Characterized by its elongated horizontal size and finely articulated details, the panorama was originated as a painting format in the nineteenth century. In a time of fevered nationalism, many of these paintings were government commissioned to project a particularized state identity, glorifying technological advance through verisimilitude in paint. Often the paintings intended to illuminate a subject encompassed by a series of events, not just one particular moment. As a result, the painting was a synthesis of different events as they occurred throughout different spaces at different times. Even when the scene depicted was something encountered an everyday experience, people would flock for a chance to see how closely it represented reality. The panorama had a dual function to present both history and spectacle. Even after the panorama (and its many manifestations) lost its appeal, the desire for this type of dramatic fidelity would later live on through photography and the cinema.

The ghost of the panorama is a familiar sight today. Many of us have encountered this extra option while fiddling with camera settings and when scrolling through the format menu on a television. Though understated compared to the spectacular buzz surrounding the original panorama, John O’Reilly’s images are a fitting, reticent tribute to this showpiece, nearly two centuries old.

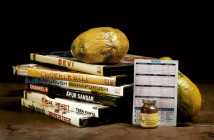

Featured this month at Howard Yezerski Gallery, Panoramas is the latest series in an ongoing, forty-year collection of photographic montages made by O’Reilly. A 1956 MFA graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, O’Reilly’s past work has shown throughout the country, including the 1995 Whitney Biennial. The collages were created from cut fragments of singular Polaroid photographs that depict snippets of famous paintings, antiques, views through windows, cut flowers, marble statuary, anonymous snapshots, and various portraits of the artist himself. Separated from recognition of its original spatial context, the images on the Polaroid bits are carefully reconstituted into a fabricated scene. The illusion of space created by these collages emulates a chaotic still life that one could only replicate by neglecting to clean an attic.

Looking closer, the seams of the montage become apparent. The fidelity some Polaroid pieces are affected by oxidation. White edges on the Polaroids are exposed from cutting its paper base. Recognizing the seams in these transitions, the perception of space is cancelled, rendering it temporarily flat. Though, these clues that defy the illusion don’t betray the cause of that effect. Convincingly, the slight relief made by overlapping the fragments help to create the illusion of volume and the white edges along the individual pieces mimic the halos caused by the backlighting of an object. By placing photographs of light streaming through windows that appear in the background, O’Reilly can sustain the continuity of illusion. The pasting technique is not technologically savvy, but the method used to arrange the fragments is quite sophisticated.

Nearly as old as paper based photography itself is the need to cut it up and paste it elsewhere. Artist/photographers like Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, John Heartfield, Hannah Hoch, Claude Cahun, and Robert Heinecken have all used creative assemblage to express what could not be contained in the confines of a solitary image. Unlike O’Reilly, these artists sought fragmentation to provoke the prevailing social and political norm. By exposing the shortcomings of photography’s inclusive description, they could express ideas previously marginalized within the ruptures of that exchange. The montages made by O’Reilly’s disguise this disjunction, making the image appear whole despite its seams. Fragmenting the temporal placement of autobiographical history with objects that look like history, O’Reilly reconstructs a new perception of his identity in which we imbue our recognition of the artist with references like Greek antiquity (in Orpheus) and the opera (through Benjamin Britten). Where cutting up pictures was once an act of defiance, O’Reilly’s verisimilitude transforms the act into a desire for inclusion within a particularized history.

- Studio Garden in Winter; 6-8-03; Polaroid Montage; 3 3/4 x 14 7/8 in.

- Orpheus Suite #26; 1-17-03; Polaroid Montage; 3 3/4 x 19 15/16 in.

- Around Benjamin Britten; 4-27-03; Polaroid Montage; 3 3/4 x 19 in.

Links:

Howard Yezerski Gallery

"John O'Reilly: Panoramas" is on view through May 4th at Howard Yezerski Gallery.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Howard Yezerski Gallery.

Matthew Gamber is a regular contributor to Big, Red & Shiny.