DRAW/Boston, an exhibition of over 60 artists curated by Tomas Vu, toys with scale, color, style, and sound, wedding the scholarly air of a professional university gallery with the aesthetic resemblances of a working artist’s studio. The arrangement alone warrants questions of intent and reason, and with such a broad interpretation of ‘drawing,’ the diverse spectrum of techniques exhibited requires a premeditated understanding of the creative process.

Upon entering the Bakalar & Paine Galleries, a monochromatic, cacophonous crowd of faces and people are illustrated on a plywood canvas stretching from floor to ceiling. Like a cinematic montage flipping through decades of newspaper photographs, scenes depicting abuses of power blend together. Masses of people holding signs in protest, police in uniform shoving a person of color to the ground, MLK at the grandstand, even a graphic of Donald Trump shouting. The piece is titled Demonstration Drawing, an interactive and ever-evolving mural where the public may add to the collage of social injustices by drawing from a previously compiled selection of images. The artist, Rirkrit Tiravanija, activates the space by unifying the role of the viewer and artist, bridging the gap that separates work seen in a gallery and work which exists in the artist’s studio. Throughout the exhibition, this theme re-emerges in style, medium, and sequencing.

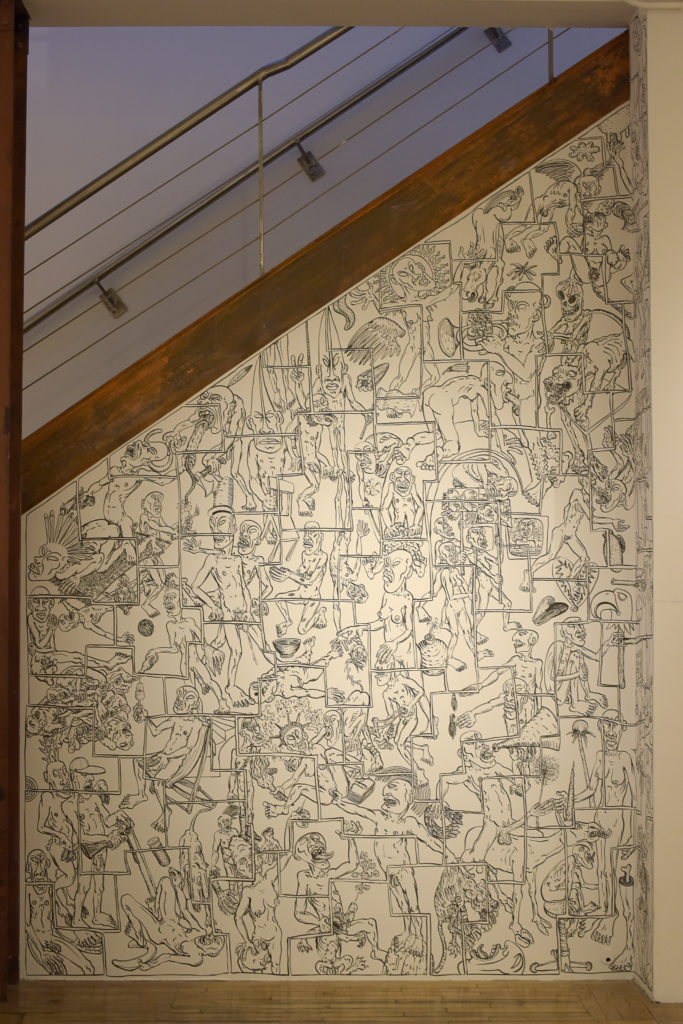

Heimo Wahner. Image courtesy of the author.

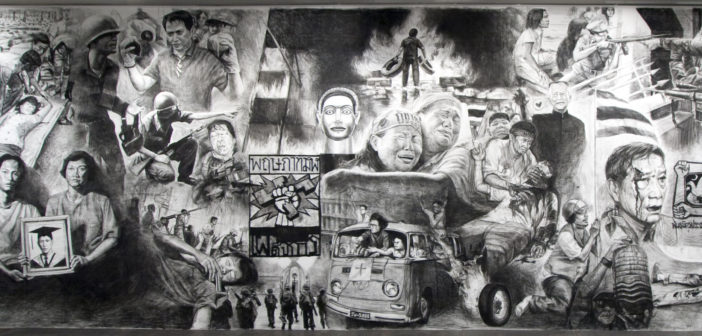

A selection of seven artists, including Tiravanija, took part in creating seven murals in the first room of the gallery. All are charged with social or political retaliation, poetically installed on and around Inauguration Day. Painter Chris Jehly’s amorphic portrait of Batman is in direct response to this. The Batman mask is all we can derive from the image, as the ‘face’ of the beloved superhero folds in on itself in tumorous blobs of flesh, distorting anything resembling features. It is a projection of the frustration and fury felt by both billionaire Bruce Wayne and vigilante Batman of the election of Donald Trump. Heimo Wahner’s mural is a wildly busy jigsaw puzzle of people sporting symbolic icons of government, religion, and culture, taking part in violent and sexually charged acts. One body wears the crown of Lady Liberty squatting nude above another whose penis has transformed into a shotgun. Frustration and its reaction ripple throughout the exhibition and flows subtlety into the rest of the space containing the remaining artists and works.

Smaller, oddly sequenced works fill the second room of the exhibition. Our introduction to this new world is a wall of cluttered work, some attached with tacks and magnets, others with strangely sculpted pins made to look like stone. Brian Novatny’s loud color washes on creamy paper appear more like a color test palate than a work made for a gallery, though strange minuscule qualities pull the eye in. Fine details of pen and ink trace the incredibly intricate and precise lines of body parts and biomorphic shapes, conforming to the bulbous drenches of color. We are fed dark scenes as if through a child’s eyes of wandering outside at dusk by Cary Hulbert, and floating high above is a print by Kiki Smith illustrating a study of bats. It is a disparate array of images, processes, and styles lacking continuity.

In with yet another play on scale, William Kentridge presents a life-sized tryptic reminiscent of Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, though, upon closer inspection, the body language of what may be Donald Trump nude, dancing with a mysterious partner comes into view. Kentridge’s slashes of ink on paper and mylar exhibit an aggressive movement between the three the pieces and pushes the eye towards the work of Steve Locke. Locke, a local, Boston-based artist, exhibits his bright watercolor faces extending lolling tongues seemingly caught mid-yawn or cough explode along the wall in decadent frames cradling vibrant mattes.

The over indulgent salon style continues through the exhibition, some pieces dangling lonely on the wall, while others nearly overlap one another. Works both framed and free floating speckle the space as though hung as an afterthought. A sculpture by Tory Fair—what looks like handmade paper holding a moderately sized sphere of granite—sits a mere foot from the floor. It directs the eye down as one rounds a wall of paintings, drawings, etchings, textiles, and alternative processes of illustrating. After examining and questioning the arrangement of works, a light, almost comical air to the show reveals itself. It appears subtle at first—almost accidental—until the exhibition lets us in on the joke; this is not a show for just any viewer, this is one designed for artists.

Installation shot of DRAW/Boston, courtesy of the author.

The chaotic splatterings of pieces tacked on the walls mirror the workspace of an artist’s studio and the natural process of developing work to which the artist adheres hope, promise, and pride. “DRAW” stretches its definition beyond merely the illustrative term of drawing, as each artist draws opinions, conclusions, and on experiences to react to social identities, political climates, and our very intake of information. Once this is made apparent, the show falls into place and the viewer may greater appreciate the variety exemplified. The identity of each artist is written with chalk beside each piece, which lacks all information we expect to see attached to works of art in a gallery. Without titles, dates, or medium, the responsibility of the viewer to form their own understanding of content and context is crucial.

The nature of the show flows from works depicting people into a breakdown of shapes, color fields, and basic elements of structures. From collaged paintings of old side-show attractions blaring phrases like “Bearded Lady” or “Pig-faced Lady” by Jennifer Nuss to Jason Kravs’ piece—hung so high it is unable to be studied, reminiscent of the night’s sky with a light dusting of stars amongst the black paper. Icons and symbols are manipulated in the works of Xu Wang, who illustrates the animals of the Chinese Zodiac with sugar and melts the surface to give it a resin coated effect and Carl Fudge whose framed representations of TV static are mounted high on a wall. Soundscapes incorporating harpsichord, dial tones, pages flipping, and guttural vocals, among others, fill a small room attached to the main entrance, where a slew of animations play. The Babel Cycle by Nikola López ties elements of architectural blueprints of unplaceable ancient cities to the frolicsome nonchalance of doodling in a sketchbook, building shapes upon structures and dilapidating back down to a blank canvas behind a well-composed score. Another video, by Jessica Segal, is animated with a blackboard and illustrates the lessons of physics, the journey of light, and the functions of seeing using elegant detail from 19th-century medical and scientific textbooks.

Hidden intentions and subtle curatorial details weave the viewers of DRAW/Boston through a space designed to leave them asking questions. Highlighting a diversified array of art through a challenging installation, this show activates the galleries by giving the inquisitive eye a bounty of material. From start to finish, DRAW/Boston delivers a journey through the eyes of the artist in thought and process.