“Braun Celebrates 50 Years of Industrial Design: 1955-2005” is currently on view at MassArt’s Bakalar Gallery. Boston is the exhibition’s only US destination; before traveling to Massachusetts, the exhibition was on view at Royal College of Art in London and Braun HQ in Kronberg, Germany. Although Braun’s roots are in pre-World War II Germany—company founder Max Braun began producing components for radio sets in Frankfurt in 1921—the show marks the fiftieth anniversary of Braun’s minimalist display at the 1955 Düsseldorf Broadcast Exhibition, where a new line of Bauhaus-inspired designs for radios were unveiled. Max Braun’s sons, Artur and Erwin, took over the company when their father died in 1951, and they were responsible for creating the look of and philosophy behind the brand we are familiar with today. Their goal was to bring “honesty and humanity” to everyday appliances like blenders and shavers, and their brand philosophy was defined by innovation, quality and design. This philosophy extended beyond the products they manufactured to a concern for their employees’ well being, which manifested itself in health food being served at the company canteen!

Artur and Erwin’s desire to create a more honest and humane company can certainly be seen as a reaction to living in Nazi Germany, which favored Romanticism over Modernism. (The company was also involved in the war effort.) The shift in Braun’s brand philosophy coincided with High Modernism in the arts—architecture, painting and sculpture, among others—that emerged from the rubble (literally) of World War II, particularly in razed Europe. It can also be said that this shift had its roots in the Bauhaus founded by Walter Gropius in 1919. Indeed, Braun’s first products in the new design—the radios displayed at the 1955 Düsseldorf Broadcast Exhibition—were designed by the Ulm Academy of Design, which saw itself as a continuation of the Bauhaus school of design.

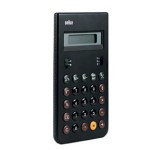

The exhibition itself, which is well designed if heavy on wall text, ranges from one of the earliest radios in the new style, the SK1 (1955), to electric kettles and toasters designed as recently as 2004. The Phonosuper SK5 (1958) was the first radio/record player to have the controls on top; the Plexiglas cover (novel at the time but now standard) earned it the nickname “Snow White’s coffin.” An ergonomic calculator from 1977 features convex buttons in an attempt to prevent user error. The exhibition also highlights a number of electric shavers, Braun’s trademark; the first, the Sixtant, was produced in 1962 and sold 10 million units in 10 years.

Now a subsidiary of Gillette, Braun remains a standard for industrial design—this exhibition explains how and why it came to be that way. Viewing the show, I had contradictory impulses: on the one hand, I felt an appreciation for the elevation of well designed ordinary objects to a space and status normally reserved for fine art; at the same time, upon recognizing the coffee mill and hand blender from my mother’s kitchen, I asked myself, “What is that doing behind glass?” For those of us who aren’t industrial designers, having grown up with Braun design and its legacy, it’s easy to take for granted how truly revolutionary the concept of good design in functional objects was (and is). Indeed, Braun was one of the first companies to consider design as an essential element of production rather than an afterthought. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was one of the first art institutions to recognize this by adding Braun designs to their permanent collection; recent exhibitions like “SAFE: Design Takes on Risk” are a reminder of their commitment to honoring innovation in the field of industrial design.

The website accompanying the exhibition includes a section titled “Bring your own Braun,” which features a gallery of Braun products members of the public have brought to the various exhibition sites. For example, a Classic Multi Mix blender owned by a Mrs. A. Sanderson of the United Kingdom features a picture of the item and the testimonial, “We have used this everyday for 35 years and can’t find anything more efficient.” There is something inherently charming in these photographs and captions that makes a visit to this portion of the website well worth it.

Links:

Massachusetts College of Art

Braun: 50 Years of Design

"Braun: 50 Years of Design" is on view until January 14th at Sandra and David Bakalar Gallery, located at 621 Huntington Avenue, Boston.

All images are courtesy of the Barun and the Massachusetts College of Art Exhibitions Department.