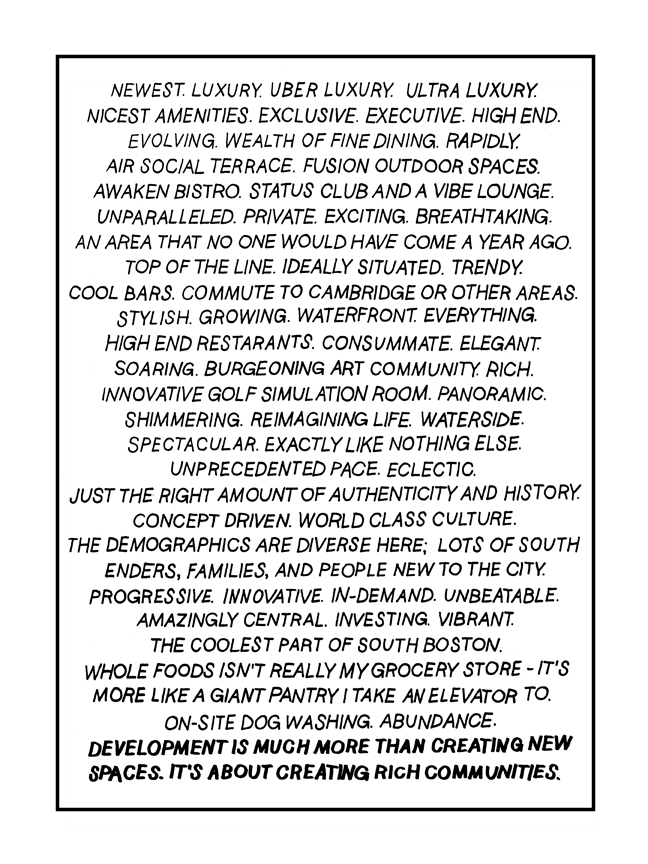

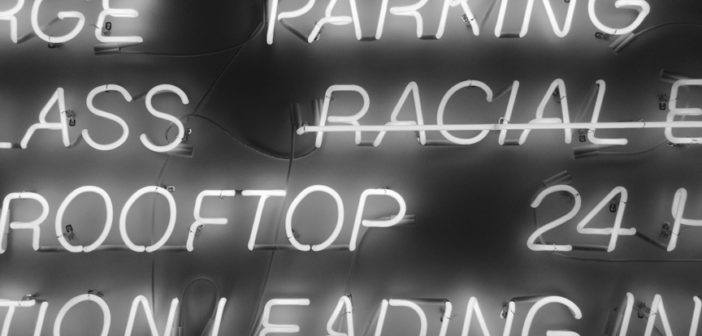

Pat Falco’s latest project, a retail intervention called “Luxury Waters” at Open Gallery in Boston is a faux marketing and sales office for an imaginary 62-story luxury development in Fort Point Channel. The building, as conceived by the artist, is a version of a glass-encased triple-decker, a building style familiar to many Boston neighborhoods. While parodying the luxury real estate market, the project is a pointed critique of a housing market that is excluding more and more people, destabilizing neighborhoods, and changed the texture and feel of a city he grew up in. The exhibition opens on September 29th and runs through October 27th. We spoke recently in Boston.

Robert Moeller: Over time your work has expressed an exasperated, almost elegiac quality. Sometimes it was funny but never really meant to be funny. It also struck me as internalized and personal. This new work is more strident and politicized, more public, if that's a good way of describing it. What is the impetus for the change? Is it environmental, in the sense that you are taking in all the changes in Boston and reacting to them or is something else at work here?

Pat Falco: That's a good question, it's both, It's definitely an environmental reaction, from the development of my own neighborhood to cities in general, I think that's unavoidable. But it actually feels like the most personal work I've made, reacting to development and gentrification has made me consider my own family's lineage here and my own place in Boston. What spaces did we occupy and what did those become? I think growing up here, everything is always referred to as what it used to be... so you kind of learn that change is natural in a funny way, and you also probably have about 5 different names for every one thing. But that also feels like a political reaction, refusing to acknowledge the thing that replaced what you needed or used. I like that moxie, and that approach to replacement.

RM: When you say that refusing to acknowledge that thing that replaced what you needed or used, what does that mean? How do we acknowledge the physical spaces we inhabit? Is it a more visceral reaction to a changing landscape, a more internalized discord with our surroundings? Also, what role do people play in how you perceive this sort of accelerated change we are witnessing?

RM: When you say that refusing to acknowledge that thing that replaced what you needed or used, what does that mean? How do we acknowledge the physical spaces we inhabit? Is it a more visceral reaction to a changing landscape, a more internalized discord with our surroundings? Also, what role do people play in how you perceive this sort of accelerated change we are witnessing?

PF: Maybe I'm projecting. I just think referring to Millennium Tower as the Filenes Building or the Improv Asylum as the European (a North End restaurant) is not letting erasure rewrite personal histories. I'm sure it's different for everyone. People play a big part in this perception, Boston has long been a racially and economically segregated city and you can tell when people are out of place. It's a new sort of colonialism.

RM: Was there a moment for you when this sense of change became overwhelming apparent? I mean, the entire city is a construction zone now, whether commercial or residential. Pick a neighborhood and it is being transformed: sterile little boxes to work in or live in, with little regard for the (former) character of the neighborhood. Is that part of it?

PF: Hmm… Yeah, I don't know. The entire city is a construction zone now, but I also grew up during the Big Dig. I think it felt like even more a construction zone then. Maybe because I was a kid it seemed larger, and the North End is a neighborhood I identify with that was directly affected by it. The removal of the elevated expressway and its replacement with a beautiful park lead to a change in who gets to enjoy the park, many family-owned Italian bakeries, restaurants, and businesses that lined the grimy highway bottom are now luxury condos, juice bars, banks, and chains. Why couldn't the people who made the neighborhood good, enjoy it when it got really good? One of the best things this research has led me across, was a quote from my uncle, Charlie Falco—he was the mayor of little City Hall in the North End during the 70s, and in regard to fighting gentrification he remarked "We made the neighborhood too good for our own good." I like the irony of that, and trying to reconsider what to do about it. Gentrification is like climate change, you can't stop it—but how can you best be prepared to survive it?

RM: You have included work by Tory Bullock, whose videos on affordable housing have received a lot of attention. Tell me about Bullock and why his work is important?

PF: He's great. I've followed and respected his work for a while, and was excited to be able to work with him on this project. He has a great ability to engage and educate, and I think his perspective and voice on this is really important. It's impossible to talk about gentrification and not talk about race, especially in Boston. I didn't want this show to be limited to one white guy's perspective, or a couple neighborhoods. This is affecting everyone in very different ways; I was hoping to provide a place to expand on those conversations. We want to host "community meetings" centered on these topics, as well as trying to plan some stuff with a Chinatown neighborhood group.

RM: I've heard the term "poor door development" in relation to housing issues. Can you explain what it means?

RM: I've heard the term "poor door development" in relation to housing issues. Can you explain what it means?

PF: It's basically separate entrances for separate people. It's fortunately not as prevalent in Boston as in some other cities, but it does still exist. Mixed income buildings will have separate doors, one for market rate, and one for the affordable housing units. The "poor door" is usually on the side, around back, and a little more discreet. It's Jim Crow-esque and segregates "mixed" housing.

RM: Your project, which envisions a 62 story, glass encased triple-decker is a luxury development parody. Knowing just how cold-hearted real estate developers can be, did this work afford you the opportunity to include a set-aside for affordable housing? How does the city actually deal with these projects? Is it on a case-by-case basis or is there some over-arching policy in place?

PF: Yes, definitely. In this instance, the affordable units will be underwater. This is because of just how vulnerable this area will be to climate change (as sea level rises, we can add more affordable units) and to amplify how useless "affordable" housing is in luxury units, when there is nothing affordable in the neighborhood. If you don't have access to affordable food, groceries, clothes, and entertainment... what is there for you? The city has various ways they deal with this, generally 13% of new buildings with more than 9 units has to be designated "affordable". In addition to that being a low number, this is problematic because affordable is based on the Area Median Income (AMI, $98,500)—and these units are usually for about 70-120% of the AMI. This area includes 114 towns, two of which are in New Hampshire, and two of which are Lexington and Wellesley—which have two of the highest median incomes in the country. The Median Income for the City of Boston, is about half that ($53,482), and half of residents in Boston make less than $35,000 annually. These "affordable" units are pushing people out just as much as the market rate units. On top of building housing that is systematically not for Bostonians, through the use of EB-5, they can take advantage of some of Boston's most vulnerable neighborhoods, to benefit foreign investors.

RM: Which brings us to another potentially interesting question, given the predicted effects of climate change, specifically the sea level rising, warmer ocean temperatures and the threat of catastrophic storms hitting Boston, what are developers and city planners thinking? I realize it is a bit of a gold rush but isn't it incredibly shortsighted? And frankly, they aren't alone. Isn't the ICA expanding into another water front property in East Boston?

(Note: You can check just how far above sea level your home is here)

PF: Yeah it seems really short sighted, I'm sure the developers will be long out of the picture, and maybe the city will be able to rely on all the money they're making and having a more affluent population to help fix it. Maybe GE can put a bunch of helipads in and the whole city can just get helicopters. It seems like their approach will be more reactive instead of preventative… got to make sure they get that money first. Yeah, the ICA is opening a location in East Boston, and if they Mayor get's his Amazon dream it will be really sad to see what happens in East Boston.

RM: And finally, I think. We are beginning to see galleries closing, in many cases because of skyrocketing rent increases. Some of these galleries, in the South End, specifically, were some of the first new businesses in neighborhoods that are now seeing massive redevelopment, especially on the residential side of things. With so many other socioeconomic problems facing city government, should artists and arts professionals have a say in redevelopment issues that relate to their ability to work and live in the city?

PF: Yeah I mean, I think they should have a say, but I don't think it's a more important voice than anyone else’s. Artists share a responsibility in redevelopment that we need to be accountable for. When you move into a neighborhood how do you choose to interact with it? Are you engaging with longstanding community business, are you creating spaces and events that are accessible to the community that existed before you showed up? It's not just galleries that have had to leave the South End, I can think of a handful of restaurants, cafes, and shops that have had to leave as well. They all deserve a say. I think a problem too is we hear a lot of the focus on affordable housing, but there doesn't seem to be much conversation about affordable retail and commercial space. You don't have access to starting or maintaining a business without a large chain or serious investments behind you, which boxes out people from maintaining or opening spaces in their own neighborhoods.

For more information on development projects taking place in Boston, you can go to the City of Boston's Department of Economic Development's Boston Residents Jobs Policy office which monitors the compliance of developers and contractors. For information related to the wealth gap in Boston that Pat mentioned, you can find this report by Ana Patricia Muñoz for the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

1 Comment

Thoughtful work and commentary.