seem to announce a man’s quiet discovery.

Cole’s celebratory palette could almost echo Luce Irigaray’s poetic notion of color in An Ethics of Sexual Difference:

Color resuscitates in me all of that prior life, the preconceptual, preobjective, presubjective, this ground of the visible where seeing and seen are not yet distinguished, where they reflect each other without any position having been established between them…[Color,] far from being able to yield to my decisions, obliges me to see.

Cole evokes this idea of color in Fall (2017). A young man in a photo medallion appears slightly cocky: one eye raised, lips slightly open, trying to look tough but almost surprised. Beneath him gushes a trail of paper flowers cut from old postcards. It looks as if he might fall into the ecstasy below, embracing the feminine, the beautiful, the rush of the Other. He looks dazzled, dazed. These flowers could be growing within him: intense, passionate color, burning from the inside-out, extinguishing the cool veneer of machismo.

The phenomenological space where “seeing and seen are not yet distinguished” is the space of Forget Me Not. The viewer feels their way through these images, as do their subjects: the ghosts of Traces fumble toward tangibility. The man in Helplessly and Forever (2017) looks strong but plaintive, his feeling contained but only barely. In this liminal place, Cole’s characters feel safe enough to whisper, asking to be seen and remembered. The importance of this plea is not in its content, but its volume, its almost begrudging delivery. It is a desire spoken so softly as to be breakable.

- Caleb Cole, Fall, 2017, From the series “To Be Seen”, Antique celluloid photo medallion and early 1900s postcards, Lent by Paula Tognarelli.

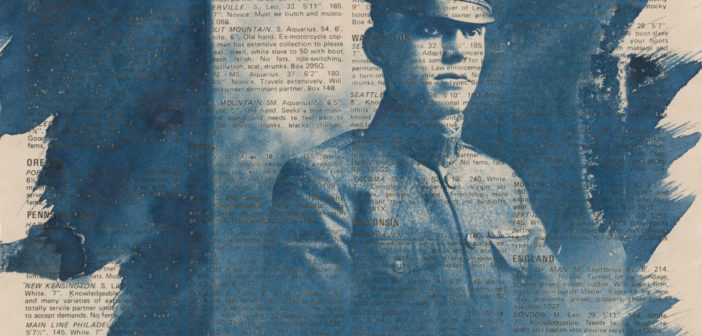

- Caleb Cole, Blue Boy #2 (Adaptable, sincere), 2014, from the series “Blue Boys,” 2014, Cyanotype on vintage magazine page, unique, one-of-a-kind collected glass negatives, printed as cyanotype on classified pages from 1970s Drummer Magazines, 13 5/8 x 11 1/8 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Gallery Kayafas, Boston, MA.