My favorite piece in the 2016 edition of the Montreal Biennial was also the oldest by nearly five centuries: Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Portrait of a Lady. Like any anatomically correct 16th century woman, her waist is the width of her neck, she seems to be side-eying the suite of amazingly boring Luc Tuymans paintings of empty galleries on the wall adjacent, and her right arm, which looks long enough to reach her kneecap, is crooked bizarrely out to her side. The painting’s intrigue, the wall text tells us, is in this arm or what lies underneath it: she supposedly once held a plate displaying the severed head of John the Baptist. The head made the painting unsellable for 20th-century collectors, so it was painted over. But x-rays taken of the painting in the 1970s at the Canadian Conservation Institute revealed no head, leaving the meaning of the image in limbo. Which is more mysterious, the painting’s secret image, or that its sole condition for inclusion in the Biennial was that it was touched by Canadian hands? In this bizarre curatorial move, the x-ray becomes a creative act.

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Portrait of a Lady.

Portrait of a Lady was one of the few works in the Biennial that seems relevant to curator Philippe Pirotte ’s introductory text, which cites the balcony in Jean Genet’s play Le Balcon as a place of uncertainty, where identity is never fixed. The show, Pirotte writes, aims “to develop an unruly and recalcitrant space that gives form to an aesthetics of resistance to the violence of quantification and categorization, and to the violence of naming and controlling.” Basically, if I understand the artspeak correctly, nothing is what it seems and nothing stays put, and these qualities make for something untameable in an artwork.

Installed in the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MAC) and other art spaces is a balanced mix of installation, sculpture, video, and painting, with a smattering of text and photography, but little in the way of post-internet art, new media or artists’ publications. As for public art (call it social practice, community engaged, or participatory art), which seem to me the medium best suited to fulfilling the curator’s aim in destabilizing categorization, look no further than the public art piece--not part of the Biennial-- in the park across the street from MAC. Consisting of oversize wheels that participants can sit inside to push a crank that spins images around the inner rim, it turns the park into a series of human-powered personal film projectors and seemed wildly popular even in ten-degree weather. Jean Genet’s balcony, perhaps, is by definition located outside of the institution.

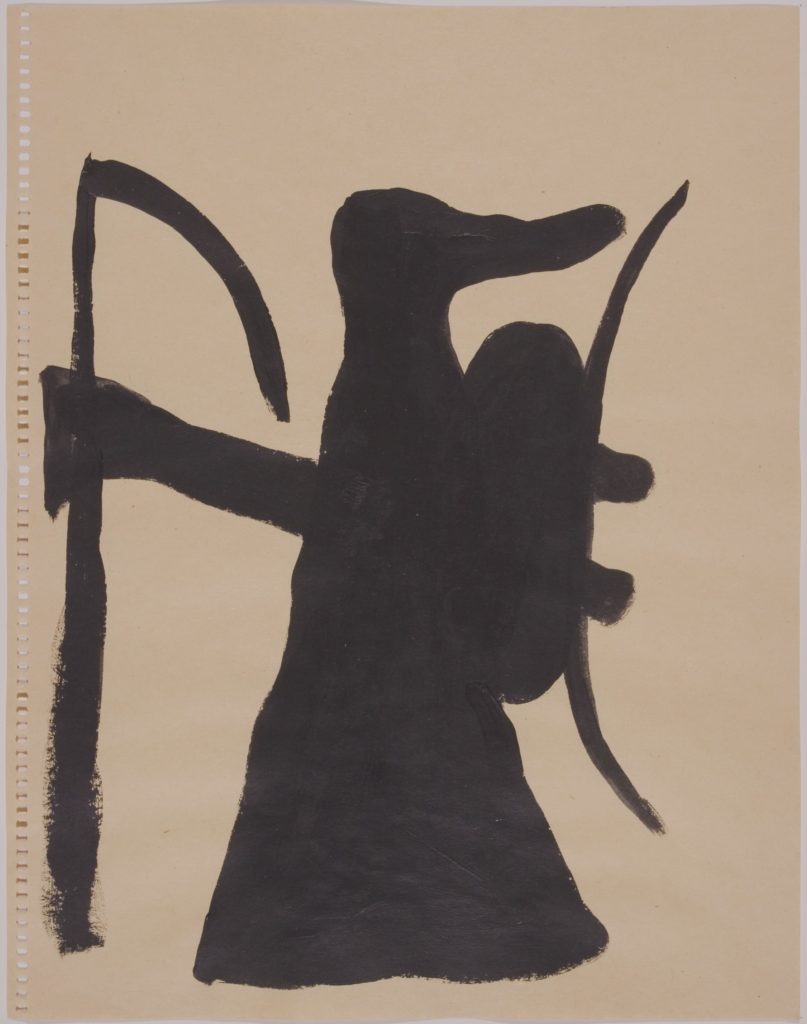

This Biennial delivers on the promise of its form, to pad out the big names with the local ones, thus putting some Quebec artists on the international stage. Isa Genzken’s circled-up mannequins are the eye of the selfie-storm in one room, while Haegue Yang’s basket-like orbs dominate another. But the Biennial is also useful as a litmus test of what’s trending in contemporary art, here presented through a slightly Canadian lens. In sculpture, where the mystification of commercial objects is in, Montreal-based Valerie Blass stiffens a pair of blue overalls cut down to its seams, so as to imply and abstract the shape of a body. In video and performance, where everything is reenactment, Myriam Jacob-Allard records amateur singers she meets at a local bar performing their singing karaoke favorite Canadian country songs in their best just-performing-for-the-webcam faces. And in contemporary painting, a discipline here as elsewhere in the shadow of Nicole Eisenman, whose work is stationed at the entrance to the second-floor galleries, are Geoffrey Farmer and Brian Jungen’s wonderful cartoonish grim reapers. Painted into winter sport magazine spreads, they have snowboards strapped to their backs (could there be a more Canadian way to translate the post-Guston graphic turn?).

The Lost Drawings of Geoffrey Farmer and Brian Jungen, 1995-96/2002. Watercolour, acrylic and collage on paper. Collection of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia. Anonymous gift.

Moyra Davey’s Hemlock Forest struck me as the only intimate work in a sea of pieces that seemed pre-packaged in their wall texts. The forty minute film, which debuted at the Biennial, is a rambling and diaristic look at the artist as a fifty-something-year-old woman and the influence on her work of Chantal Akerman, the filmmaker who took her own life the day after Davey re-shot her subway scene. We see the artist’s twenty-year-old son with his friends, posing with their guns, endlessly readjusting their stances for the camera to meet the perfect caliber of toughness and irony. Then there’s Davey half-naked, seated on her side awkwardly on what looks like a hotel room bed, earbuds in, furiously writing notes with one hand and cramming sponge cake into her face with the other. There are points of comparison to be made with Frances Stark’s practice in the casual filming of artist-as-mother, but where the latter seems glib and a bit annoying, Davey’s approach comes across as an honest and contemplative look at the stuff an artist’s life is made of.

Installation view, Moyra Davey, Hemlock Forest, picture by Daniel Roussel, courtesy of La Biennale de Montréal.

But the (contemporary) piece that was most haunting to me was David Gheron Tretiakoff’s A God Passing. The twenty-minute film cuts between TV and live footage documenting the transportation of a thirty foot high stone statue of Ramses from the Cairo train station to a museum. Strapped to a flatbed truck, hemmed in by scaffolding and preceded by security vehicles, the face passes slowly between the thoroughly modern high-rise buildings. Drawing crowds that line the streets and hang from their balconies to watch, the procession gathers a ritual significance and becomes an event where national identity is contested among the civilian audience.

How do you reconcile a thirty foot high hand-carved stone statue with its mass broadcast on ubiquitous TV sets, let alone the eternity of cell phone cameras capturing its likeness? Like the presence of Cranach the Elder’s Portrait of a Lady in a Biennial--a form dedicated to the contemporary, but perhaps reaching its expiration date on its ability to deliver it-- points to some kernel of truth at what’s afoot in contemporary art: the bizarre relationship of the old mediums to our present super-saturated muck of commercial images.

Installation view including works by Valérie Blass, picture by Daniel Roussel, courtesy of La Biennale de Montréal.

The Montreal Biennial closed on January 15, 2017.