The anniversary exhibition First Light: A Decade of Collecting at the ICA is composed of four small shows that are individually arranged by the Museum’s curators. Partway through the exhibit’s run, two of these and one of the video installations were switched. (For a review of the first installation, click here).

Freedom of Information, arranged by Curatorial Assistant Jeffrey De Blois, replaced Question Your Teaspoons, curated by Assistant Curator Ruth Erickson. Rineke Dijkstra/Nan Goldin, organized by Curatorial Assistant Jessica Hong, was replaced by Louise Bourgeois, another Erickson show. Ragnar Kjartansson’s video The Man was also added, replacing Sharon Hayes’s Ricerche: three. Soft Power, The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women, and Paul Chan’s video First Light have remained throughout the exhibition’s entire run.

Freedom of Information focuses on how artists appropriate other media, including other artists’ works, in their creations. Artists cut, tear, splice, glue, and otherwise reinvent found objects to create their own work. Most of the works are prints, drawings, or photographs; two televisions (from Dara Birnbaum’s work, discussed below) are the only objects that occupy any floor space, which is surprising since sculpture is a significant portion of the collection.

Klara Lidén’s Untitled (Poster Painting), for instance, is composed of many layers of advertisements taken from public walls. The posters’ messages are layered on top of each other with the top sheet painted opaque white, thereby obliterating their transactional messages. By carefully offsetting the posters from each other and curling a few edges away from those below, the origin and nature of the posters are revealed.

Using found materials is an efficient way to examine society with a more accessible visual language. In Kiss the Girls: Make Them Cry, Dara Birnbaum exposes how deeply ingrained and gendered body language is by playing clips of game show contestants with all sound and speech replaced by the titular “Georgie Porgie” song. Carol Bove’s Innerspace Bullshit presents a shelf of found ephemera ranging from print materials to a small rock. It can be read as a shrine to a previous time in her life, evidence to investigate her past, or a way of constructing a memory.

When using found objects, we are confronted with heady questions: who is the artist, and where is the art? Sky Blue World, from the 25 Worlds Series by Gilbert and George is a collage of three postcards repeated in concentric rectangles. The postcards are of an actor, a backlit skyline view of religious architecture, and an intricate representation of a seascape. Do we consider the person who took the photos on the postcards an artist? The postcards’ subjects are different forms of art. Can we consider representations of art to be art themselves? Does the appropriation of these images by Gilbert and George sever these other connections and turn the postcards into something distinct from their original form, specifically a Gilbert and George artwork?

Questions of authorship, authenticity, and originality are important topics in contemporary art, and ones that the ICA has posed in several of its recent exhibitions such as Geoffrey Farmer and Walid Raad. Concurrently, the ICA’s show Artist’s Museum, which debuted a few weeks after Freedom of Information, invites artists to shift from the role of creator to curator. The Museum asked artists to curate their own selections of found artworks to make miniature museums that focus on cultural phenomena and constructed narratives, among other topics. Carol Bove, Louise Lawler, and Sara VanDerBeek all make an appearance in both Freedom of Information and Artist’s Museum, so visitors can continue to investigate the artists’ relationships to making and presenting artwork.

It seems that the ICA will continue to invite this discussion with installation artist Mark Dion’s exhibition this fall. Dion creates rooms of found objects, usually more scientifically focused, that resemble offices or storage facilities.[i] Dion invites us to imagine who made these spaces, why they collected these particular items, and what their motivations were for arranging them as they have–in a sense, to question curation, authorship, and context.

While Freedom of Information focuses on larger concepts of originality and appropriation, its neighboring Louise Bourgeois pulls visitors into the artist’s world of uncannily lifelike and abstracted forms. I found it refreshing to look at contemporary art that was not referencing other contemporary art. There are five artworks on display in this show, and Erickson uses them to give us an impressively thorough overview of Bourgeois’s decades-long career. Upon entering, the visitor is greeted with two sculptures from the artist’s Janus series. These lobed basketball-sized objects, made of porcelain and bronze, hang at eye-level and spin slowly of their own accord. The forms are soft and organic, their movements alternating between benign and eerie. The Janus sculptures are the earliest of Bourgeois’s work represented in this show and demonstrate the artist’s longtime interest in exploring the spaces between animate and static, abstract and representational, and organic and fabricated. Untitled, the only drawing by Bourgeois in this show, is a wonderful neighbor for the Janus sculptures, depicting similarly lifelike yet unidentifiable forms.

Arched Figure No. 1 is a wood and glass vitrine that houses an arched body made of chicken wire, covered in pantyhose, and embellished with cartoonish breasts, a vulva, and a butt made of stuffed cloth that all protrude from the sculpture’s body. The cloth is so tautly stretched over the chicken wire that I expected to see a run appear at any second. I could imagine it emitting a scream of agony just as easily as a sigh of contentment.

Louise Bourgeois, Cell (Hands and Mirror), 1995, marble, metal, and mirror, 63 x 48 x 45 inches (160 x 121.9 x 114.3 cm). Gift of Barbara Lee, The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women Charles Mayer Photography. © 2016 The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

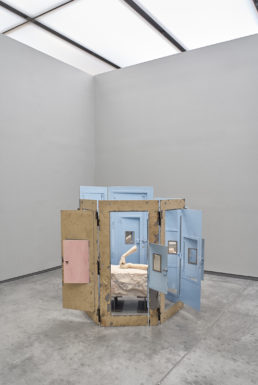

The sculpture Cell (Hands and Mirrors) is in the center of the gallery. It consists of a series of panels with doors that allow us to peer inside at mirrors that reveal different angles. There, two hands and their associated forearms are entwined in an embrace. It is unclear if the hands belong to the same person or separate individuals. The hands could be clasped in a warm caress or a snarled moment of violence or confusion. Looking feels intrusive, like barging into a private display of affection or anger and then sticking around to see the show.

The current Bourgeois show is much smaller than the ICA’s previous survey of her works but meticulously crafted. Each work dominates its own section of the gallery. Yet the lifelike forms play well together to give a brilliant glimpse of the artist’s work. Fortunately, the visitor can see more of Bourgeois in The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women, just a few galleries over.

Directly next door to Louise Bourgeois is Ragnar Kjartansson’s video The Man. Kjartansson’s previous two shows at the ICA were well received by critics and visitors alike. His works are long, immersive, and intense. The Man is no exception to this. It was tricky to acclimate to The Man after the Bourgeois gallery, and hearing the video’s music in Louise Bourgeois detracted from the otherworldliness of her work. Furthermore, its sound bled into another video work in Freedom of Information. One could not be heard without the other. Adding Kjartansson’s work despite the limited space in the galleries of First Light seems to indicate how important the ICA feels Kjartansson is in telling the Museum’s own story. I appreciated his inclusion but thought the execution was a bit clumsy.

Ragnar Kjartansson, The Man, 2010, single-channel video (color, sound; 49:00 minutes). Gift of Graham and Ann Gund to The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and Gund Gallery at Kenyon College. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and i8 Gallery, Reykjavík © 2016 Ragnar Kjartansson

The six inner shows and three video works that have composed First Light throughout its run have allowed the ICA to share its values and history with visitors. There have been many works, artists, exhibitions, and people who have been vital to the ICA’s history–Fiber: Sculpture 1960 - Present, Cornelia Parker’s Hanging Fire (Suspected Arson), and donor Barbara Lee, to name a few examples.

The collection is young, but First Light gives us insight into how the ICA is growing. Some of the collection’s works are incredibly strong, but more require insightful and compelling curation to be able to match the heft of these stronger works.

First Light shows the ICA’s importance as a learning tool for the Boston community. It wants to make visitors think about what a museum is, and how museums can influence the artwork they show. The ICA has given itself a strong foundation to continue seeking out voices and stories that have been largely ignored in the greater museum world, and inviting visitors to actively reflect on how the Museum is shaping the telling of those stories.

[i] Robin Cembalest, “The Curator Vanishes: Period Room as Crime Scene,” ARTnews, February 28, 2013, http://www.artnews.com/2013/02/28/mark-dion-curator-office-in-minneapolis/.