Sun Splashed: Nari Ward, the artist’s largest survey to date, is now on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. Organized by Ruth Erickson, Mannion Family Curator, with Jessica Hong, Curatorial Associate, this show couldn’t have come at a more appropriate socio-political time while our country is being separated. The monumental works presented here investigate social justice, immigration, memory, oppression, and power while engaging in local sites, history, and many different communities. The exhibition, comprised of works spanning across 20 years, has traveled the last three years, first at the Perez Art Museum, then at the Barnes Foundation, and finally at the ICA Boston.

Installation view[s], Nari Ward: Sun Splashed, The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2017. Photo[s]by Charles Mayer Photography. © 2017 Nari Ward

It’s an honor to share my conversations with artists I respect and admire. Many of these artists’ ideas drive my own critical writing, inspire my art practice, thinking, and work ethic. Earlier this April, I was part of the installation team at the ICA and worked closely with the spectacular and monumental work of Ward and the artist himself. After taking in the work and the experience of being with and inside the work at the ICA, I finally got to speak in depth to Ward about memory, labor, immigration, and citizenship.

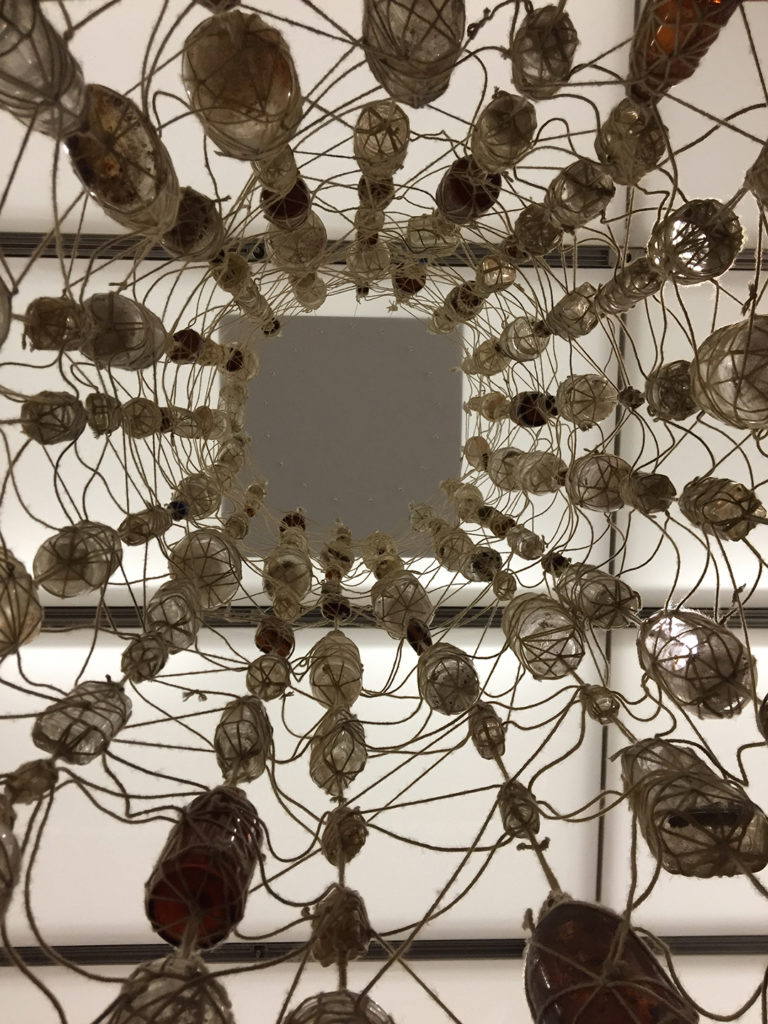

It was a great experience to be able to handle Ward’s work and position myself within the sculptures and installations, almost mimicking the way Ward perhaps was looking at his work while creating it. Being in the perfect space, which regular museum goers wouldn’t be able to experience, allowed me to create my own journey in being with Ward’s work. Installing Sky Juice, (1993) for example, I was inside the umbrella holding the piece during installation; I felt inside a baptism, transported in time looking through the found photographs resting inside the melted plastic bottles, each preserving a memory in tiny coffins as water splash sounds washed over me while Jaunt (2011) played beside me. In Sky Juice, Ward used photos from a beautiful family album found in an empty lot, where someone’s apartment was vacated and it became the entire trigger for the piece. Tropical Fantasy Soda has been cooked down to the sugar crystals, concealing shoes and personal belongings, stuck within small openings of a church fence, evoking personal and universal memories.

Installation view[s], Nari Ward: Sun Splashed, The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2017. Photo[s]by Charles Mayer Photography. © 2017 Nari Ward

There were many individual moments—especially powerful ones being an artist, and thinking about aspects of Ward’s practice—during the install when I got to experience and be a part of the work. After installing Vertical Hold (1996), I laid onto the floor directly beneath the center of the piece and looked up, thinking about the history and journey of each found bottle, and wondering if Ward did the same thing. “It is inevitable that when the work leaves the studio and goes into this kind of space, whether it’s a museum or a collection, you realize it’s about you getting distance from it and see it in a way you don’t normally see it, and the bad part is that you don’t have control over it anymore,” Ward explains.

Many of the materials Ward uses in his installations are scavenged, found, reclaimed, and repurposed. For the LiquorSoul signs, Ward tells me that there are a few different versions he owns. The first abandoned Liquor sign he came upon was on 145th Street & Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd. in New York City and was for an exhibition called NeoHooDoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith which dealt with the use of spirituality and rituals in contemporary art. When Ward called the landlord to ask for the neon sign, the owner didn’t remember it was there anymore. Ward explains that once the liquor store is gone, nobody ever goes back to take the neon sign down because it costs too much, so it dies there, becoming an eyesore only until an artist like Ward finds a new home for it.

Installation view[s], Nari Ward: Sun Splashed, The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2017. Photo[s]by Charles Mayer Photography. © 2017 Nari Ward

The influence of personal memory, Jamaican and African-American culture, Voodoo traditions and ceremonial approaches appear in almost all of the works in Sun Splashed, from the texture of work to the smell of every found material. Voodoo tradition, rooted in Afro-centric approaches to material transformation, influences Ward’s practice even if it’s not formalized.

Ceremonial traditions are prevalent to his practice, and Ward finds a way to incorporate different ceremonies into the vision of the world and his experience of it. As part of site-specific work for the Anne H. Fitzpatrick Façade at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Ward created the artwork Divination X (2015) inspired by fortune-telling ritual through x-raying the configuration of the elements with the bag and clusters of cowrie shells examining the act of divination.

Installation view[s], Nari Ward: Sun Splashed, The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2017. Photo[s]by Charles Mayer Photography. © 2017 Nari Ward

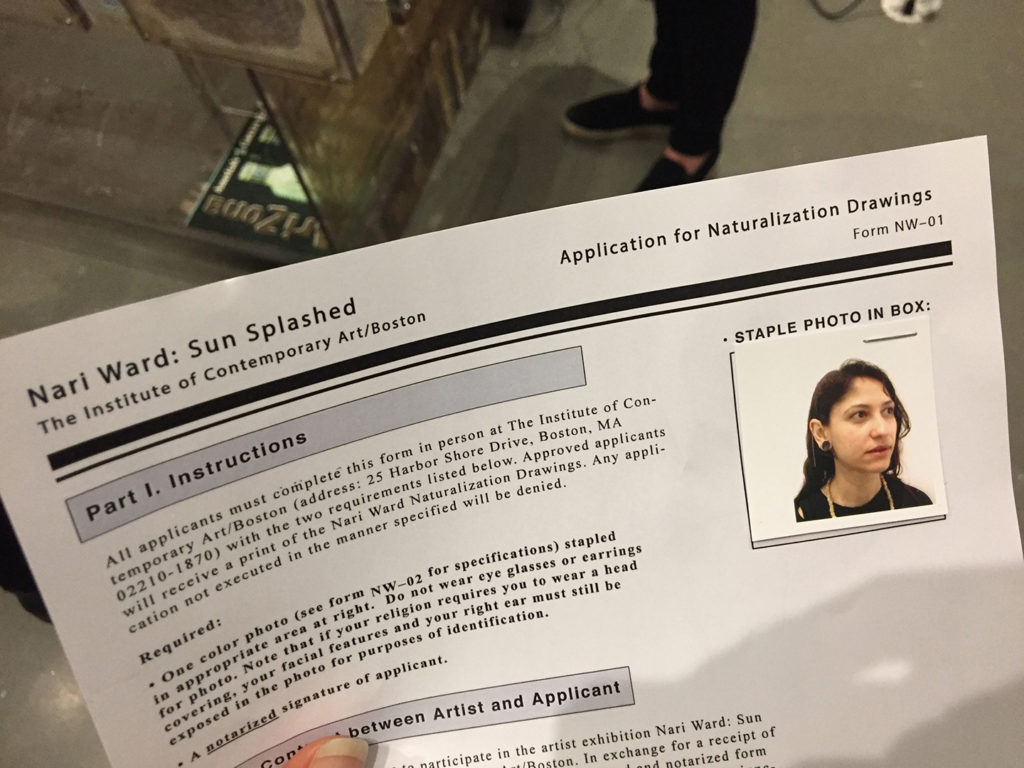

In the performative and participatory installation, Naturalization Drawing Table (2004), Ward creates a bureaucratic structure and ceremony via engaging in and applying for U.S. citizenship. The structure created out of recycled plexiglass bodega barriers is a power structure, changing the meaning from a display model to a fort-like structure encasing a set of drawings created on Immigration and/or Naturalization forms.

In this case, the guardian of this bureaucratic structure being the museum, the visitor fills out an application and await the process of getting approved. After approval, there is an exchange of application for a suite of the drawings. If the person has that art piece, it’s only valid if Ward has the visitor’s image; if that visitor tries to sell the artwork, it’s not valid if Ward doesn't have their application, a contracted gift. In terms of your demeanor, Ward says to the visual assistants, “I really want formal, business, and professional attitude when dealing with the visitors”.

Which reminds me of the time my family and I got naturalized in 2006, my mother and I cried, feeling like we had betrayed our homeland, a ceremony which still haunts me.

"I think a lot of people who go through that process, and the process of aligning yourself with one system, as an anonymous machine, and it can be dehumanizing. What’s interesting in that component of it is even when you’re faced with those indifferent systems, a sense of community starts to evolve, and I was thinking of the singular experience of dealing with that. The notion of the group started to become really relevant and important in the waiting period. As an artist I was really thinking of the journey having to deal with this process bureaucratic negotiation, and what I didn’t expect was the community of waiting, everyone being in the same space, having their own anxiety, and similar ideas of what this means to them—which was really rewarding—something that as an artist you can’t really plan,” clarifies Ward.

We The People (2011), one of the largest and more laborious works in the show, is composed of thousands of diverse shoelaces carefully guided in small holes. After hours of installing each shoelace, I started to get into the flow of the work, letting go of ego or separation and fully immersing myself in the process. Issues of labor, justice, and citizenship speak volumes here.

We the People of the United States,

in Order to form a more perfect Union,

establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility,

provide for the common defense,

promote the general Welfare, and secure

the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and

our Posterity, do ordain and establish this

Constitution for the United States of America.

This is written on the third page of my U.S. passport, above my photo and personal information, as if they were lines in a Bible; I believe them, we are safe now. Many handlers and young kids from the ICA teen group installed this work, and on the last day, I finished install by sealing each and every exposed—like a wound—recalling those words on my passport.

Installation view[s], Nari Ward: Sun Splashed, The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2017. Photo[s]by Charles Mayer Photography. © 2017 Nari Ward

Nari Ward: Sun Splashed is on view at The Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston through September 4, 2017