William Eggleston has the distinction of being among the most emulated of color photographers. Made famous by his groundbreaking and controversial solo show at MOMA in 1976, his images carry with them the confusion of being simple, formal, colorful, serene exercises; likewise, his many imitators pattern their own worlds into shapes and colors, and shush them into silence. As Jurgen Tueller, the fashion photographer, has stated: “Often there is something morbid about his images that's mysterious and compelling, and unique to him. Everyone, including me, has at one time or another wanted to do that sort of Eggleston picture, but never succeeded. It's totally about how he sees things in his mind's eye.”

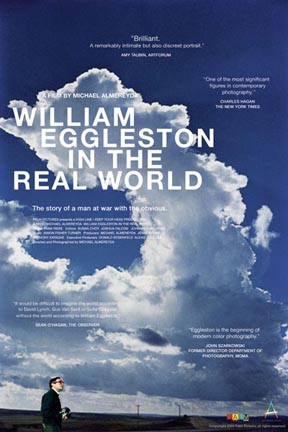

“William Eggleston in the Real World,” a new documentary by Michael Almereyda shown several times last month at the MFA, offers an intriguing insight into the mind’s eye of Eggleston, a man far more fascinating than his artwork. Call him the anti-Richard Serra, if you will.

Initially, he appears in the film, like his photographs, to be considered and banal: a dandy in three piece suits, silk scarves, and carefully combed grey hair. Eggleston is tall and lean with an old world sensibility and the soft drawl of a Southern aristocrat, having grown up on a plantation in Mississippi. He seems instantly trustworthy, all apple pie and sweater vests, cutting a Rockwellian figure like Mr. Rogers. He’s been married for forty years to “a girl from Mississippi.”

The tragedy of the first part of the film is the apparent disconnect between the remains of the old South and the sudden emergence of a more modern one. Eggleston prowls around like an old bear in a small Kentucky town with his camera and his son by his side. Later they come upon an abandoned house by the side of the highway where Eggleston photographs voraciously, a metaphor for the diminishing remains of Eggleston’s South?

Soon it’s clear that it is we who are unprepared for Eggleston. One sudden scene involves his mistress, Leigh Haslip, in an extended monologue on a couch wondering what would happen if she got cancer. She fills half the frame, a drunken odalisque, Eggleston is tiny in the far corner in a small chair, hunched over making a drawing with colored pencils. On and on she plods about her potential cancer...”my brother said he wouldn’t pay for it...and I wouldn’t want him to pay for it...what would I do?” Eggleston looks up from his scribbling and offers this sensibility, without a hint of maliciousness, “why don’t you just go into the desert and die?”

Poke around and you get these Eggleston anecdotes: the time he pulled a butter knife on a professor at the Harvard faculty club while he was teaching there, the long affair he had in the 70s with Viva from Andy Warhol’s Factory, his cameo in the movie “Great Ball of Fire” as Jerry Lee Lewis’ father, his interest in antigue guns, especially shooting them indoors in the dark, the Gatling gun he has pointed at his front door in his Memphis mansion (which can shoot 1,100 rounds a minute), the time he was stranded in a small town Mississippi motel by an enraged girlfriend with just the clothes on his back and his box of colored pencils.

In spite of his wild misadventures, Eggleston is refined and erudite in certain circles, and none of it is an act. If there is one shocking insight from the film, it is the portrait of a contemporary artist completely free from the trappings of any artistic theory or reference. In his conduct, in the revelation of the contradictions of his life and of his art, Eggleston acts instinctively. About his photographs, he says, “I've never noticed that it helps to talk about them, or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn't make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them. People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken. It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they're right there, whatever they are.”

As the documentary reveals Eggleston composing ridiculous electronic symphonies on his synthesizer and showing off his strange abstract pencil drawings, a unique portrait of the artist is composed. Eggleston is always producing, always responding, it just happens that he has become famous for his photographs. It must be noted that clips of his film “Stranded in Canton” were shown, an absoutely stunning series of hand held video shot in the early 1970s with a Sony Porta-Pak, among the first portable video cameras. The scenes shown are raw and intimate closeups of people in bars and in their homes, drinking and interacting with “Bill, you fucker”, mostly unaware of the camera. Decades before its time visually as well as thematically, “Stranded in Canton” is edited from hundreds of hours of footage. Eggleston never again made video work, and didn’t even bother to show anyone this footage until around the time of this documentary.

Given that the enigma of the artist’s mindset and philosophy outweighs any insight offered on his process, this documentary serves as a true portrait: a fascinating image of a person you would like to know more about. In an interview with a British newspaper, Eggleston was asked how he would like to be known. With a twinkle in his eye, Eggleston said, “as a lover.”

Links:

William Eggleston Artistic Trust

Michael AlmereydaMuseum of Fine Arts Boston

"William Eggleston in the Real World" is currently showing at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and is co-presented by the Photographic Resource Center.

All images are courtesy of the William Eggleston Artistic Trust and Film Forward