Men are a burden. This matter-of-fact sentiment prefaced the call for submissions Reflections on the Burden of Men, edited by Laura Beth Reese and Madeline Zappala. For a liberal feminist (like me), it was a fun sentence to say out loud, but the sweeping, binary language gave the impression that this lit mag would be a platform to talk about men without necessarily talking to them. I expected to find mostly angry and unapologetic essays, emotional personal stories, and darkly comic images shared primarily by and for women like me, so I was somewhat surprised when in and among the powerful and at times painfully relatable female voices, a nuanced engagement with male experiences emerged. Rather than boxing them in, the magazine effectively complicates ideas about “men.” It’s discussion of the incongruities of patriarchy and maleness, gender and masculinity, shows an explicit interest in the individuals embodying this dissonance as well as those affected in its wake. By confounding and relating these perspectives, ROTBOM carves out a meaningful place for male voices within a feminist project.

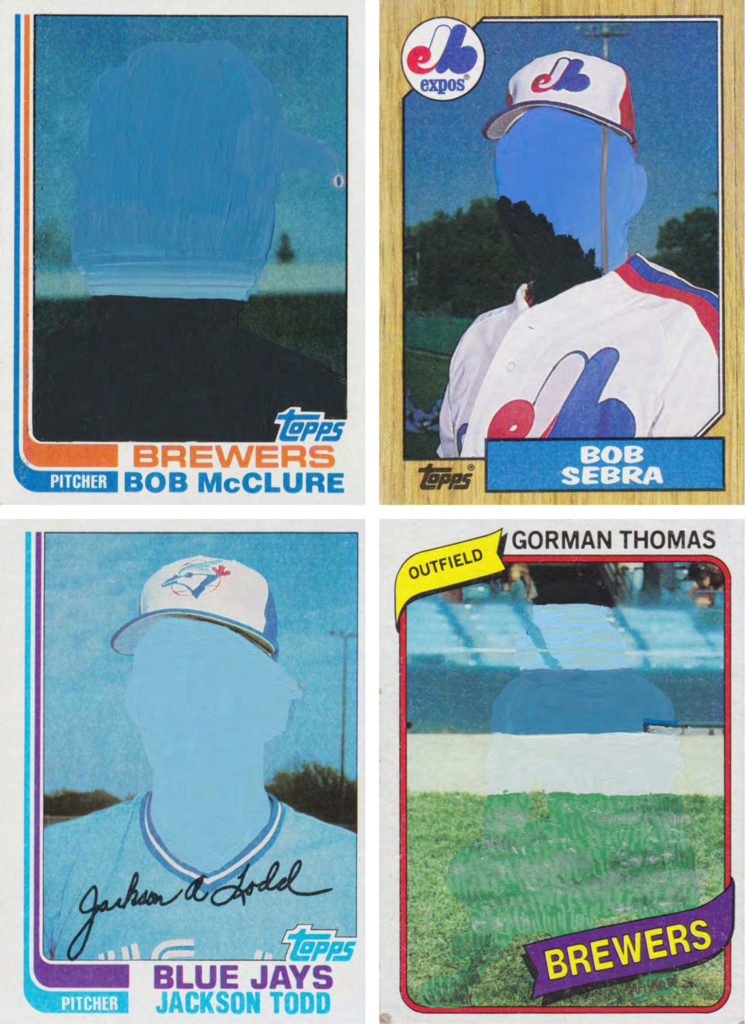

This was, of course, by design. The accommodations made in order to consider male perspectives are notable throughout the magazine. The cover, for instance, displays the acronym “ROTBOM” rather than the full title in a clear attempt not to alienate potential male readers. Similarly, the magazine’s opening group of works, which set the tone for the remainder, include Coorain Devin’s titillating images of male dolls being consumed by glittery goop, ghostfaced baseball cards painted by Samara Pearlstein, and Michael Gaughran’s essay about adolescent self-discovery in the golden age of reality TV. Shown consecutively, these pieces not only invite readers to consider men and boys coping with toxic masculinity, but also illustrate an effort by the editors to make space for, even prioritize, reflections on patriarchy’s impact on men.

Samara Pearlstein. Courtesy of the artist.

But why give men another platform? It’s possible that Reese and Zappala were influenced by criticism they received when the call first went out. In their editor’s note, they address the familiar predicament of “both being too feminist and not feminist enough,” and acknowledge the project as an exercise in “confronting our own blind spots and challenging our own thinking, communities, and privileges.” But they also lay plain their intention “to help clear a path for the voices of those who are often silenced.” So how does this confluence of seemingly male-centric works give a voice to those who are often silenced? Are the editors overcorrecting so as not to appear exclusionary?

In reflecting on the burden of men, Reese and Zappala selected works that confront experiences specific to men and transcend gestures of inclusivity. Particularly moving is Chris Maliga’s deeply personal and revelatory photo essay recounting his struggle towards manhood as an uncomfortable and asexual male in an all too familiar “authoritarian and anti-intellectual” household. The introspective coming of age story is presented alongside nude portraits of a faceless man enveloped by the forest, and culminates in a rallying call for men to take action. And yet, even as Maliga lists his strategies for managing male privilege and implores other men to do the same, there is a tension between this proposed path towards a better future and the palpable feeling of vulnerability and helplessness embodied by the man in his photographs. Ironically, his plan to move forward and alleviate the burden of patriarchy reads at times as a command for men to ‘man up’, and yet his photos seem to strip that agency away from his male subject.

This idea that men are the problem and maybe also the solution (but probably not) is echoed in the final photo essay by Matt Williams, wherein he recalls the complex questions he grapples with as a father of boys in the world today. Not necessarily antagonistic, but a bit defensive, the essay says what surely many readers are thinking: “Men place burden. Men carry burden too.” Williams describes the impulse “to throw my hands up and say, ‘Men are bad. I’m sorry I’m a man’ and slink away,” but acknowledges that this is not the way forward, not a lesson he would teach his sons. Prefacing the final three images of the magazine, which feature Williams’s father and two sons, he announces the bleak forecast: “the answers are elusive, the work is tiring, but the goal remains,” at once embodying the tireless efforts, hard fought battles, and slow progression of intersectional feminist agendas while simultaneously giving up, suggesting that even with his privileges he is powerless against the machine.

While works like Williams’ seem to let men off the hook in one way or another, several other pieces pull no punches. Digital environments created by artist Gabbah Baya feature screencaps of the horrendous, and not at all surprising, things that men have said to her online. Similarly, an anonymous account of the tech industry’s misogynistic culture was particularly biting. But these infuriating pieces focusing on men at their ugliest are the exceptions rather than the rule in this case.

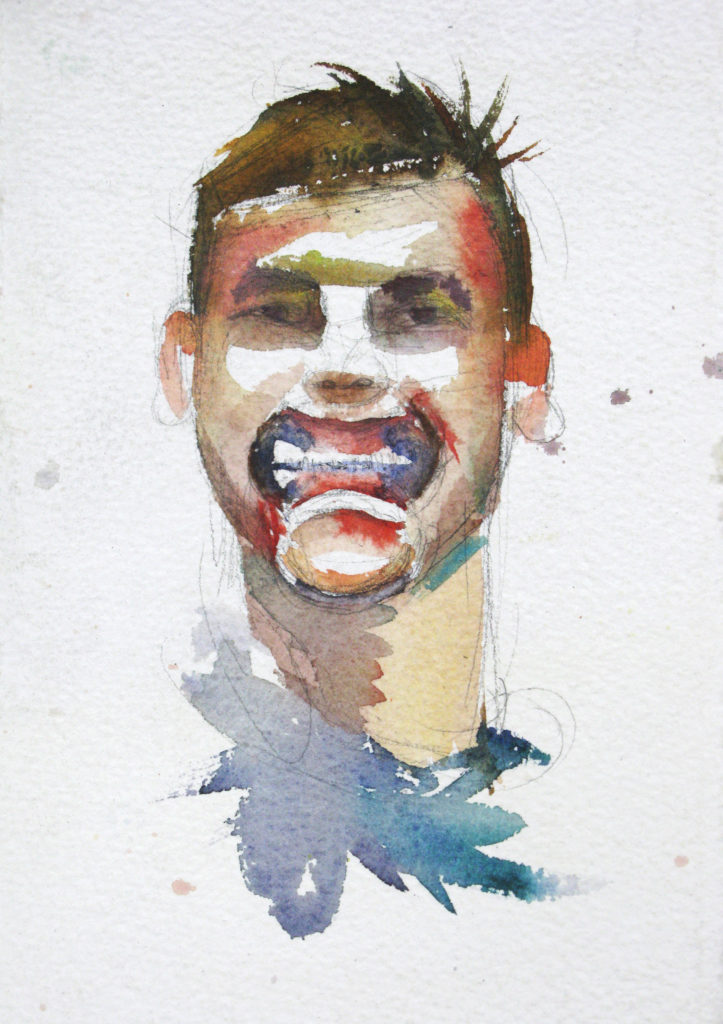

Most of the works take a more holistic and overarching examination of patriarchal hegemony. For instance, in White Youth, Molly Segal uses ugliness and aggression as an entry point for exploring the privilege of presumed innocence and the danger of presumed guilt. Her loose watercolor portraits depict young white men and boys with teeth bared by a mouthpiece from a board game. Though the images are disturbing, Segal’s subjects fail to read as monsters. They are playing a game, goofing around, and the jarring effects of their grimace are just for fun. Readers are invited to assess and likely dismiss the threat posed by these adolescents at play, and yet, the pieces serve as a subtle reminder that structural violence against people of color as well as women, queer, and trans people robs most others of that same privilege.

Molly Segal, White Youth. Courtesy of the artist.

But perhaps Marissa Lorusso gets to the heart of the project when she asks: “What can I understand without men? Can I understand sex? Can I understand power? Can I understand myself?” Reese and Zappala seem to reply that, maybe we can understand some things without men, but we understand more with them. Rather than demonizing or vindicating men, the magazine seems to call for a more united front. It highlights the struggles and pressures that operate between and beyond ideas of gender and drives home the point that the burden of toxic masculinity is shared by all of us, and we must bear it and work to alleviate it together.