Observance: As I See You, You See Me (up through April 8 at the Montserrat College of Art Gallery in Beverley, MA) is an exhibition of portrait photography that features multiple viewpoints on identity. Curated by Leonie Bradbury, the variety of portraits creates a provocative exploration of how judgments are made based on a person’s skin color, physical appearance or clothing choices. The exhibition is timely, with identity politics under attack and hate crimes on the rise. In this tense moment, the show implicates the viewer: how do I see you? How do you see me?

Juan Jose Barboza-Gubo and Andrew Mroczek, "Andreina & Sarah Nicolle," archival inkjet print, 2015.

Juan Jose Barboza-Gubo and Andrew Mroczek create striking portraits of transgender women from Peru. The large photographs are hung close to the viewer’s eye level so that we are looking directly into the subjects’ eyes. Nazia is formally posed. She is wearing a black lace mantilla, making a direct reference to colonial oil painting. Above her head a wreath of red roses glows in the darkness like a crown. In a double portrait, two young women, Andriene and Sarah Nicolle, look steadily at us from an ornate but decaying mansion. Oil paintings are stacked behind them. We see marble floors, tiles and peeling wallpaper. In a surreal detail, the sisters’ long braids trail onto the floor. Their nail polish introduces tiny points of color and individuality. Between these two portraits hangs Leyla, portrayed nude with a delicate handmade halo and a long lace bridal train. These religious symbols transform the portraits into icons. Together the placement of the three photographs suggests an altarpiece.

The religious iconography and colonial interiors in Barboza-Gubo and Mroczek’s portraits on the one hand celebrate Peru’s rich artistic history, and on the other they critique a class structure that privileges Spanish ancestry and the powerful role of the Catholic Church. Situating these portraits in relation to beauty, religion and history is both empowering and subversive because it points to the opposite experience that transgender women receive in contemporary Peru. That a man can change into a beautiful woman is deeply unsettling in a country with a strong religious and social belief in traditional masculinity. Transgender women suffer violent attacks and abuse, including murder. Men who transition to women are particularly vulnerable because their very existence undermines and threatens Church teaching. They also suffer from a law that forces them to list their birth or biological gender on identity cards. Identity cards are required to be carried at all times and must be used to access health care, making it extremely difficult to access basic health services.

Caleb Cole, "February is Dental Month," archival inkjet print, 2008.

Gender roles and how they are coded in clothing, occupations and environments are poignantly examined in Caleb Cole’s series Other People’s Clothes. As the title suggests, he begins by dressing up in someone else’s clothes and then creates a narrative about that person’s life. Cole also pays meticulous attention to the constructed environments in his portraits. In February is Dental Month, we see Cole wearing a yellow turtleneck under a bright green sweater, gazing glumly out from behind an enormous desk in a dental office. In another portrait, Cole wears an oversized cardigan and sits on a bench next to a planter, alone in a public place. These photographs are a meditation on loneliness. They also expose stereotypes and the assumptions and narratives we create about other people. What does clothing project? What are the assumptions we make about other people based on appearance and occupation? How do we judge others and, in turn, how are we judged?

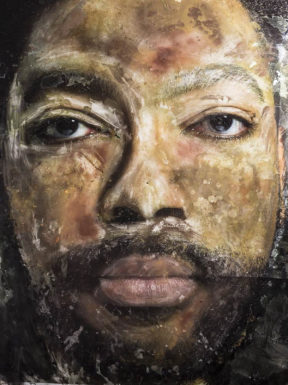

Ervin A. Johnson, "Ervin," from the series #InHonor, photo-based mixed media, 2015. Courtesy Arnika Dawkins Gallery.

Ervin A. Johnson expresses the pain and suffering of black men brutalized by police in two large mixed media portraits. The portraits are of Ervin and Joshua from the series #InHonor. Their large format and tight cropping draws attention to the men’s eyes and lips. The artist’s removal of the subject’s skin color transforms the portrait into a visual record of pain and anger. A residue of stains, drips, splashes, splotches and expressive brush marks covers the surface of the paper. Johnson has talked about the expressive painterly quality of his work and how the marks emerge from a psychological and physical struggle with his material and with the need to express his pain at the loss of black life due to police brutality.

Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons also addresses issues of race and identity in several poetic self-portraits. In three related photographs titled Songs of Freedom her head is trapped in a birdcage–a symbol of freedom and captivity. Her face is hidden at times and her eyes closed suggesting a dream-like and metaphorical meaning to these portraits. They relate to her life story and to the history of Cuba where she was born before migrating to the United States. The white paint on her body references the Yoruba rituals of her ancestors transported from Nigeria. In a photograph from a different series, the artist is dressed in Chinese robes that allude to Chinese heritage through her mother. These performative photographs explore the artist’s multiple identities.

Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, "Songs of Freedom," C-Prints, 2013.

A series of polaroid portraits by Dead Art Star portray a group of artists and friends experimenting with different personas. The polaroid format intentionally references Andy Warhol’s use of the polaroid to document his life and photograph his friends. The subjects pose for the camera. These portraits of relationships and collaborations suggest the freedom to be oneself or try on other selves. The portraits are deeply romantic, capturing a group of people at a moment in time. The diminutive scale of the photographs requires the viewer to get up close to see the images. The self-awareness of the subjects gives a voyeuristic feeling, reinforcing the implications of looking and being looked at that inform the entire exhibition.

This is a beautifully curated show. We are aware of the artist behind the camera in each of the portraits. However, the individual voices gain significance in the context of the other works in the exhibition. These portraits create a larger conversation about representation and identity that, when placed together, grows in complexity and meaning.