Since the 1990s, Beverly Semmes’s work has been at the forefront of contemporary art. Semmes’s work is situated at the nexus of American feminism, puritanism, and history of sculpture and craft. This work spans across disciplines and cultures, from photography, sculpture, video, and large-scale installation. I first met Semmes two years ago while serving as Assistant Director of Samsøñ and working on her collaborative project (with Jennifer Minniti), Body Double. The collective utilized Semmes Feminist Responsibility Project [FRP] drawings as visuals and conceptual source to establish new politics and fashion pieces in efforts to taking back the body image. In 2012 Semmes ceramic work appeared in a two-person show at the gallery [Tuesdays & Saturdays] with Nicole Cherubini, a long time friend and collaborator. In Wild Child, now on view at Samsøñ, Semmes presents work utilizing fabric as a material and metaphor from 1994 to 2017, surveying her practice.

Car Wash Collective. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes and Samson.

As you enter the space, each work invited you to investigate a certain time period in Semmes life or perhaps her many versions of the Guardian as she goes through the Penthouse and Playboy magazine pages – frantically covering them up, adopting her grandmother's personality, and protecting the image of these women.

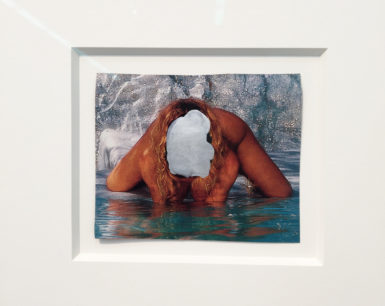

Wild Child features five dress forms and one FRP, Swim, 2016 - depicting a woman whose face is covered with a circular blob shape. The face hangs Samsøñ’s back wall, staring at the dresses as to decide which one to wear. The body position forms a pyramid shape – more vulnerable here than its resemblance in the installation shape of the piece Wild Child, where the pyramid shape appears more grounding. Is the woman in Swim the Wild child? Is her face covered as an act of protecting her image? And if so, is Semmes the Guardian, the protector, the confidant to our image as woman?

Beverly Semmes at Samson. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes and Samson.

Wild Child, 2009 is the largest piece in the exhibition is comprised of dog head printed fabric, rolls of solid colored fabric sprawling onto the floor, as if grounding the piece into firm ground. This character is the ‘Bitch’, inspired by the 90’s feminist fairy tale Sexing the Cherry by Jeanette Winterson. The open quality of the dress forms invites the viewer to investigate the works closer. There’s a scale issue and even though they call for more room, there is still a vulnerable and flexible sensibility with each piece. I imagine these pieces draping and stretching out through windows of gothic churches – covering acres of land – as Semmes sits as the gatekeeper.

Beverly Semmes, Wild Child. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes and Samson.

In previous reviews, the presence of Semmes’s monumental works with dresses or the shape of the dress have been described as demanding space, or aggressively claiming the space – most times said by male writers. Thus I wonder why it is that a woman “commanding” space is necessarily negative? Why is this understood as demanding (with its negative connotation)? Why is it that being commanding or demanding categorizes as “Bitch” ?

Beverly Semmes, Swim. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes and Samson.

There is a thematic and craft connection between the FRPs and the fabric work; an open, fast and loose state of mind. This is true in Teeth, 2017, where the work is less weighted down, has an ethereal and ghostly quality to it and seems to be dissolving – less like a body and more of a spirit. Similarly, Pebbles, 2017, seems to be taking on similar qualities of floating and looks lighter. The central silver shape in the middle of the FRP resembles the way the Pebble piece has the red circles in the chest – almost like a logo or a middle evil family crest – stamped and Semmes approved.

Beverly Semmes, Pebbles. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes and Samson.

Beverly Semmes, Teeth. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes and Samson.

While speaking with Semmes about the choice of the works selected for the exhibition, she mentioned to me she likes the exhibitions to have a wide range of works which allow the viewer to get into the tactility of the work more. The mounting of each exhibition always changes in response to the architecture of the space, she says. Semmes’s earlier works have a more regal quality to them; they seem to take a more heroic stance, and appear more restricting. For instance, in Green Sleeve, 1994, the sleeve seems heavy – pulling the weight down, and by 2011 in Red Leaf, Semmes – tired of the pulling, cuts the bottom off, making the piece less bound. This cropping moves the work from having royal connotations, velvet pulling down as some sort of responsibility into more high fashion inspired pieces.

Beverly Semmes, Green Sleeve. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes & Samson.

Semmes’s later work seems less heroic and not so constricted. The dress forms hang like paintings, the wall serving as figure ground, pined to the wall with T-pins as space keepers suggesting experimentation and openness. The pins propose questions of impermanence: they can be pulled out and the works can easily be rolled up and leave the room. I spoke with Semmes about the ephemeral and flexible qualities in the dress forms, and the shapes they take as they move from space to space. I wondered what (installation) form would they take if handled by a different person, of a different discipline, culture, or experience – how would the work command the space ? How would the newly interpreted work change the image of the “Bitch” or the “Puritan”? Would these new works still be Semmes approved?

Beverly Semmes, Red Leaf. Courtesy of Beverly Semmes and Samson.

Beverly Semmes Wild Child is on view at Samsøñ through May 27, 2017. To learn more about Beverly Semmes visit samsonprojects.com or beverlysemmesstudio.com