I shall always be grateful to Honduras, though for it has given me back myself. I am my old brash self again.

-Zora Neale Hurston, Puerto Cortes, Honduras, May 20, 1947

Zora Neale Hurston's "Their Eyes Were Watching God," 1937.

Being a fan or scholar of Zora Neale Hurston renders so many gifts and challenges. Ever since I first read her classic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, and Carla Kaplan’s almost 900-page annotated collection of the writer’s correspondence, Zora Neale Hurston, A Life in Letters, I have been enthralled with an understudied 10-month period in this prolific artist’s life.

It’s an enchantment that is fueled by my desire to understand the geopolitical contexts that have shaped my own familial dynamics, which are rooted in the history of Honduras, Belize and the Caribbean by way of The Middle Passage. During my final year of grad school is also when I first began figuring out how to incorporate these narratives into my studio practice through an installation called “Banana Republic: Conflations and Migrations” which revealed the history of United Fruit Company and its ties to Boston. So it’s fascinating to know that between May 4, 1947, and February 20, 1948, Hurston, a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance lived in my family’s hometown of Puerto Cortes, a port city located on the northeastern coast of Honduras. What makes it all the more astonishing is that the Hotel Cosenza, where Hurston would lay her head on some nights, also happens to be where my great-grandmother, worked as a domestic.

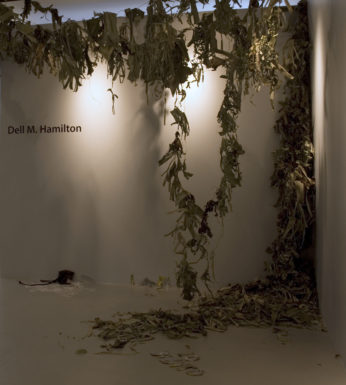

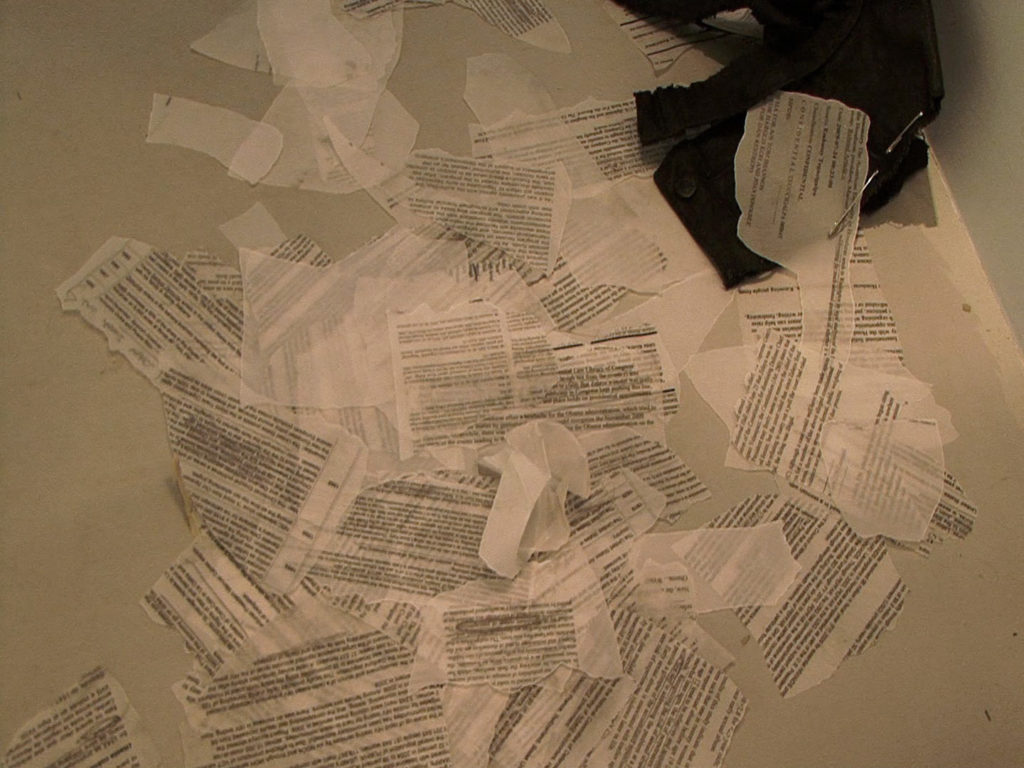

Dell Hamilton, "Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations," coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Daisy Patton.

Because Hurston was an interdisciplinary scholar and artist before there was even a name for that way of working, much has been written about her storied life. Besides Hurston’s own words captured in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, published in 1942, there are three other notable texts: Robert Hemenway’s Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography (1980), Valerie Boyd’s, Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston (2004) and Virginia Lynn Moylan’s Zora Neale Hurston’s Final Decade (2011). All of these books beautifully detail the ups and downs of being Zora.

However there is a dearth of scholarship that deeply considers her time in Honduras. While Hurston didn’t want her colleagues at Columbia to get wind of her visit, contrary to popular history, her passion for Honduras validates scholar Gwendolyn Mikell’s assertion that she never shed her training as an anthropologist. Her zeal signaled a commitment to breaking new ground in the discipline because like the Maya, the civilizations of La Mosquitia are now considered some of the earliest inhabitants of MesoAmerica. I also believe Hurston’s plan was to integrate the research she conducted within black communities in the U.S. and the Caribbean with the broader connections to Afro-descended communities in Central America.

For the peripatetic Hurston still had something to prove when she insisted that Honduras was “untouched” and offered material that was “exceedingly rich, varied.” [1] Beginning in 1944, (the year of my mother’s birth), she wrote furiously to friends, patrons, colleagues and foundations outlining her plans to undertake a two-year study of not only Honduras’s indigenous Afro-descended societies and autochthonous Indian populations, but to also locate the legendary “lost city” colloquially known as La Ciudad Blanca, (The White City). In a letter to fellow anthropologist Ruth Benedict, Hurston writes that she is interested in three different communities: “Black Caribs,” (their present day progeny are Garifuna of both African and Carib indigenous Indian ancestry), “Zamboes” (of both African and Miskito Indian descent) & “Icaques” (an Amerindian population that Hurston describes as living near the mountains in Cedros). [2]

Zora Neale Hurston Beating a Haitian Maman drum, 1937.

Hurston also writes that her informant, Reginald Brett, who has been gold mining in British Honduras (Belize) for many years, has encountered “phenomenal ruins.” [3] Brett had probably already heard of earlier reported expeditions by New Bedford-native Theodore Morde, who in 1940 falsely claimed that he had found the “Lost city of the Monkey God.” Prior to Morde, Captain R. Stuart Murray also led expeditions to find the “lost city” hidden in La Mosquitia.

Just two years after WWII, she writes to her editor at Scribners, Maxwell Perkins, (best known for nurturing the talents of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald & Thomas Wolfe). “It is very interesting here from a writer’s point of view. I am not disappointed in the venture. I confess to being frightened over inflation here. It is a little different from our U.S.A. in that respect. I feel half-stranded already. I shall always be grateful to Honduras, though for it has given me back myself. I am my old brash self again.” [4]

Hurston was certainly right about the kind of impact that Honduras could have on a writer, for between July 1896 and January 1897, American short story writer O. Henry (William Sydney Porter) absconded to Honduras in an effort to thwart authorities who had charged him with embezzlement. During that period, Porter holed up in a hotel in Trujillo (about 250 miles east of Puerto Cortes), where he wrote Cabbages & Kings, a novel set in the fictitious Central American country of Anchuria for which he invents the term “banana republic” to describe an unstable Latin American country whose economy is myopically tied to one crop.

Writing to Henry Allen Moe at the Guggenheim Foundation in 1944, Hurston names two other communities that she is interested in learning from: the Paya describing them as “the most primitive in all of Central America” as well as the Maya. [5] What’s striking here is Hurston’s use of the word “primitive.” In every context, both past and present, the history of the word “primitive” remains racist and problematic. Was her use of primitive in relation to a group’s aesthetic values or did it have to do with social isolation and limited interactions with Americans and Europeans? Since she suggests administering anthropometric studies, how would her research have been impacted by her exotification of these communities? [6]

Carl Van Vechten, "Zora Neale Hurston," 1940.

When considered in the context of Hurston’s earlier research, I would wager that she was most likely the first African American woman anthropologist, if not one of the earliest, African American scholars to travel to the region to document these communities. However since Hurston was stymied by a lack of funds and torrential Honduran rains, how might she have framed each group’s distinctiveness? How might she have framed the impact of genocide, slavery and colonization on indigenous and black diasporic cultures in Central America?

After the death of Maxwell Perkins, Hurston writes to her new editor at Scribners, Burroughs Mitchell, and claims that she has already traveled part of the way to an area that is “practically unknown” and that she has made a “most sensational discovery, which I am keeping under my hat until I get hold of a few hundred dollars.” [7] Here we are left pondering about precisely what kind of discovery was Hurston referring to?

Since the 16th century, the narrative surrounding La Ciudad Blanca has entranced numerous colonizers, explorers and scientists. However for most, any talk of the lost city was simply rumor and myth. Perhaps this is no more evident than in the fact it’s only her advances from Scribner’s that provides funds for Hurston to make the trip. Regardless of the skepticism, Hurston’s instincts were dead on.

In 2013, more than 50 years after her death, through the use of LIDAR (a light detection and ranging technology), sophisticated structures in La Mosquitia were located by archaeologists in areas T1 and T3. The story of this momentous find has been detailed by best-selling writer Douglas Preston in a book published earlier this year, The City of the Lost Monkey God: A True Story.

While still in Puerto Cortes, Hurston also wrote her last published novel, Seraph on the Suwanee, which takes place in Florida and depicts the lives of a white couple, her first book featuring white characters.

Dell Hamilton, "Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations," coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Daisy Patton.

As I’ve undertaken my own sleuthing regarding this period in Hurston’s life, the conclusion is that more hasn’t been written about this period because she was never able to collect enough material to package into a volume of research. The manuscript that was inspired by that period, The Lives of Barney Turk (also featuring a white protagonist) has never been located and was declined by Scribner’s despite the fact that they optioned the book and beginning in 1948 began paying her an advance of $400 over ten weekly installments. [8] And finally, the editors of glitzy travel magazine, Holiday, found Hurston’s photos “uninteresting” and her article on the Spanish-built 18th century fort in Omoa, Honduras, “too diffused”; the photographs, negatives and text for this article have not been located. [9]

There is also the fact that upon Hurston’s return to New York to work on edits with for Seraph on the Suwanee, she was arrested and falsely accused of molesting a 10-year-old boy. Hurston was devastated by the “morals charge” and felt betrayed by the Baltimore Afro-American for publishing the erroneous story without her comment. Most bizarrely, the molestation is said to have occurred over a period of a year, which actually turns out to overlap with the months that she was in Central America. In other words, Honduras is Hurston’s alibi.

If my prayers hold any sway, one day the Barney Turk manuscript, more field notes or the photos from this period will turn up, and I will need to thank the universe for solving a fascinating mystery.

Dell Hamilton, "Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations," coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Angela Counts.

- Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” 1937.

- Zora Neale Hurston Beating a Haitian Maman drum, 1937.

- Carl Van Vechten, “Zora Neale Hurston,” 1940.

- Carla Kaplan, “Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters,” 2003.

- Valerie Boyd’s “Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston,” 2004.

- Dell Hamilton, “Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations,” coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Daisy Patton.

- Dell Hamilton, “Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations,” coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Angela Counts.

- Dell Hamilton, “Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations,” coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Daisy Patton.

- Dell Hamilton, “Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations,” coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Angela Counts.

- Dell Hamilton, “Banana Republic: Conflations & Migrations,” coat hangers, banana leaves, paper, thread, plastic, denim jeans, Photo credit: Angela Counts.

[1] Kaplan, Carla, Zora Neale Hurston, A Life in Letters, Anchor Books, 2002, page 506.

[2] Ibid, pages 196-197.

[3] Ibid, page 445.

[4] Ibid, page 549 (May 20, 1947).

[5] Ibid, pages 504-505 (September 18, 1944).

[6] Ibid, page 197 (letter to Ruth Benedict).

[7] Ibid, page 553-554 (July 31, 1947).

[8] Letters of Burroughs Mitchell, Author Files, Charles Scribner’s Sons Archive, Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University.

[9] Card File, Watkins-Loomis Records, Rare Book and Manuscripts, Butler Library, Columbia University.