“For local control all you need is a place, political say and a way to make a living; it’s a practical matter. For local art you need a whole culture.”

Donald Judd, “Imperialism, Nationalism and Regionalism,” October, 1975[i]

Richard Van Buren, a Californian who moved to New York City in the 1960s, studied Spanish existentialism and ceramics in Mexico City before making his way to the Northeast. Fusing Minimalism with an impish hint of Pop cool, three of Van Buren’s sculptures establish the Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s latest Biennial. These works are glossy, their surfaces obscuring a glimmering, furtive, debris of glitter and streamers, scattered in statis. Van Buren is local to Maine, but his work—cultivated over a range of experiences, from Mexico to Maine—reflects a whole culture. It’s a fitting start to this Biennial, which considers the impact of post-truth on the country and society as a whole. In so doing the Biennial demonstrates the strength of art making in Maine, which seems less concerned with actual landscapes than with how our American political landscape is governed and shaped.

Richard Van Buren. From ByPass V, 2016. Resin and mixed materials. Courtesy of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art.

Juried by critic John Yau and dealer Christine Berry, the Biennial’s twenty-five artists work across all media and materials. The work was selected well before the last Presidential election, and none impose any overt politicism. However, a subtle undertone of remonstration reverberates throughout the Biennial through its focus on works that consider perception and how it’s affected by form. It’s all too topical for our current post-truth politics, in which the sway of emotion is stronger than fact.

Emily Brown, Wayward, 2016. Ink on paper, 38 x 52." Courtesy of Center for Maine Contemporary Art.

Emily Brown’s three ink drawings strike an opaque discontentment in the Biennial’s second room. Each a dreamy sight of bucolic woods, radiating the quiet vastness only found in remoteness, these drawings present the interconnection and confusion of vision. Brown’s assured but unassuming mark works edge to edge, her subject entirely foregrounded. Each elongated trunk and branch is somehow distinct but not quite distinguishable, lacing together into an impenetrable scene that is all view but no vista, no forest but all tree. Like calligraphic writing, her strokes are both abstract and not.

Sarah Bouchard’s “100 Whites” and “Somebody Put Baby in the Corner” are similarly a study in contrasts. Bouchard works deftly between painting, collage, sculpture, and installation with a process-oriented approach that searches the parameters of perception. “100 Whites,” is a grid of soft pastel circles, representing a shade of white available from Home Depot, each painted inside a sterile white square. Empirical and pragmatic, this work probes the meaning of “whiteness” in straightforward so-called ‘hard-edge’ geometry. “Somebody Put Baby in the Corner” is a spherical equivalent, composed of 64-clouded balls cascading in a corner, with space for one person to stand within. Once inside, you can see tissue-like texture of each ball and are drawn to consider how they are constructed and connected.

Sarah Bouchard, Orbs Installation, 2016.

Handmade paper orbs, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Center for Maine Contemporary Art.

Bouchard’s unassuming conceptualism diverges with more expressionistic, painterly works by Kayla Mohammadi and George Wardlaw but segues smoothly into this room’s two photographic installations, Tonee Harbert’s six untitled archival prints and Cole Caswell’s “The Source,” a lattice of eighty-one tintypes. With realism veiled in grit, Harbert depicts the decline of buildings and shorelines. In “The Source,” Caswell investigates sun-made patterns in rich hues of black, white, and grays, encapsulating its movements without ever capturing it fully. Like Bouchard, Caswell seems to scrutinize the meaning of natural or social structures that are defined by how they are understood.

In Paul Oberst’ four-channel installation “Banded Measure,” the source of the throaty drone permeating the Biennial, a figure covered in horizontal black and white stripes walks across a stretch of beach. Oberst, who passed away in December, began using the banded figure in his work in the 1980s; here it paces back and forth, in various stages, holding an improbably tall walking stick. Faceless, black and white figure traverses the ochre of the beach until it fades away, leaving us with a rhythm of breaking blue shore. “Banded Measure” emits an earthy, sonorous hum, haunting each gallery of the Biennial. The sound—and the anonymity of figure—ferments a sense of dislocation furthered by the dreamy, abstract elements of the work, advancing an indistinct sense of unease.

Paul Oberst, Banded Measure, 2015. Video (still), dimensions variable. Courtesy of Maine Center for Contemporary Art.

Installed nearby are conflicting suites of painting. On the left are Philip Brou’s hyper-real portraits of middle-aged men, imperfections in all, demurely meeting us at eye-level. On the right are Claire Seidl’s four colorfully and tactile abstractions, each drolly titled. Seidl’s Twombly-esque paintings cheekily convolute process, pictorialism, and psychology. In “Here’s Your Hat,” Seidl seems to have excavated the work’s surface with gestures more scratch than stroke. The surface of “Sometimes I’m Like My Mother” is just as extracted, but enhanced with swaths of dark, black panes. Likewise “Neither Here Nor There” and “What Do You Mean What Do I Mean” are made intricate by ambiguously reductive and additive handling of paint and surface. Together with Brou’s all too real portraits, and Oberst’s four fantastical screens, these paintings obscure the totality of truth. Instead, they present the incomprehensibility of certainty, a post-truth grappling with fact and fiction.

Claire Seidl, Here’s Your Hat, 2016. Oil on linen, 34 x 30." Courtesy of Maine Center for Contemporary Art.

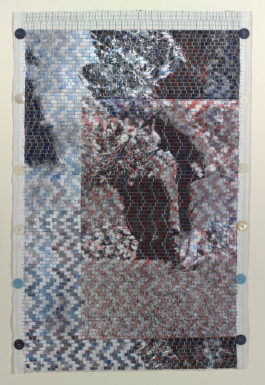

“Alternative facts” are very prophetically confronted in the final gallery with works that test the boundaries of actuality and the complexities therein. A lawn chair—a simple, suburban staple—is facsimile in Carly Glovinski’s “Organizing Behavior,” constructed in paper and correction fluid with a block of wood, painted as a book, in its seat. Glovinski demonstrates that reality is only as what we perceive through inverting abstraction and material. In “The Grand Canyon,” Glovinski presents one of the United States’ most iconic sites as a puzzle with its central pieces missing. With the margins fully complete, we are left to come to our own conclusions as to what jigsaws together to create the center. Nearby, four works from Gail Skudera’s “Big & Little Women” series similarly recontextualize fact and fiction by highlighting the margin. Black and white photographs depicting mid-century scenes of so-called quintessential America are cut into strips and woven back together, bound by thread. Stitching, a usually invisible, marginal facet of clothing here becomes central to the picture through its obfuscation. If fact and fiction are to be rewoven into truths of convenience—post-truths—then reality is secondary to its presentation.

Gail Skudera, Big and Little Women – Mountain Rose, 2014. Woven photo collage, 35 x 24." Courtesy of Maine Center for Contemporary Art.

Mainers are accustomed to art and politics intermingling into caustic post-truths. In 2011, Maine Governor Paul LePage ordered a mural depicting Maine workers removed from the State House after receiving an anonymous fax asserting that the mural was “nothing but propaganda…to brainwash the masses.” LePage, an extreme right-wing politician elected in 2010, recently made news for asserting that Democratic Senator John Lewis needed a “history lesson,” and has had, to put it mildly, a fraught relationship with the NAACP. LePage’s tenure in Maine is in many ways a harbinger of President Trump’s election; the governor heralded the xenophobic Nationalism sweeping the United States, Great Britain, Turkey, and other countries. These movements are predicated on post-truth and a refusal of factual observation and operate through the refraction of perception through fear. This is the denial of empathy, and it’s what fuels politicians like LePage. As Judd wrote in 1975, “if the local control is more than practical it becomes dangerous, becomes mysterious and moral and overwhelming, like the present governments.”[i]

Kathy Weinberg’s twenty-six trompe l'oeil tile paintings at the Biennial’s conclusion subtly deal with the complication of observation and perception into post-truth. All are vignettes of figures looking or seeing, enlarged or reduced, each tucked closely together as a piece of the larger whole. Executed in a wispy stroke, these aren’t complicated pictorially. But they concoct an assessment of our fractured present, when seeing isn’t believing, belief is what you see.

Kathy Weinberg, Antares, 2015. Acrylic on wood panel, 24 x 24." Courtesy of Maine Center for Contemporary Art.

The Center for Maine Contemporary Art's Biennial is open through February 5, 2017.

[i] Donald Judd, “Imperialism, Nationalism and Regionalism.” Donald Judd: Complete Writings 1959-1975. Judd Foundation: 2016, 222.

[i] Judd, 222.