She agitates

the quart developing tank

in total darkness,

our windowless bath;

the cylinder slides

inside against the film

for ten minutes

at 70 degrees.

I can see the developer

acid in the luminous

dial of my watch:

she adds the stop bath

The hypo fix

fastens the images

hardening against light

on her film and papers.

I imagine her movement

at night as her teeth grind:

I know she dreams the negatives.

-"The Negatives," Michael S. Harper

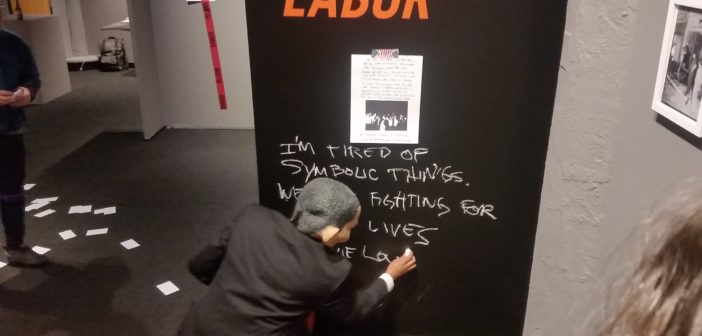

I am tired of symbolic things. We are fighting for our lives.

-Fannie Lou Hamer

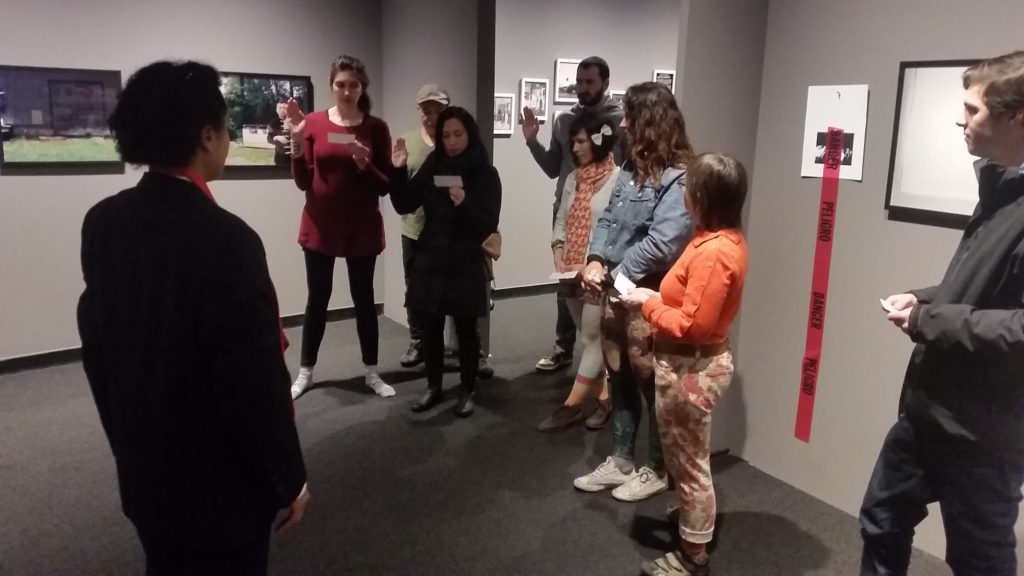

Dell Hamilton, "I Question America, I Question Us," performance at the Photographic Resource Center, courtesy of the artist.

My practice evolves through constant research and reflection. I use art making, much like writing and reading, as tools for both expression and thinking.

I have discovered that the efficacy of writing after a performance (a tip I learned from fellow artist Marilyn Arsem) is productive towards discerning the why and the how of my decision-making process.

The process of art making is also a personal way to test ideas within and against time constraints as well as the social conditions under which I am subject to, the individual characteristics of materials, and the site-specificities of a particular venue.

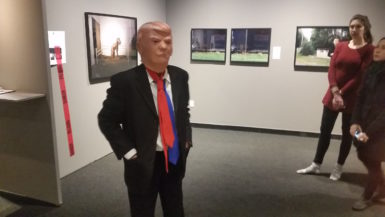

As an example, for a new performance entitled “I Question America, I Question Us” (presented at the closing reception for the “Race, Love and Labor” exhibition at the Photographic Resource Center in Boston), I took advantage of the fact that the performance was scheduled within days of when President Obama left office and peacefully transferred power to the 45th President of the United States.

Among other questions, in creating “I Question America, I Question Us,” I considered: How to playfully “perform the presidency”? How might I deconstruct the choreography & color of patriotism? How to amplify the absurdity of this new political landscape and its implications for allegiance and democracy? What enables language to perform difference and impermanence? And how might I embrace the didacticism of protest art?

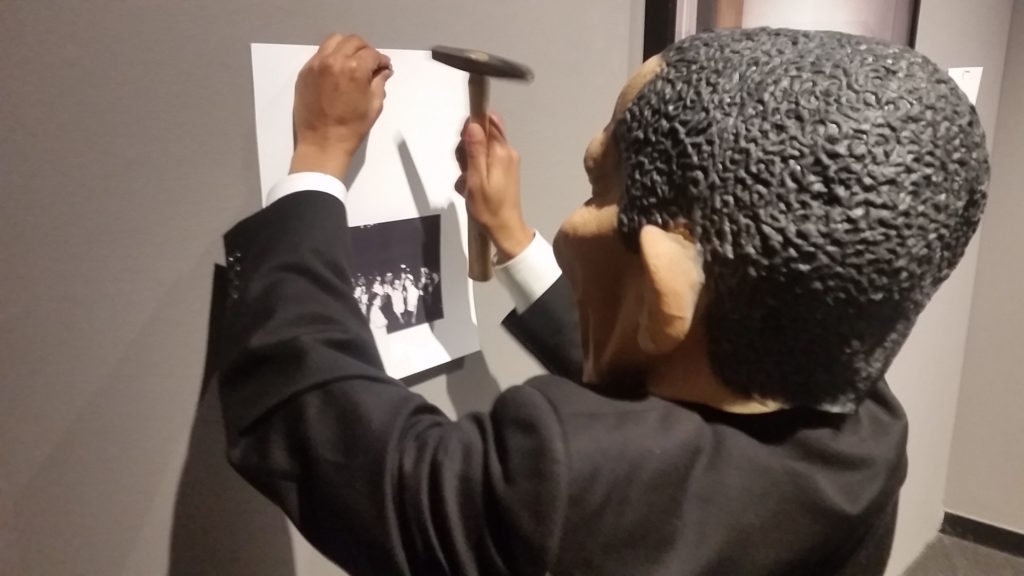

Dell Hamilton, "I Question America, I Question Us," performance at the Photographic Resource Center, Photo credit: Bruce Myren.

When beginning a new project, I also remind myself that I am calling an idea into being (as if I were naming a child). To do that I often start by reading and researching and then I do what I call “name it & frame it.”

Recurring themes continue to inform my process and that includes my interest in the term post-democracy coined by Colin Crouch in 2000—(a post-democracy is a society that continues to have and to use all the institutions of democracy but in which they increasingly become a formal shell).

Dell Hamilton, "I Question America, I Question Us," performance at the Photographic Resource Center, Photo credit: Bruce Myren.

When I pondered what to name the piece, the questions noted above also reminded me of an impassioned speech that civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer delivered at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City.

In 1964, Hamer was the Vice Chairperson for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and demanded that the party replace the then installed all-white Mississippi delegation. During that fateful visit to Boardwalk Hall, Hamer’s image was televised as she outlined the violence she suffered while in jail after being arrested in 1963 for attending a voter registration workshop. Hamer goes on to say:

"All of this on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens. And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America."

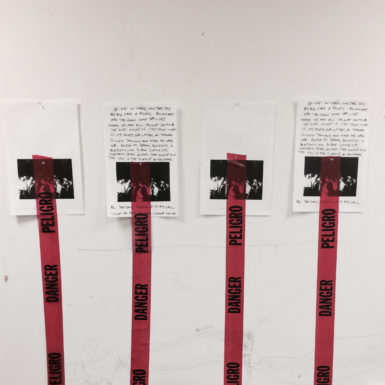

As I began to further develop the work, I delved into the “Race, Love and Labor” exhibition catalogue and noted curator Sarah Lewis’s assertion that it is impossible to separate the history of photography from the history of labor (which was quite evocative of my habit of calling something into being). Lewis writes: “It is not work but labor: a means through which we birth ourselves anew.”

Gene Sharp, "How Nonviolent Struggle Works," Albert Einstein Institution: 2013.

In addition to this text, I poured over the words and images of Citizen, An American Lyric, written by MacArthur genius winner Claudia Rankine.

I had been trying to incorporate Rankine’s book into my work for at least a year. But a solid idea would not take shape. However, this time around, I became fixated with a Photoshopped image that appears in the book on page 91.

The original image was created in 1930 in Indiana and functioned as evidence of the grisly lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. I’d seen this image too many times to count. But in this re-worked version (which I had reprinted into 11x14 digital prints for the performance), Rankine erased the broken bodies of Ship and Smith so that upon seeing the picture again, I focused on the spectacle of torture that was rendered in the facial expressions and gestures of the white men and women. Printed in Rankine’s book, the image is arranged in such a way that it takes up only the lower half of the page, while the top half of the page remains blank.

Again I am reminded of Roland Barthes’ theory of the punctum as well as the reproductive capacities of image making and their relationship to the redaction of history. Wrestling with these implications continues to inform my understanding of where we find ourselves both individually and collectively in 2017.

As shock events accumulate and the impulse to define and reconfigure nationalism and civic engagement in the face of geopolitical uncertainty intensifies, the boundaries between the past, present and future are collapsed in the grammar of public spectacle, rhetoric and optics.

Such is the beauty and rage of Rankine’s poetry and Fannie Lou Hamer’s words as they trawl through the contingencies of my own imagination, between who is or isn’t made visible, and my inability to “make sense” of America’s brutal realities and contradictions.

Dell Hamilton, "I Question America, I Question Us," performance at the Photographic Resource Center, Photo credit: Bruce Myren.

- Dell Hamilton, “I Question America, I Question Us,” performance at the Photographic Resource Center, Photo credit: Bruce Myren.

- Dell Hamilton, “I Question America, I Question Us,” performance at the Photographic Resource Center, Photo credit: Bruce Myren.

- Dell Hamilton, “I Question America, I Question Us,” performance at the Photographic Resource Center, courtesy of the artist.

- Dell Hamilton, “I Question America, I Question Us,” performance at the Photographic Resource Center, courtesy of the artist.

- Dell Hamilton, “I Question America, I Question Us,” performance at the Photographic Resource Center, Photo credit: Bruce Myren.

- Dell Hamilton, “I Question America, I Question Us,” performance at the Photographic Resource Center, Photo credit: Bruce Myren.