When Matter & Light director, Ian Corbin, describes his life’s origin, it is almost unbelievable. This, in part, is due to his aesthetic: he’s on the couch in the back of the gallery finishing up an email on his MacBook in a blue button down, dark jeans, and polished leather shoes. His longish hair is coiffed back and a watch keeps time on his wrist. “My parents were in a reggae band when I was born and they were hippies. Music was very important to them,” Corbin says. He goes on to explain how that all changed when he was two years old: his parents abandoned their freewheeling existence after a conversion experience and committed themselves to Pentecostal Christianity. From that point forward, intransigent and ecstatic faith dominated Corbin’s upbringing. He describes his childhood home as “militantly conservative” though believes there was some good in that way of living.

In his early twenties Corbin began to interrogate the dogmas and doctrine which had posed as instruction manuals for his life. “My faith started to wobble,” says Corbin. “Without ever consciously deciding, I turned to philosophy and to art”. Unbound from religion’s claim to spiritual answers, he changed his major to philosophy, packed his bags, and went abroad to study. It was in the midst of his year abroad, visiting the major European cities and museums, that Corbin realized he was shouldering a life of deep questioning and gravitating towards others who were trying to cut to the core of the human condition.

Now thirty-six, Corbin teaches philosophy at Northeastern University and heads Matter & Light, an emerging fine arts gallery in the SoWa Art and Design district. The space, which opened in April of 2016, is tucked into the lower level of a two-story complex where upstairs neighbors include the likes of Samsøñ and Gallery Kayafas, both successful establishments in their own right. One would think that keeping a low profile while shoulder-to-shoulder with your peers would prove difficult, yet Corbin has managed to fly below the radar while slowly accruing an impressive and impassioned collection.

“Naked”, Luca De Gaetano, 72” x 90”, oil on canvas, 2017. Courtesy of Matter & Light.

Corbin’s foray into the art world has coupled with a voracious desire to connect with artists who share his dedication to the human experience. He chose the name Matter & Light to encapsulate what he believes to be an elemental discrepancy of being human: that we have to deal with our material existence in matter even as we aspire to greater spiritual heights or think about what happens to our souls after our bodies cease to work and we die. Corbin says he got the idea from the chorus of Leonard Cohen’s song, “The Window”, which distills our earthly condition down to a “tangle of matter and ghost”. This problem, Corbin believes, drives the work of each of the artists with whom he works.

Matter & Light now represents eight artists, double last year’s number. Within the roster, art world heavyweights garner as much attention and respect as greenhorns. Sam Messer and John Walker, whose collective works have graced some of the world’s most eminent museums and collections, show alongside rising talents like Aristotle Forrester and Iranian artist, Bahar Ejtemaei. Aesthetically, Corbin’s criterion for selecting a particular work is double-sided, a balance of kinetic and potential energy: “It needs to have that initial gut punch, but it also needs to stand up to some sustained scrutiny”. His other requirement is honesty: a work that does not compromise, skim over, or settle for an easy fix. When I press Corbin to summarize his taste, he tells me it’s tied up in a question: “Is the art being honest about what it’s like to be human or is it giving us cheap answers?”

“Not Your Family Portrait”, Marilyn Levin, 40” x 30”, oil on canvas, 2015. Courtesy of Matter & Light.

The ten works hanging in Matter & Light’s front room buzz with energy. The majority are paintings with the exception of one Messer print. Corbin’s title for the exhibition, “Summer Group Show 2017”, irked me at first: it seemed flippantly utilitarian, like turning in an art history essay entitled “Art History Essay”. However as I spent more time with the work, I saw less of a need for a unifying theme. The remarkably unremarkable title felt liberating, allowing the works to chatter and babble amongst themselves rather than be pigeonholed into a particular dialogue. Corbin’s preference for unbridled color charges through every piece, proving that some aspects of his upbringing are inescapable. “Euphoria, losing yourself, was a big part of our religious experience and also going to punk rock shows,” Corbin says as we walk around the gallery. “I like being overwhelmed. I like aggressive aesthetics. I like things that jump off the canvas and kind of wrap around you.”

The most extravagant display comes through in the largest works by Italian architect-cum-painter, Luca De Gaetano. “Naked”, which appears to be a sexualized rendition of an expulsion from the Garden painting, vibrates fervently on the right hand wall. The supine Adam and Eve figures stare upward in a trance-like gaze as an entropic and watery spectacle materializes around them. A green wash becomes a landscape laden with spectral animals (Seussian elephants, a shark, a stray ostrich), human faces, and other surprising characters. Exploring the details of De Gaetano’s work is not unlike an excursion through Hieronymus Bosch’s notorious “Garden of Earthly Delights”. His other large canvas, “Cythera” is equally loaded and passionate. It acts as an ode to Jean-Antoine Watteau and his Rococo masterpiece “The Embarkation of Cythera”, a lush and lustful depiction of the mythic island where the goddess Venus is said to have been born.

Where De Gaetano’s work explodes with vibrancy, Marilyn Levin smolders. Two paintings from her “Not Your Family Portrait” series enter a realm of the almost-namable. In “Not Your Family Portrait #5”, a bulbous head seems extraterrestrial against cosmic darkness. The sticky, atmospheric blue gives way to septic yellow and textured wrinkles that recall aging skin and bring us back to the materiality of the body and its bizarre decay. On the same wall, Bahar Ejtemaei’s, “The Burned Theater Series No. 1” does not feature the figure but alludes to its absence. Scrappy line work acts as architecture for the dilapidated scene. As the painting wavers in and out of abstraction, one makes out evidence of human life: a tea kettle, some hanging cloth, a burst of fiery orange that perhaps stands in for an open fire for cooking. Somehow the scene is hopeful. Perhaps it come from the sensation of light Ejtemaei achieves at the center, a soft ochre glowing through charred umber and smoky green.

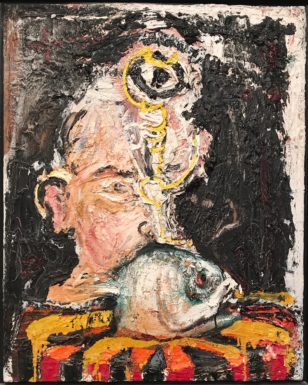

“Portrait with Fish”, Sam Messer, 24” X 20”, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Matter & Light.

For a gallery that recently broke one year old, Corbin is aware that he has lofty goals. Perhaps it’s paradoxical, but ultimately he aspires to maintain the mosh-delighting posture of a punk rocker while operating within the art world’s rigid system and traditional values. Already he has shown an ability to foster a group of artists from different cultural backgrounds, ages, and gender identities who offer a diverse and cosmopolitan perspective. Despite the range of experience, the artists and curator continue to gnaw on the same existential questions. As Corbin puts it, he is captivated by his artists because they are not afraid to address the uglier, disturbing parts of our existence: “It’s precisely because they want to show that right in the face of that fragmentation and brokenness the world is actually still beautiful.”

1 Comment

Pingback: The philosophy behind M&L, in Big Red & Shiny - matterlightfineart.com